I attended the Global Macroeconomics Issues course at the London School of Economics from 11 to 15 June 2018. The teaching faculty included Gianluca Benigno (Associate Professor), Paul De Grauwe (Professor), Lorenzo Codogno (Professor), Linda Yueh (Adjunct Professor) and Brunello Rosa (Founder of Rosa & Roubini). There were ten participants from around the world. Below are my personal notes and observations rewritten with a public policy focus. Speech marks indicate extracts from the lecturers’ slides.

Five topics were covered over the five days:

- Issues on a Monetary Union

- The Mystery of Missing Inflation

- Macroeconomic Challenges of Global Imbalances

- The EU Fiscal Framework and its Evolution

- China: Emerging Superpower

Key course takeaways were:

- The study of economics cannot be separated from the study of politics, with the March 2018 Italian election being a case in point.

- The Economic and Monetary Union of the EU (EMU) cannot remain as is; its current position of being half-in/half-out of a full union puts the member countries at risk in turbulent times. With Britain leaving the EU, a full union seems either fully viable or impossible, depending on your viewpoint. What is clear is that many speakers did not think the status quo will, or should, remain.

- The EU was possibly set up wrong and over time this has undermined the financial wellbeing of some member states (e.g. Greece and then Italy).

- Both participants and speakers recognise that this might be an important time in history.

Issues on a Monetary Union by Paul De Grauwe

‘Banking Union is the key in resolving the deadly embrace between sovereign[s] and banks’.

Background

- There are currently 28 full members of the EU (including Britain). See full list.

- There are 19 countries that belong to the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), these countries are collectively known as the Eurozone: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Two opted out – England and Denmark.

- There are 7 countries still to join the Eurozone (they can no longer opt out). These countries are: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden.

- Paul De Grauwe spent a day with us explaining the issues that he considers are currently before those countries that are members of the EMU. Although not directly relevant to New Zealand, it was a very interesting session.

- De Grauwe put forward the view that the current status of the EMU is fragile as it ‘failed to take into account the dynamics of booms and busts, and the fragility of an incomplete monetary union’.

- He notes that the European Central Bank’s (ECB) ‘power has increased significantly as a result of the sovereign debt crisis, but unlike other banks, like the Bank of England, Governments have no power over the ECB and cannot force that institution, even in times of crisis, to provide liquidity’. Further, ‘the ECB consists of unelected officials, while governments are populated by elected officials’. ‘It is unconceivable that these governments will accept to be pushed into insolvency while unelected officials in Frankfurt have the power to prevent this but refuse to use their power.’

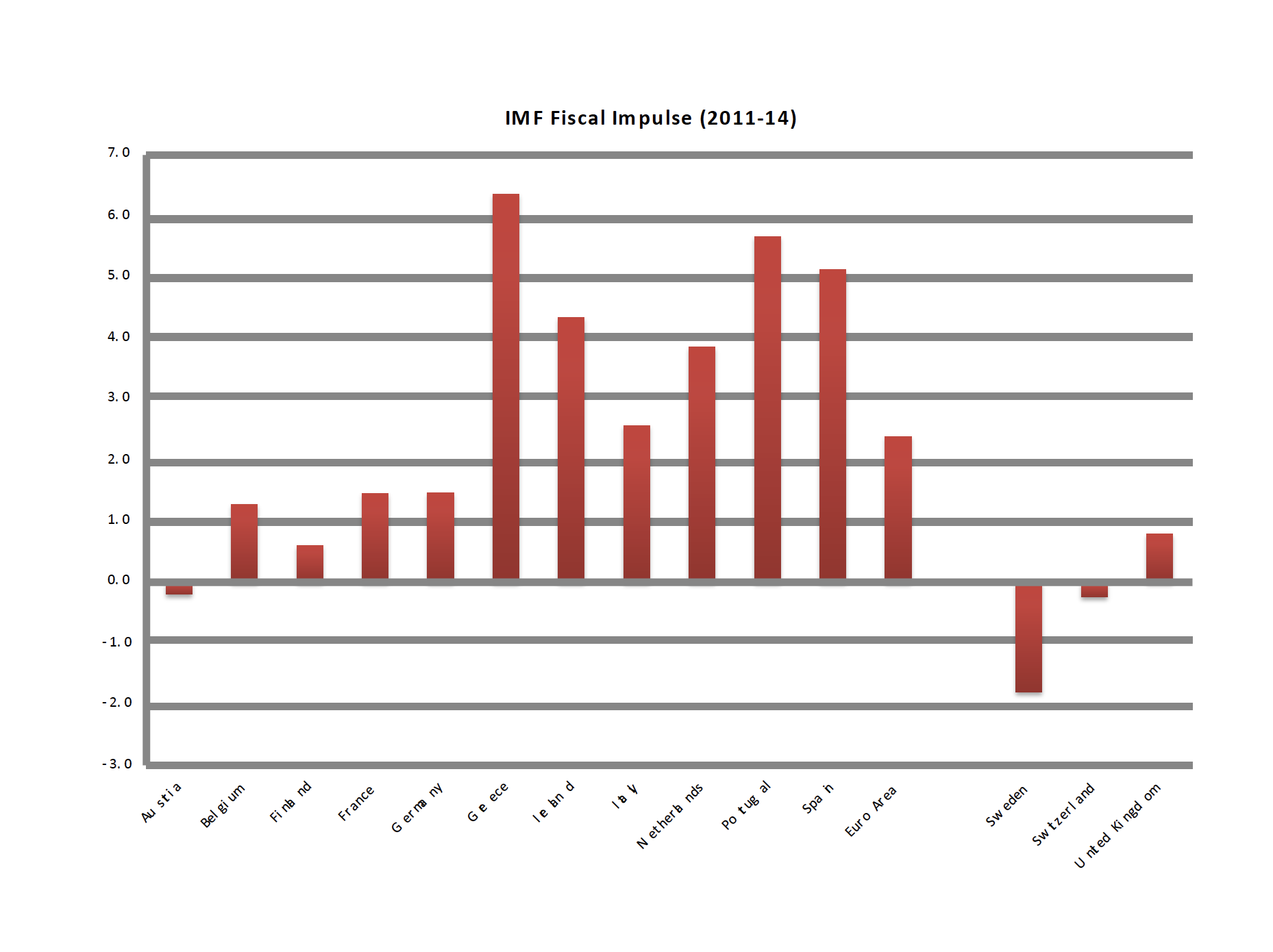

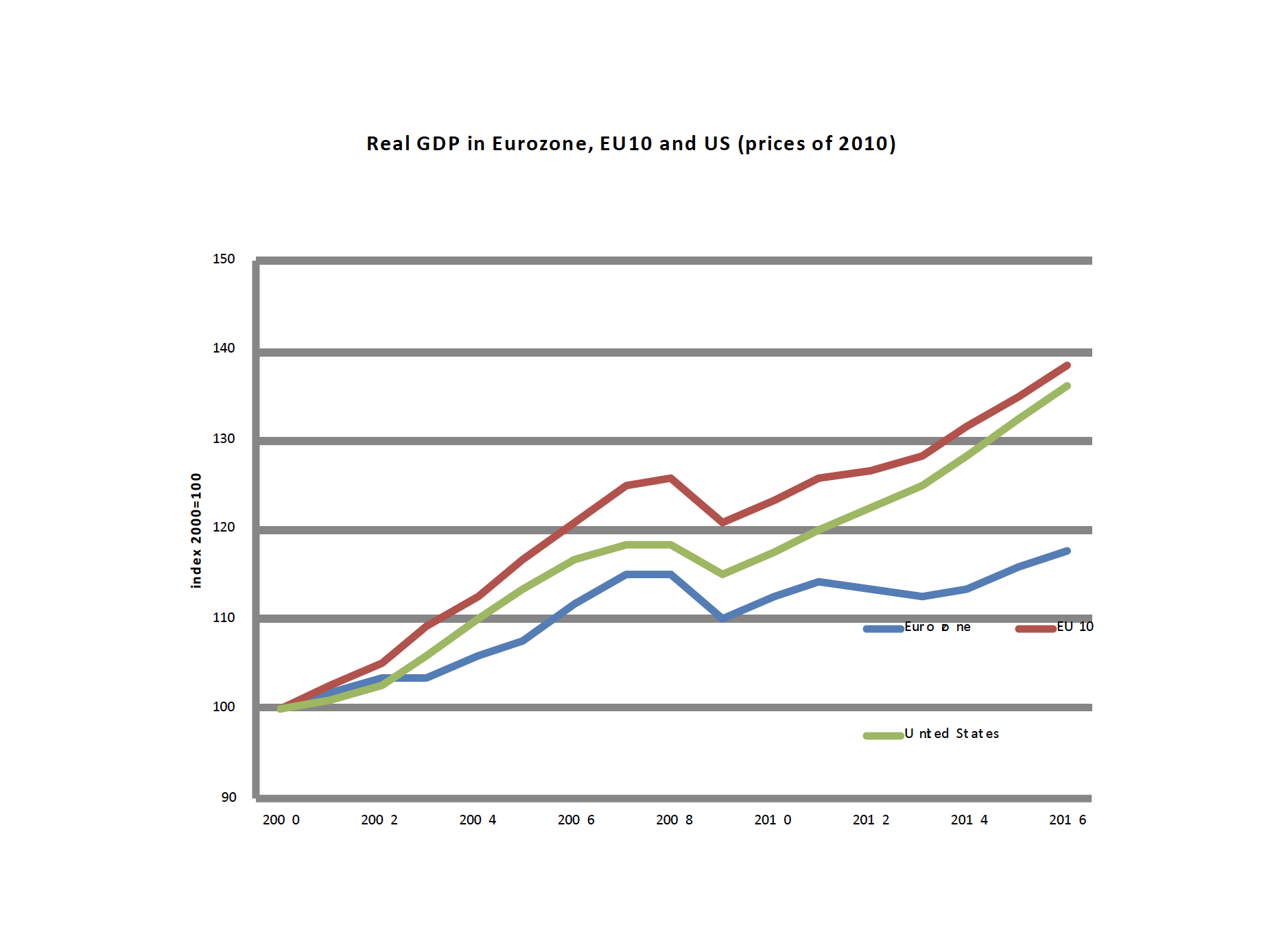

- He argued that during the sovereign debt crisis of 2010–12, the wrong diagnosis was made and therefore the wrong medicine was administered – ‘excessive austerity in periphery without fiscal stimulus at the center’. This resulted in a much slower recovery in the Eurozone.

Executive course, p. 9

Executive course, p. 10

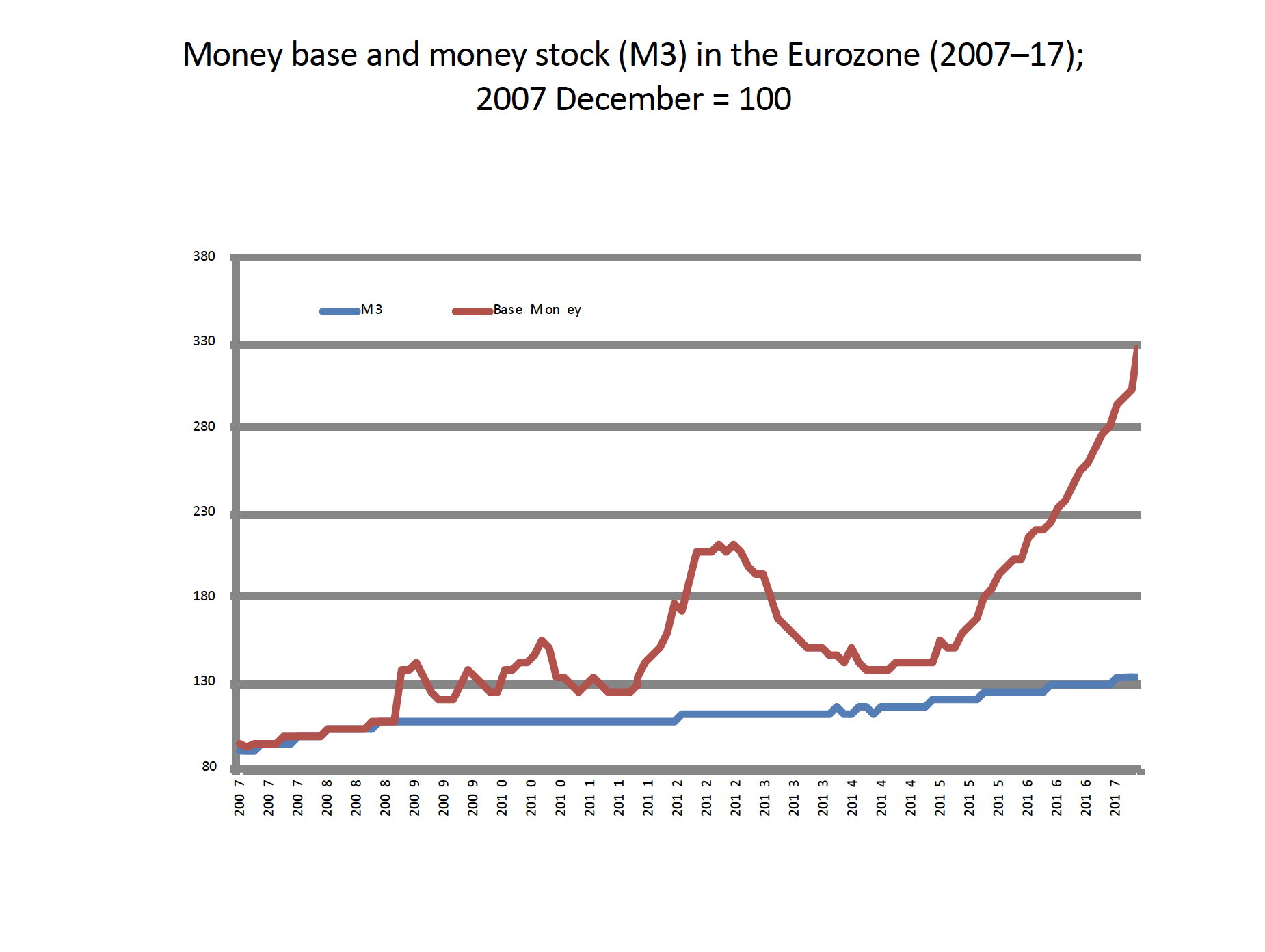

- On 6 September 2012 ‘ECB announced it [would] buy unlimited amounts of government bonds’; ‘this was the right step’. ‘When central bank provides liquidity as a lender of last resort “money base” and “money stock” move in different direction[s]’. This is because ‘in general when debt crisis erupts, investors want to be liquid’. The money base is the total amount of a currency that is either in general circulation or held in commercial bank deposits in the central bank’s reserves and the money stock is the total value of monetary assets available in an economy.

Executive course, p. 18

- De Grauwe concluded that ‘political unification is needed because Eurozone has dramatically weakened the power and legitimacy of nation states without creating a nation at the European level’. Hence the EMU needs to either become a full union (including central budgeting) or revert to the previous system.

- De Grauwe noted that the ‘willingness today to move in the direction of a budgetary union in Europe is non-existent’. A budgetary union has two dimensions: ‘consolidation of national government debts’ and an ‘insurance mechanism … transferring resources to the country hit by a negative shock’.

- There were some lessons for New Zealand:

- The central bank’s objective should be financial stability, not making profits.

- Nation states need to have access to both monetary policy (actions of a central bank that change the supply of money) and fiscal policy (actions taken to change expenditure or revenue [e.g. taxes] to influence the economy) in times of crisis.

- There are two types of asymmetric shocks (economic events that affect one economy or part of an economy more than another):

- Exogenous asymmetric shocks, which are permanent shocks that occur outside the model (e.g. like productivity shocks or supply shocks).

- Endogenous asymmetric shocks, which are temporary shocks that occur inside the model as a result of business cycle movements. The discussion on the effect of ‘animal spirits’ (a term used to describe the psychological factors that drive the behaviour of investors when capital markets are volatile) was fascinating. This is why maintaining confidence is so important.

The Mystery of Missing Inflation by Brunello Rosa

- Economists often talk in terms of puzzles or mysteries and missing inflation is no exception. The mystery of missing inflation refers to an increase in growth without a corresponding increase in inflation. Economists do not really understand why this gap currently exists and whether this gap is permanent or temporary.

- If you want to learn more about the mystery of missing inflation, I recommend reading Rosa & Roubini’s 2017 paper (see My broad understanding of the issue before economists is whether to treat missing inflation as permanent or temporary. If permanent, many economists would advise the central bank to react and ease monetary supply, conversely if temporary, they should not react, ‘as eventually the temporary supply shocks will wear off and inflation will get higher’ (Rosa & Roubini, 2017, p. 6). Inflation could be imported through technological advances, globalisation and/or commodities (such as metal or oil), but Rosa believes that domestic and imported inflation is ‘likely to remain subdued’. Hence global inflation is likely to remain subdued, although markets will ‘still be vulnerable to inflation scares’.

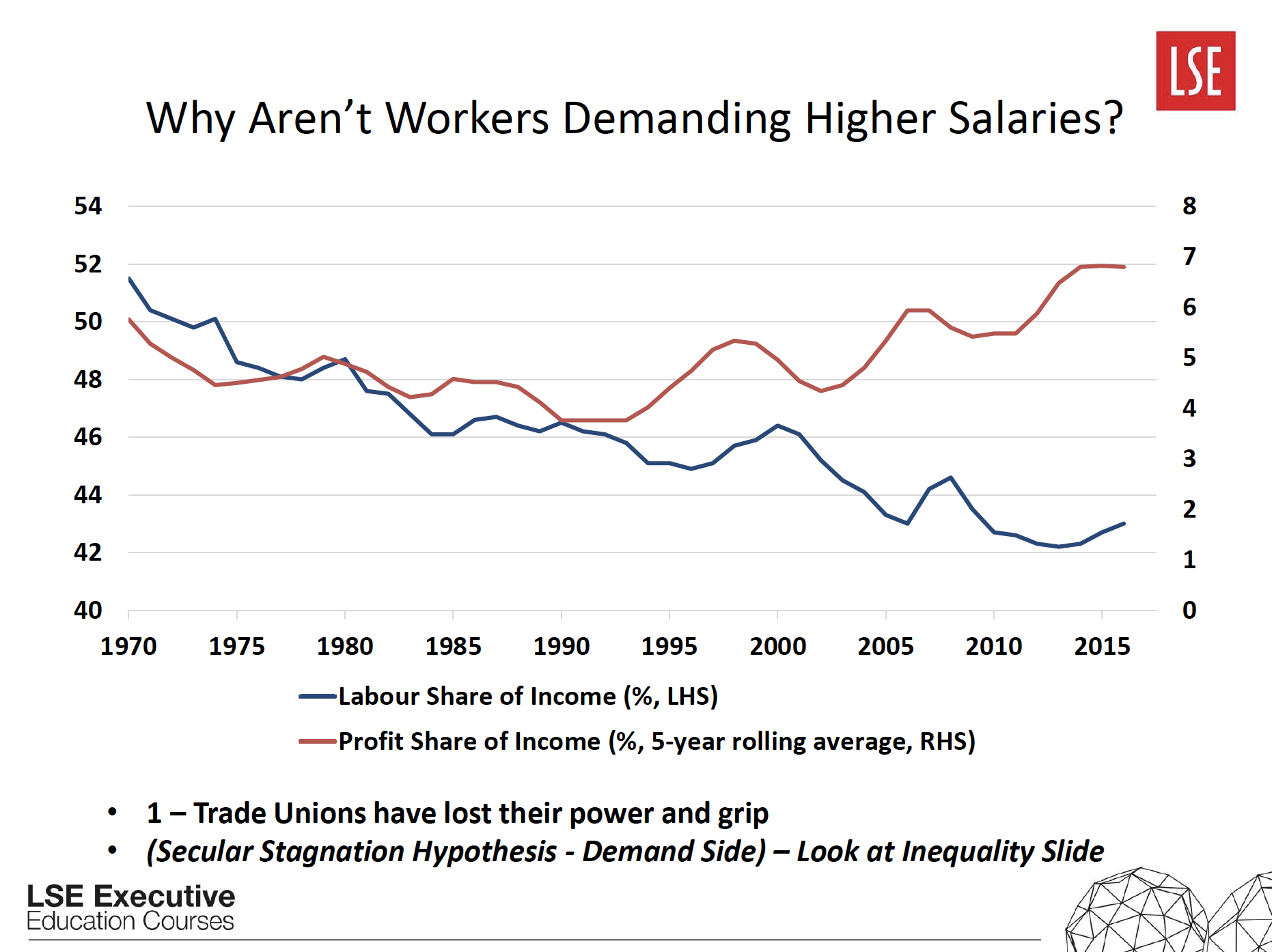

- I was surprised by the below graph. Using US data, it shows ‘the labour share of income’ has decreased and ‘the profit share’ has increased from 1970 to 2015. The paper notes ‘because of this decline in the labour share of income, unions have lost a lot of bargaining power (at most they can ask for companies not to be related abroad) and – conversely – given the loss of influence by the unions, the rate of increase of labour remuneration remains subdued’ (p. 6). I am unsure whether there is a New Zealand equivalent of this graph, I did come across the following in a Productivity Commission research note The Labour Income Share in New Zealand: An Update, found here, ‘this note is the starting point of a conversation around the labour income share and inequality’, suggesting that such data may be forthcoming (Fraser, 2018, p. 10).

Brunello, p. 16

Macroeconomic Challenges of Global Imbalances by Gianluca Benigno

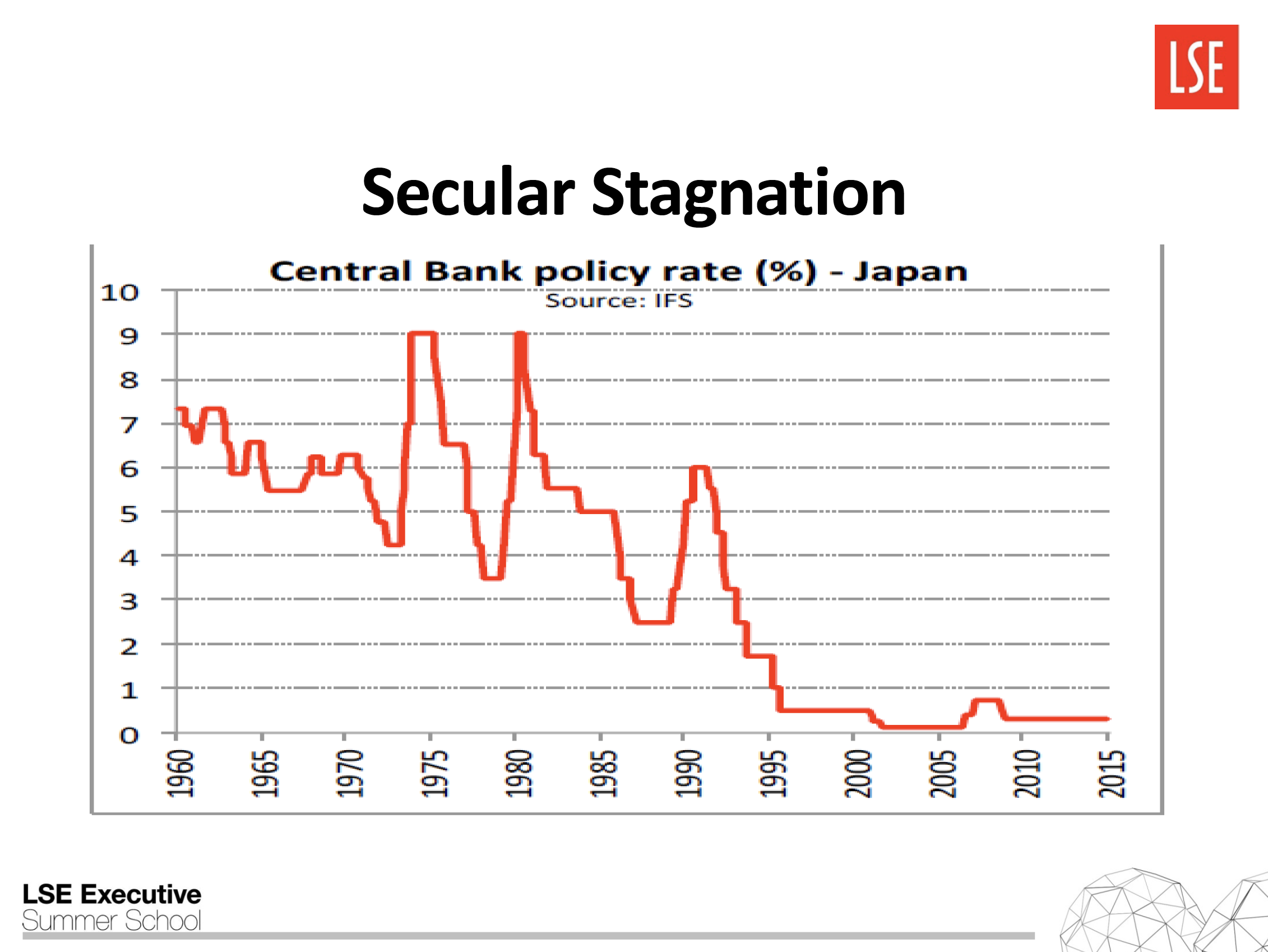

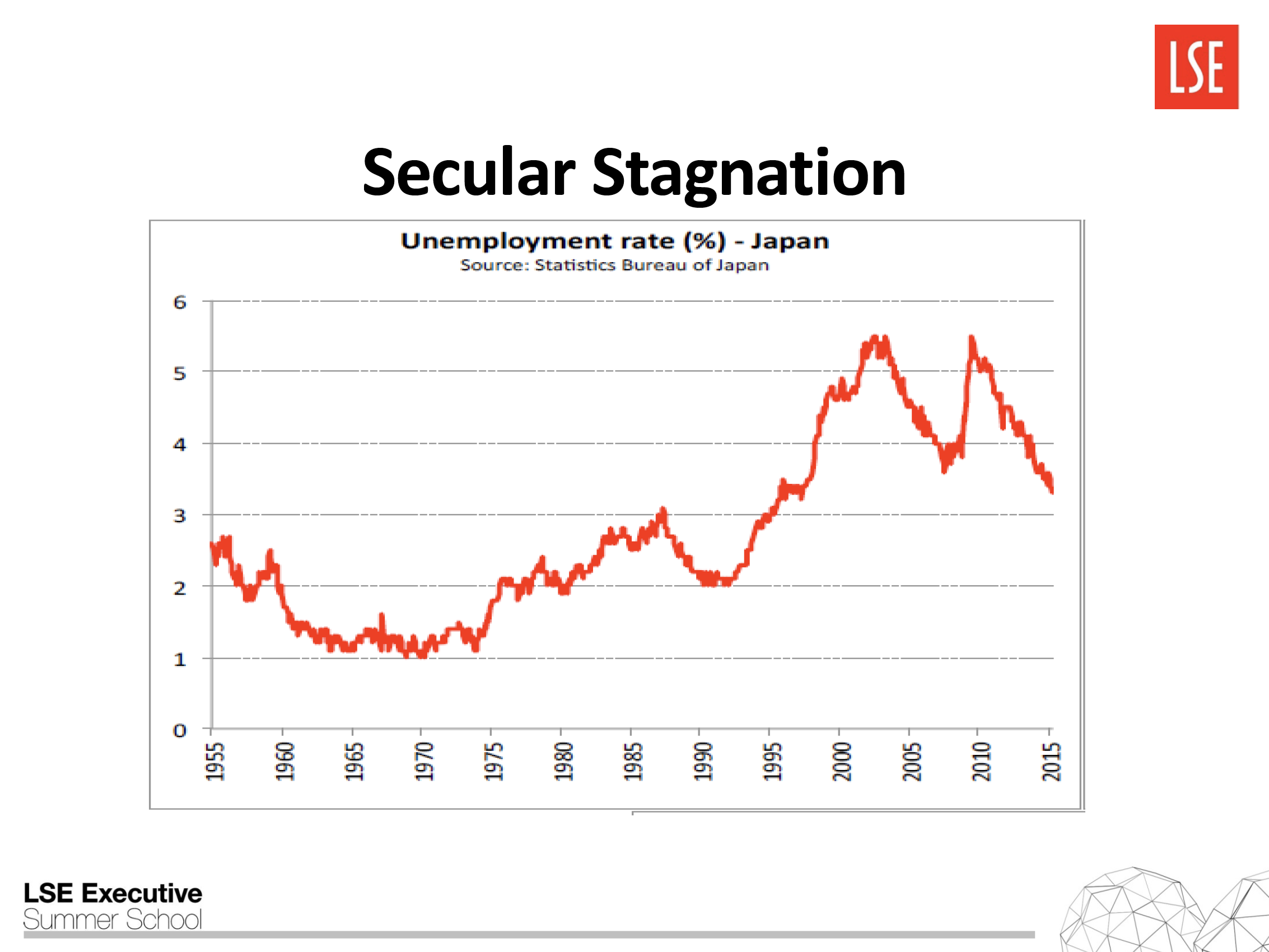

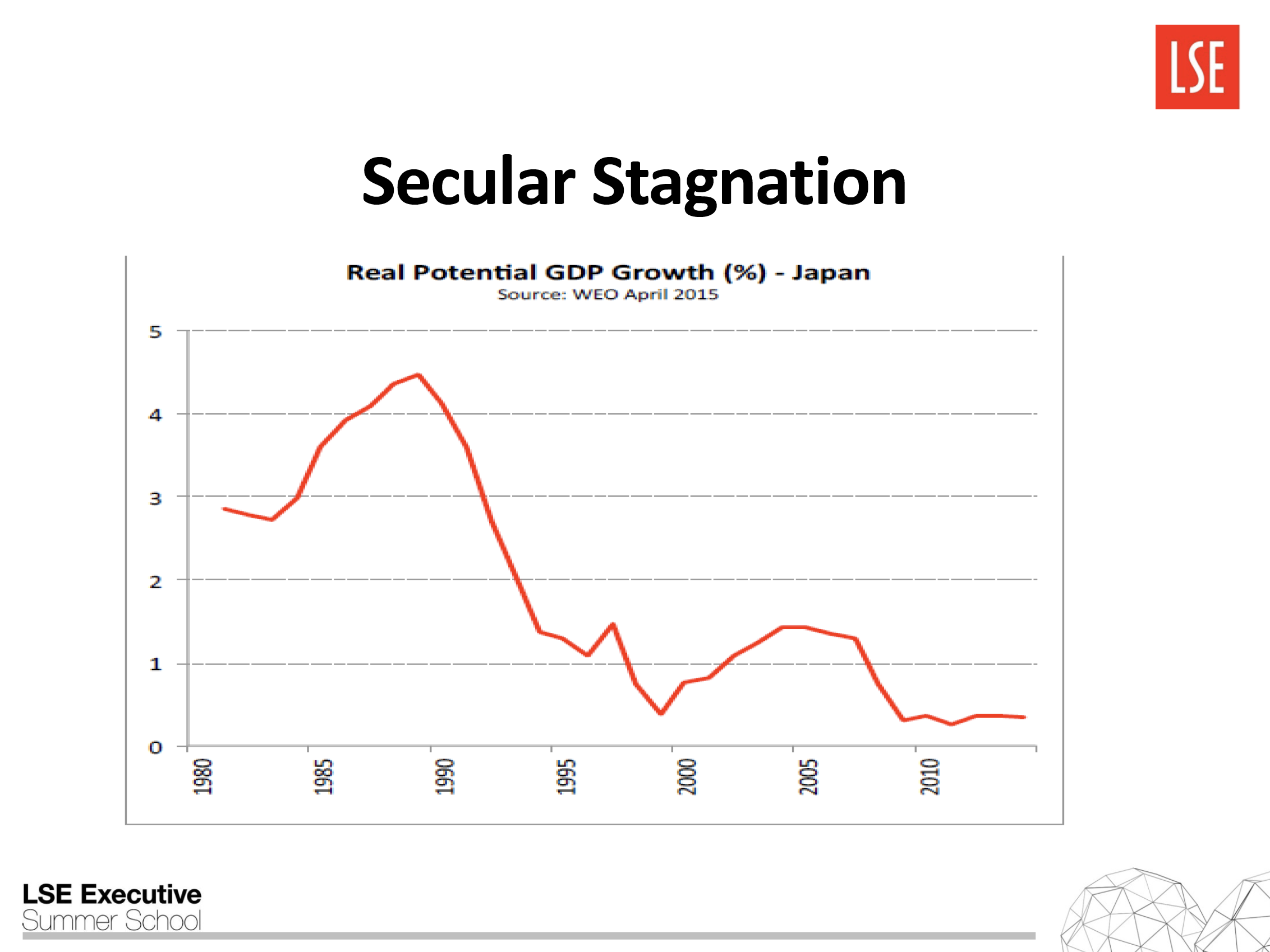

- Although Benigno discussed many challenges, the one that resonated most was the challenge of secular stagnation. Key features of secular stagnation include a ‘period of protracted low growth’, a ‘period in which nominal interest rates are the zero lower bound’, ‘low inflationary pressures (deflation at times)’ and a period when ‘real or low interest rates are low or negative’.

- Japan’s economy offers an example of secular stagnation, as illustrated by the three slides below.

GB Global, p. 19

GB Global, p. 20

GB Global, p. 21

- There is concern that secular stagnation may turn into a global issue.

- In terms of the supply-side perspective, Benigno discussed four structural ‘headwinds’: stagnant population with increased life expectancy, education (mass education is complete), inequality (no income growth for the middle class) and public debt (unsustainability of current social spending). How technology and these headwinds will influence growth are issues frequently debated by economists. This area of research is difficult; he referred to the American economist Barry Eichengreen who said ‘looking back in history predictions about [the] rate of invention and impact of invention have been systematically wrong’.

- In terms of the demand-side perspective, Benigno discussed four structural factors that may explain why real interest rates have declined: demographic and technological factors, lower price of capital goods, rising inequality with high income towards low propensity spenders and reserve accumulation and regulatory requirements.

- I was left with a feeling that we will hear more about secular stagnation going forward. His general conclusions echoed this:

‘Symptoms of secular stagnation are still present. Trump’s policies could be a shifting factor. Monetary policy environment points out at moderate normalisation. [[Joan not sure what this means and have sent him an email – thoughts?]] Risks in Europe coming from structural and political factors.’

The EU Fiscal Framework and its Evolution by Lorenzo Codogno

- Codogno set out the history of the EU Framework, which is a complex and integrated system.

- He then set out his understanding of the response to the global financial crisis (GFC), which he called the four legs of the crisis:

- The first leg of the crisis: contagion and GDP collapse

Sharp drop in export and investment activity, markets turmoil. In mid-2009, a tentative V-shape recovery led by a rebound in global trade and significant economic growth in emerging markets. - The second leg: Greece + banking/debt crisis in Europe

Increase in public debt, widening government bond spreads, interbank market closure, frantic policy reaction. - The third leg: Italy

Too big to fail, too big to be saved. Eventually, accommodative monetary policy and softer fiscal policy, but also debt overhang and fallouts of the balance sheet recession. - The fourth leg: Greece again

- The first leg of the crisis: contagion and GDP collapse

- Codogno explained there were many crises occurring at once:

- Exogenous shock: The trigger was the subprime crisis in the US, hitting through trade and financial markets contagion.

- Macroeconomic imbalances: Typical emerging market crisis, just within the Eurozone. Sudden stop of financial flows core/periphery.

- Banking crisis: Disintegration and fragmentation in financial markets, renationalisation of the banking industry.

- Public debt crisis: Existing weaknesses come to the fore.

- A monetary/fiscal policy response failure: Political/legal constraints, mistakes and delays, lack of interpretation model.

- Above all a governance failure: Political/institutional constraints.

- He then explained governance measures that have been put in place since 2010, in particular the six-pack and two-pack simplification of the rules and the Roadmap Towards a Complete Economic and Monetary Union (see Annex 1 of the Five Presidents’ Report Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union). Although not stated, my takeaway was that while changes made to date were moving the EU in the right direction, they will not be enough for the challenges ahead. More structural reforms are necessary to improve the institutional and regulatory framework in which businesses and people operate, so that the economy is better able to realise its growth potential and withstand shocks.

- Codogno then provided a detailed overview of ‘what next for Italy?’. He explained Italy was initially one of the most pro-EU countries, but is now one of the most sceptical. An article in The Telegraph on 4 June 2018 found here supports his observations and is worth a read: Italians fall out of love with the EU – but will they ever leave?. The recent coalition of two populist and Euro-sceptic parties – the Five Star Movement and the League – has added to the narrative that Italy may leave the EMU and possibly the EU.

- To conclude, the EMU is fragile, and it will cause less harm and loss for everyone involved to strengthen it rather than remove it. The status quo will lead to a crisis, and the question remains: ‘Can Europe withstand another crisis?’. The level of uncertainty over the EMU is creating anxiety for the EU and what is needed is a commitment to a clear plan outlining a way to a full union (such as political unity by 2048).

China: Emerging Superpower by Linda Yueh

- Yueh has published a book on the topic, China’s Growth: The Making of an Economic Superpower (2013), so I am not going to repeat her conclusions here. However, I did want to acknowledge the work China has undertaken to eradicate extreme poverty. As noted in Granma, the official voice of the Communist Party, China has already lifted 700,000,000 people out of poverty in less than 40 years and ‘the government’s current plan consists of lifting 10 million people a year out of poverty, while almost 14 million people saw their status change in 2016 alone’.

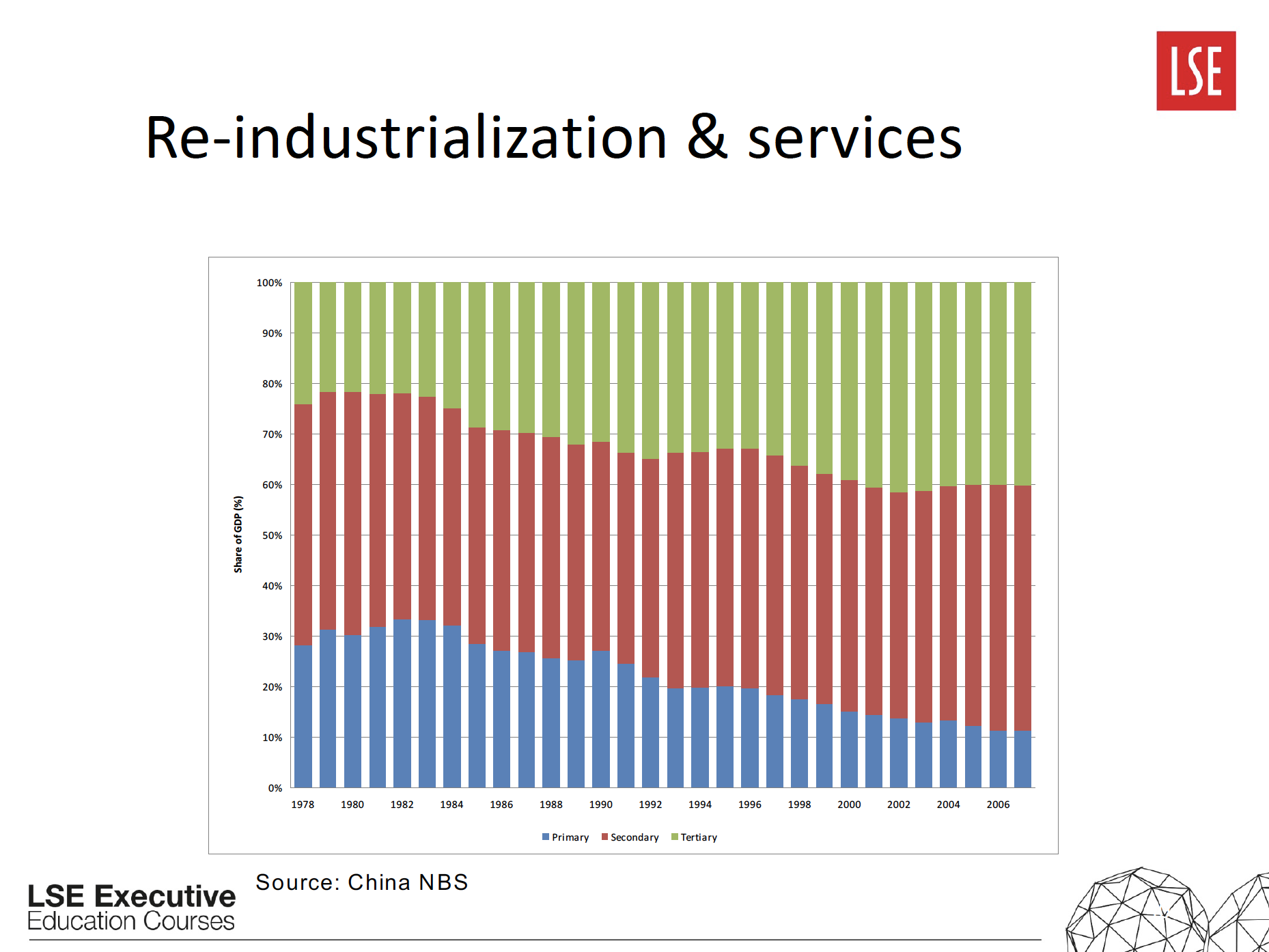

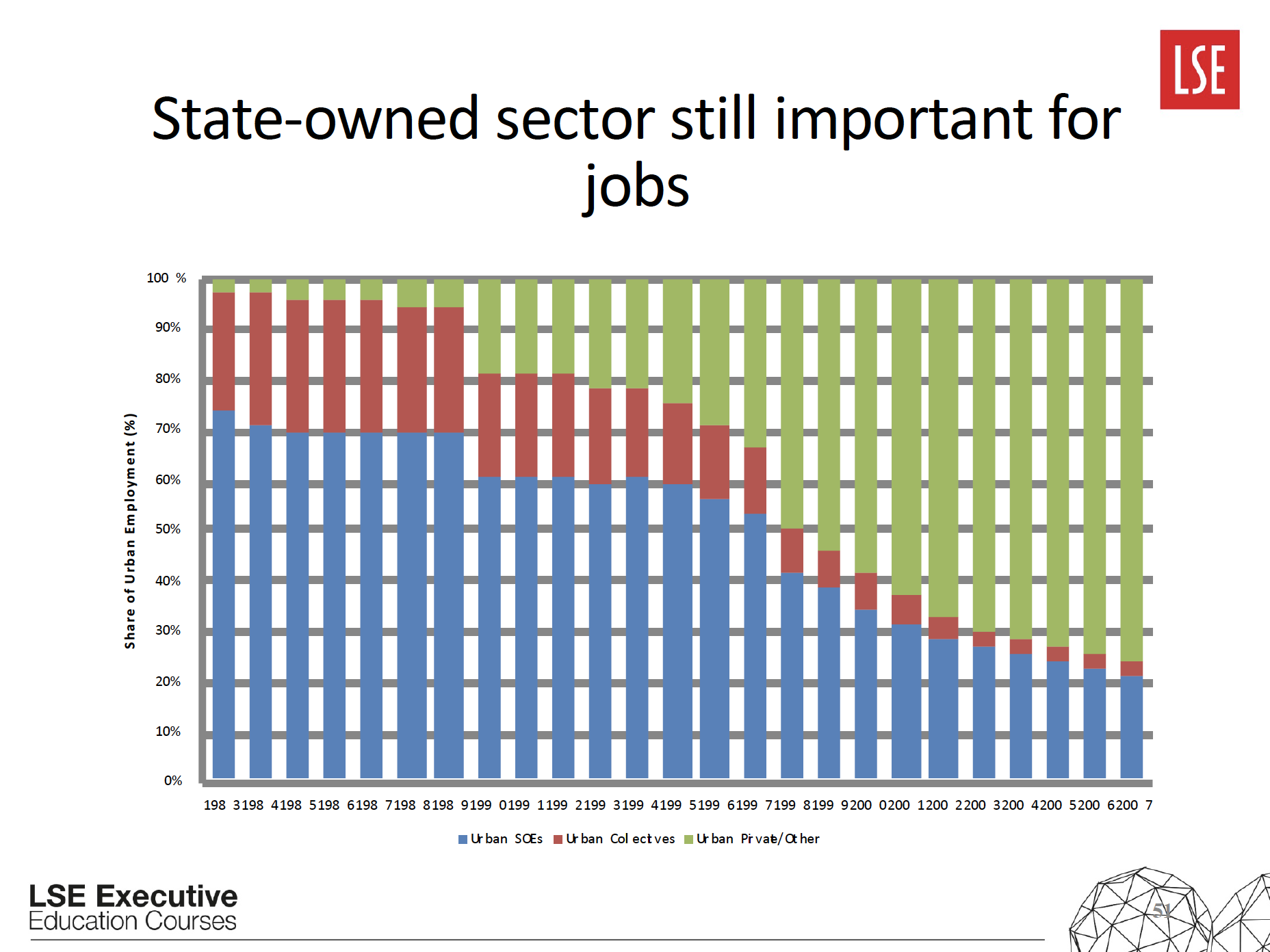

- The following two graphs are terribly old, but indicate the extent of the Chinese economy’s transition from the 1970s to the early 2000s.

Linda Yueh, p. 40

Linda Yueh, p. 51

- What interested me most about Yueh’s presentation was the discussion on the ‘middle income trap’. The trap refers to a theoretical situation where the economy of a country cannot move to a higher income situation because it has lost its competitive edge in the export of manufactured goods due to rising wages. Arguably, as the cost of labour increases (in the form of higher wages), manufacturing will move to where labour costs are cheaper, such as India or possibly North Korea. This means China needs to develop a new economy to create higher than normal wages. This point is not lost on China’s ruling party, which has emphasised innovation in its latest five-year-plan The 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of The People’s Republic of China (2016–2020), stating:

We will strive to make breakthroughs in making structural improvements, bolstering the drivers of growth, tackling problems, and strengthening areas of weakness; transform the growth model; improve the quality and efficiency of development; take care to avoid falling into the middle income trap; and constantly open up new horizons for development. (bold added)

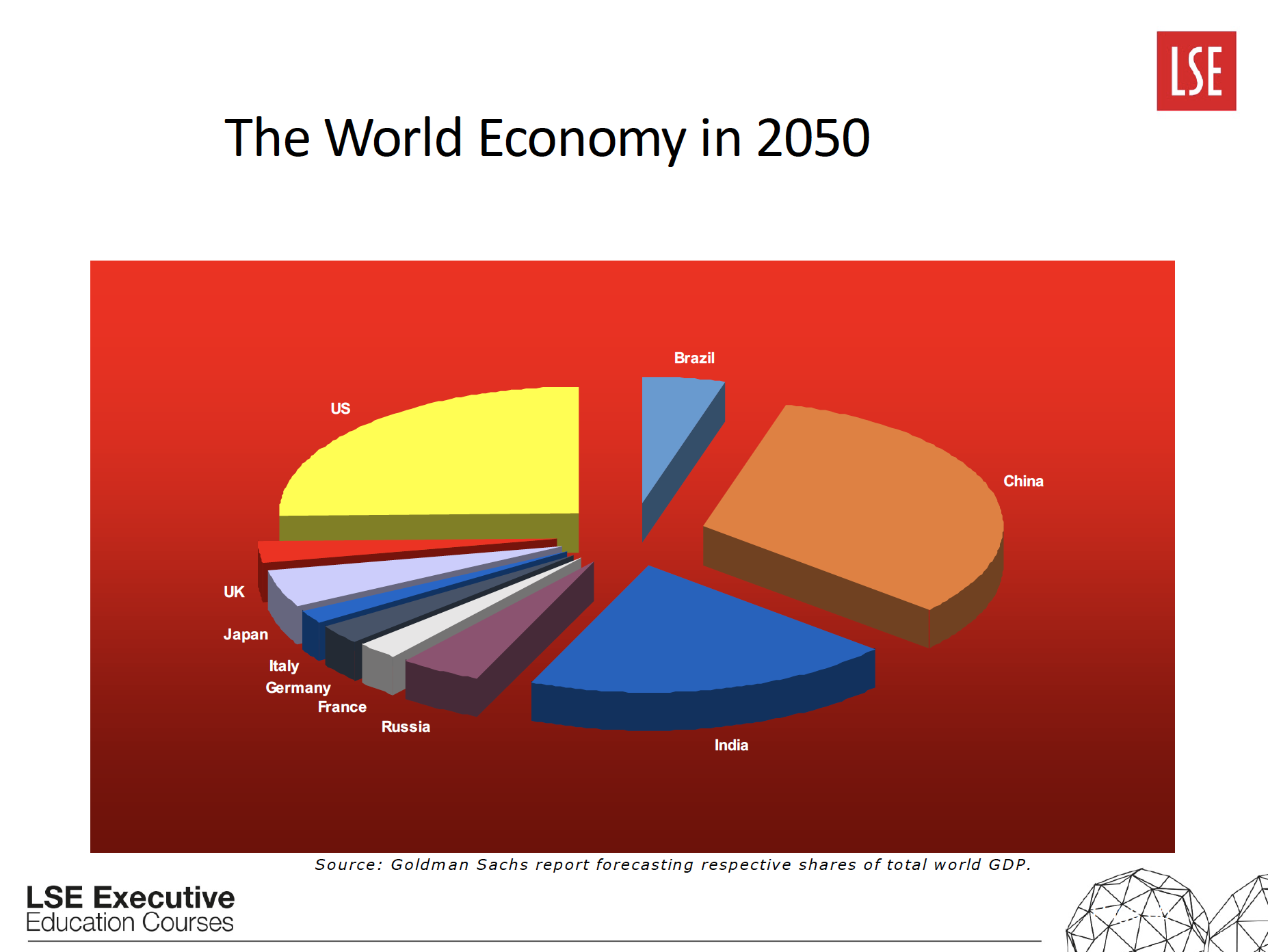

- The type of role China has in the world economy in the future will be an interesting development to watch.

Linda Yueh, p. 66

- To conclude, Goldman Sachs’ January 2018 Outlook report noted on p. 46:

China concerns: China remains a big source of uncertainty in the long run as a result of its growing debt burden. Capital controls, a stronger government hand in the economy and faster global growth have lowered near-term risks. There is also potential for a notable deterioration in the US-China relationship under the Trump administration driven by changing trade and foreign policy toward China.