On Tuesday 26 June, 15 Masters in policy and governance students from the University of Canterbury visited the Institute to talk to Wendy about her work in politics, governance and policy. The students were curious and engaged and had prepared a list of questions for Wendy prior to the meeting:

What is your framework for employing hindsight, insight and foresight?

Looking at the current project LivestockNZ, how much of an influence do you foresee public pressure having on your policy decisions regarding ethical treatment of livestock?

What do you think about the conflict between the goals of the McGuinness Institute – a long-term think tank (project 2058) and the goals of whatever party is in office – a relatively self-interested group looking forward 3 or 6 years?

Can you tell us something surprising or exciting about the McGuinness Institute that is not necessarily online?

Do you offer a graduate program?

What does your average day consist of?

If there was one piece of advice you could give us what would that be?

What do you see as the most challenging part of your job?

Do you have any tips for a student going into politics?

What is the most important personality trait for working in policy research?/What skills and experiences would make an ideal employee in the McGuinness Institute?

What do you think people like the most about working on policy research?

Unfortunately, time was limited due to the students’ later meetings with MPs at Parliament and Wendy was not able to answer all the questions. However, the discussion did cover a number of points including some more general information about the Institute and some extra tidbits from Wendy’s personal experiences working in the policy area.

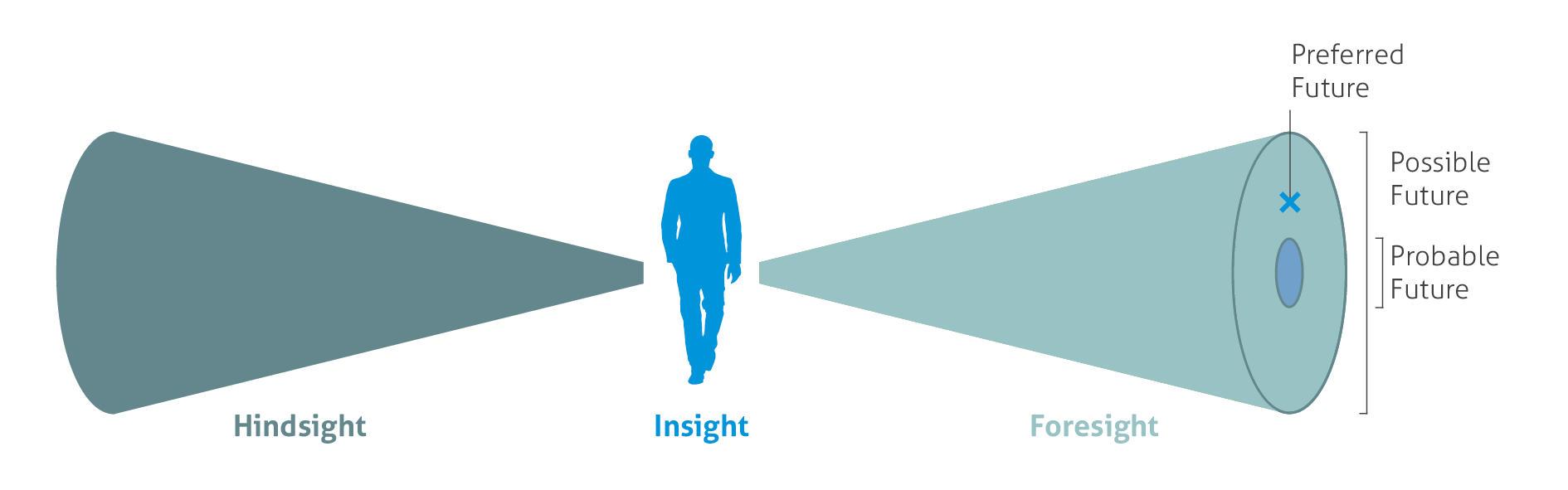

Regarding the Institute, Wendy discussed funding structures and asserted that the students should always be able to understand where the money comes from and what the relationships and obligations are surrounding that. She went on to explain the Cones of plausibility, possible and preferred futures, and their relevance to Project 2058.

Cones of Plausibility

This linked into discussion of why the Institute uses the framework of hindsight, insight and foresight. The framework builds on the cones of plausibility and the importance of acknowledging different perspectives of history and arose from Wendy’s attempt to understand the shared goals of Māori. Wendy’s broader interest in understanding patterns then came to fruition in Nation Dates. Wendy shared Mark Twain’s quote from the preface of the book that ‘history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme’.

University of Canterbury Masters students at a later meeting with DPMC

Wendy went on to share some of her own wisdom and advice:

- Reading is very important as it how people make sense of their ideas. However, it can be hard to find the time. Some books need to be read all the way through, but some books tell you everything you need to know in the contents page, and the first and last chapters.

- If you are taking on the role of an MP or policy analyst, be kind and be curious.

- Say to people ‘I am going to do this, do you want to come and join me?’.

- The most challenging part of the job is juggling areas of interest.

- Some people are ‘back room’ people and some people are ‘front room’ people. If you are a back room person who finds yourself wanting to influence people, remind yourself that the topic is more important than the messenger.

- Making sense of the mess is the most enjoyable part of working on policy research.

Wendy also shared some the important personality traits she looks for in employees of the Institute:

- curious

- creative

- hardworking

- kind

- exacting

- can see the bigger picture

- strong values (people who want to make the world a better place)

She shared a reassuring observation from Sam Morgan that the peg and the hole need to fit each other – neither a square peg nor a round hole are necessarily wrong. Sometimes it can take a long time to find the right fit, so enjoy the process: we learn more about a system through what does not work than what does.