I attended the Behavioural Economics and the Modern Economy course at the London School of Economics (LSE) from 11 to 15 June 2018. The teaching faculty included Matthew Levy (Assistant Professor), Nava Ashraf (Professor), Erik Eyster (Professor) and Dr Kristof Madarasz (Associate Professor). Behavioural economics is not a new area of research, but it is under-researched and therefore poorly understood. One of the speakers reinforced this by saying that his answer to many questions would be ‘it just depends’. There were 28 participants from around the world. Below are my personal notes and observations rewritten with a public policy focus. I have also added a small section on behavioural finance, though it was not my area of primary interest. Speech marks indicate phrases copied directly from the presentation slides. It was a terrific experience and I learnt a lot; I am looking forward to learning more as I incorporate this new knowledge into the work programme.

A new theory of choice

- Initially, economic theory proposed that size mattered most and that the way people will behave will depend on whether they believe the benefits of their actions will be large or small. This is known as the expected utility theory.

- Behavioural economists Kahneman and Tversky published a new theory of choice in a famous 1979 paper titled Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. As an alternative, ‘prospect theory’ explores the processes involved in the lead up to making a choice – what do people take into account and what are they influenced by when they make a choice. The theory suggests we make decisions based on how we value losses and gains rather than the final outcome. Kahneman and Tversky and others went on to explore a range of characteristics that influence decision-making such as current wealth, recent expectations, status quo and aspirations.

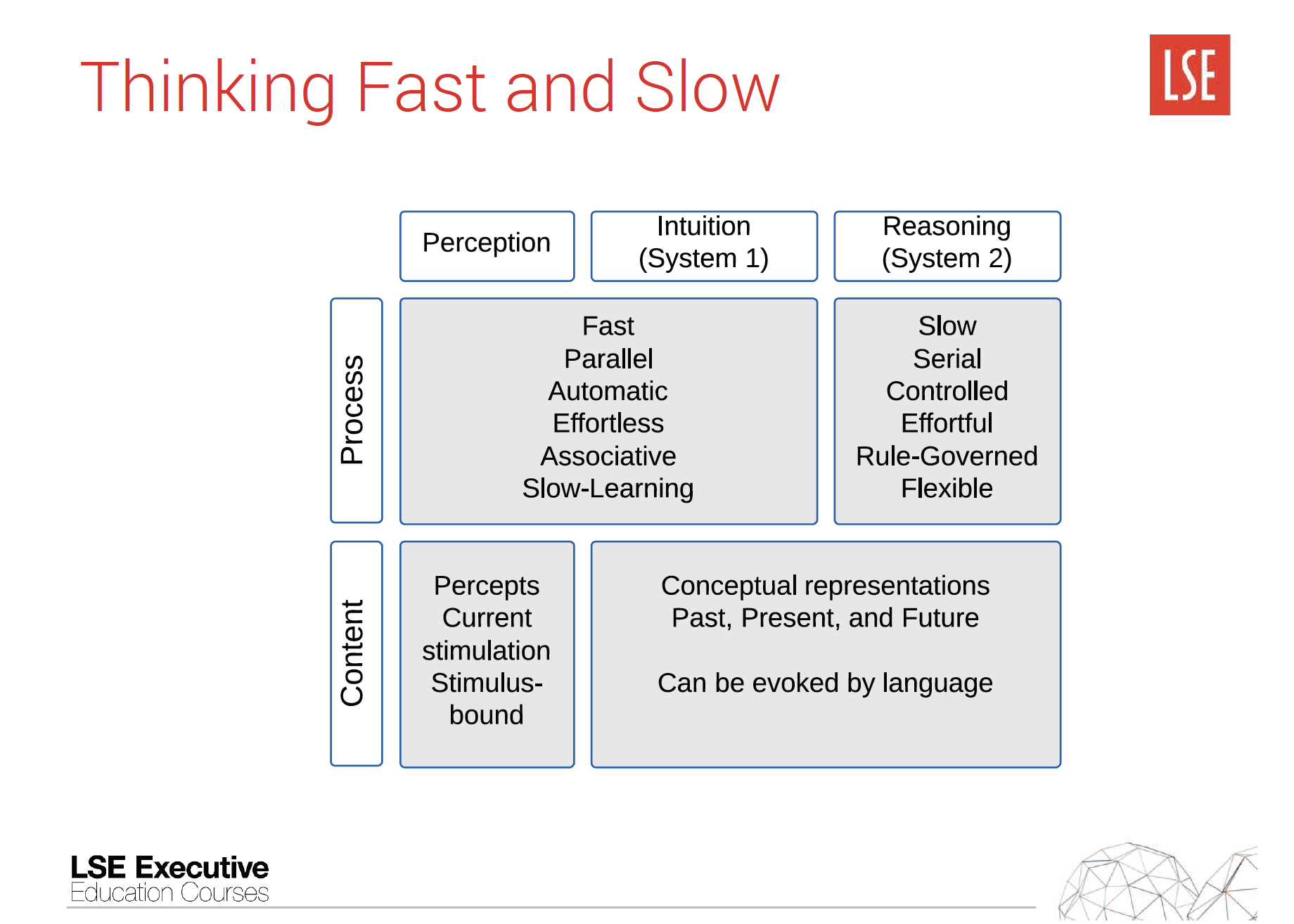

- Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow (2011), simplified the process of decision-making by redefining it in terms of system 1 and system 2 thinking. This is illustrated in the following slide.

Day 4, p. 2

Implications of prospect theory

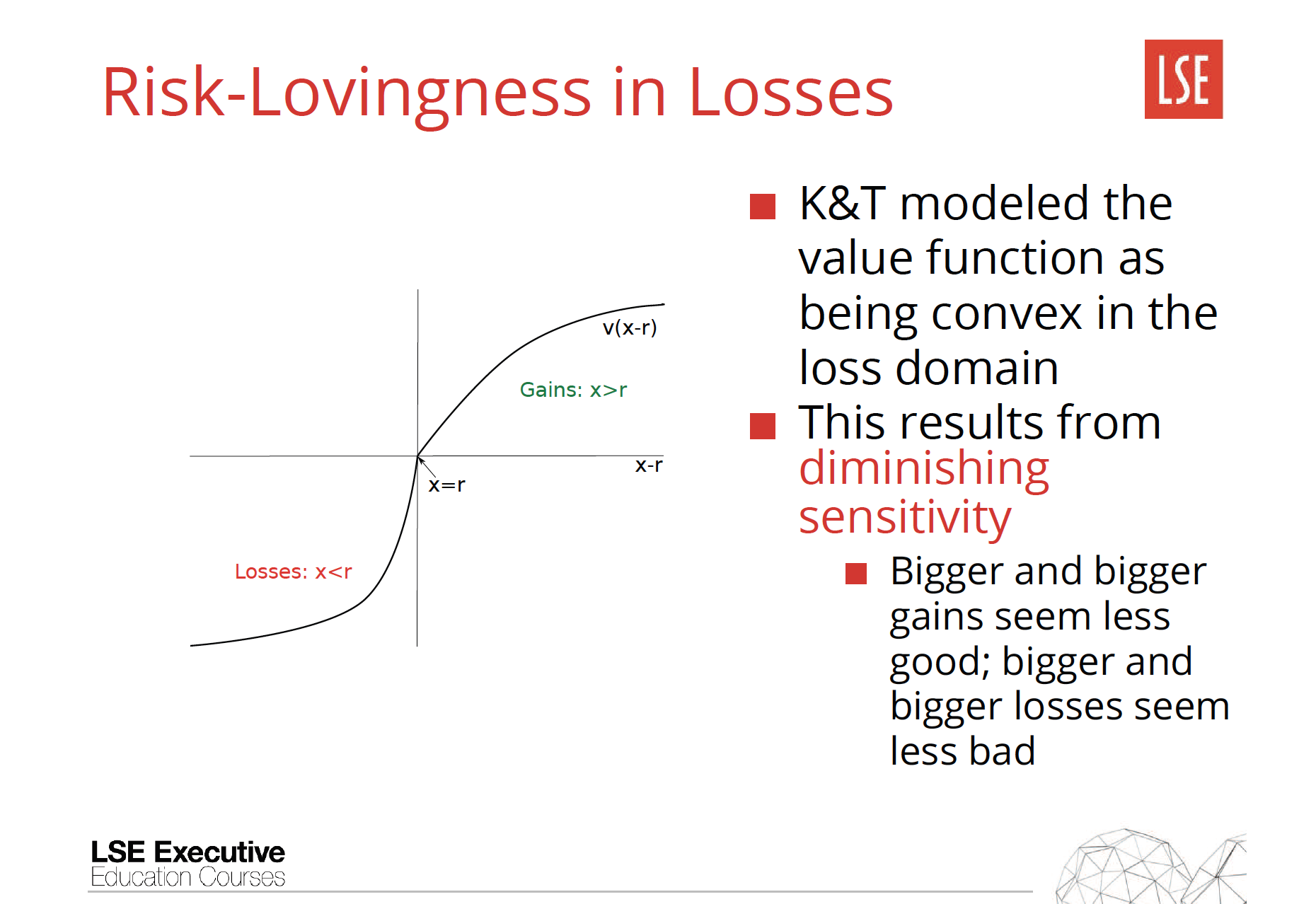

- Decision-makers are generally ‘risk-seeking’ when in the loss domain and ‘risk-averse’ when in the gains domain.

I found the most important graph in the course to be the slide below. The point ‘X’ indicates a unique ‘reference point’ for a decision and the graph illustrates that we are generally risk-seeking when in the loss domain and risk-averse when in the gains domain. Put another way, we would happily double up on risks in order to get a gain but once we have a gain we are more cautious and will often not take the risk again. This principle is evident in why gamblers continue to gamble.

Day 1, p. 27

- Decision-makers are highly sensitive to their reference point.

Reference points and who sets them are important determinants for our behaviour. The example of a fly placed in messy urinals for people to aim at illustrates how reference points can help people to change their behaviour – the reference point just needs to be transparent and, ideally, fun.

Day 5, p. 12

- Decision-makers are highly sensitive to the ‘default effect’

The importance of the default effect is ‘one of the most important recent discoveries in applied economics… In many different domains, people tend to stick with the option automatically assigned to them’. - Decision-makers are highly sensitive to size (e.g. whether the loss is big or small)

Diminishing outcomes exist for both risk-averse and risk-seeking behaviour. People tend to ‘over-weigh small risks’ and ‘under-weigh large ones’; we have a tendency to focus on small outcomes and not put as much due diligence into big outcomes. This is illustrated by consumers over-insuring for modest risks and under-insuring for big risks. In practical terms, this means that when their earnings are below a reference point, workers work hard to avoid a loss, but once the reference point is reached, there is less incentive to continue. This is called the ‘loss aversion effect’ and can lead to inefficient choices. Some groups tended to be more loss-averse than others: women more than men, older people more than younger people, wealthier people more than poorer people and those in blue collar occupations more than those in white collar occupations. An excellent practical example of this was provided by one of the participants. Uber drivers only have access to the last few hours of fees earned, rather than a full day. In the past cab drivers would work the day until they earned their reference point (say $200). This meant that often at the busiest time of the day (about 5.00pm) there were no taxis around. By Uber changing the reference point, more cars were made available at busiest times. - Decision-makers are sensitive to time preferences and revealed preferences

Laibson, McClure et al (2004) found that ‘choices involving immediate awards were processed using System 1, and choices involving future awards were processed using System 2’. Systems 1 and 2 are explained above. See also the discussion on present or future bias below. In addition, our actions and decisions do not ‘always reveal our true desires and preferences’. ‘Therefore we often create commitment devices to support our actions towards achieving our desires and preferences. One such example is our use of ’mental accounting’ where people create unique bank accounts for distinct purposes (e.g. a unique bank account for saving for a holiday). To understand the range of revealed preferences that people are using commitment devices to fulfill, check out www.stickk.com. - Decision-makers are sensitive to ‘framing effects’.

This was illustrated in a class exercise that was too long to be repeated here. In summary, the exercise illustrated that how we frame an option influences the decisions we make. This is not new in terms of marketing, but it became very obvious that our decision-making processes are being manipulated all the time. - Decision-makers are sensitive to ‘narrow bracketing’.

Kahneman and Tversky found that it was difficult for people to assess a prospect in isolation, but it was easy to assess whether this choice was better or worse than other options. This has important implications for public policy in that providing options or scenarios can affect decision-making. An example of narrow bracketing is when professional golfers focus on winning each hole rather than the total number of strokes in a game. When mixed with framing effects (see explanation above), it can be a very productive outcome for sellers. For example, insurance payments being framed in isolation as a value-add to consumers is framing insurance as small, in isolation and in the gain domain, therefore appealing to those who are risk-averse. - Decision makers are sensitive to the ‘isolation effect’.

Kahneman and Tversky in their 1979 paper state:

In order to simplify the choice between alternatives, people often disregard components that the alternatives share, and focus on the components that distinguish them (Tversky [44]). This approach to choice problems may produce inconsistent preferences, because a pair of prospects can be decomposed into common and distinctive components in more than one way, and different decompositions sometimes lead to different preferences. We refer to this phenomenon as the isolation effect.

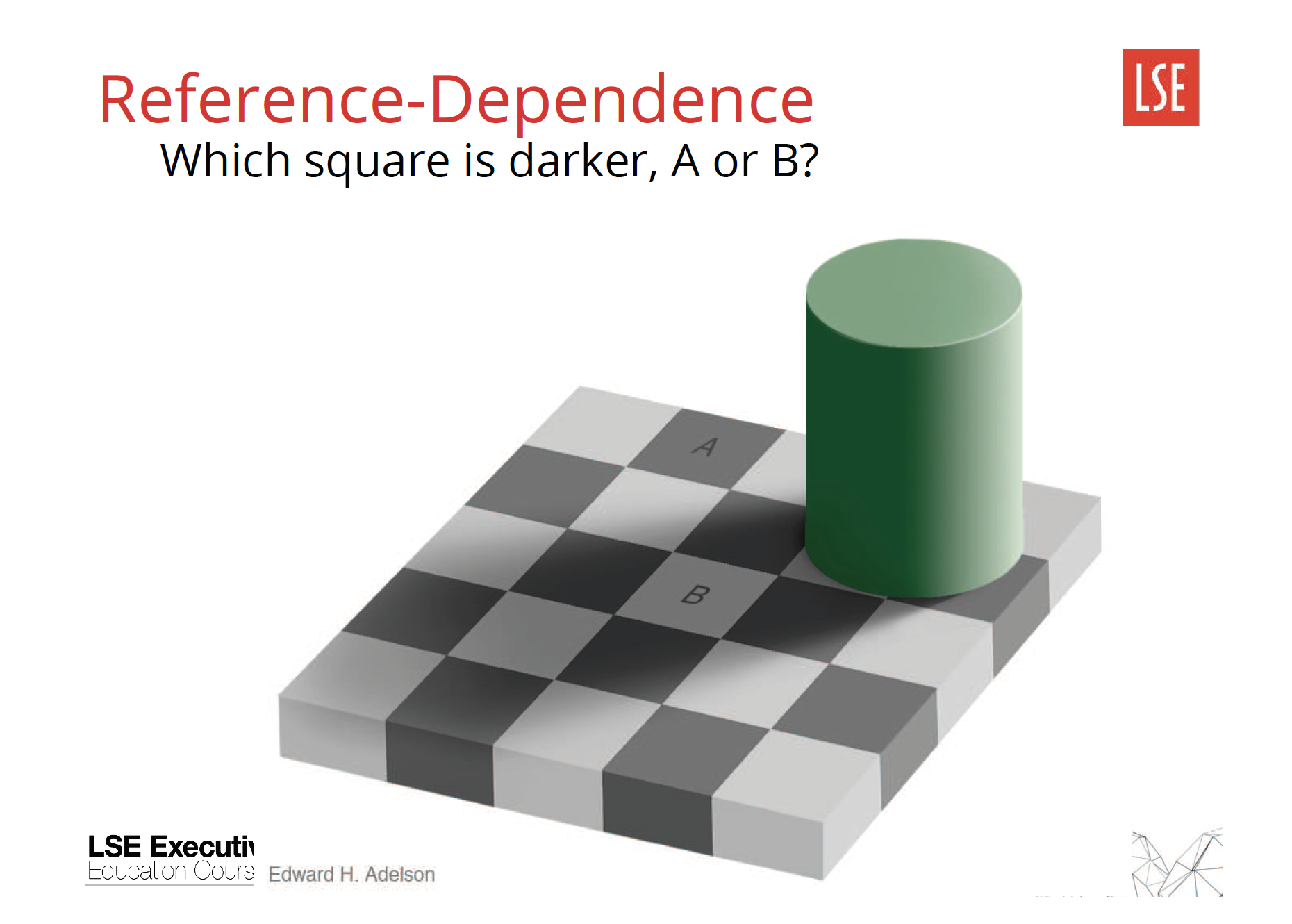

They found that although we might have the evidence in front of us, we do not necessarily correct our assumptions based on what we see – we have to work hard at this. This famous example asks the viewer which square is darker, A or B? In reality they are the same colour.

Day 1, p. 17

- Some decision-makers are sensitive to the ‘ambiguity effect’.

A number of people have an aversion to uncertainty. For example, someone with ambiguity aversion will under-value insurance, ‘because it will always be worthless if they buy it’. Hence ambiguity aversion ‘limits both risk taking and insurance demand’. - Some decision-makers are sensitive to the ‘endowment effect’.

The endowment effect refers to the phenomena of valuing something more because you own it, rather than if you are considering purchasing it. This effect arises because the reference point changes after we own an item. This effect does not apply to professional traders, but it does explain a little why we find it hard to sell things we own even if we are offered a good price.

More about the decision-making process

- Decision-makers tend to adopt either a ‘present’ or ‘future bias’.

If bias is solely anchored in the present, decisions are likely to lead to over consumption. This distinction is particularly relevant to long-term challenges such as climate change. If a decision-maker has a 100% present bias they will not make trade-offs about today for future gains. - Decisions-makers tend to adopt either a ‘naïve’ or ‘sophisticated’ approach.

Decision-makers can be sophisticated when making decisions in one area of their life and naïve in another. Sophisticated decision-makers are people who acknowledge that they want to make decisions that trade-off short-term losses in order to achieve long-term gains and will therefore ‘seek-out commitment devices’. In contrast, a naïve decision-maker tends to procrastinate and ‘believes their future preferences will be consistent with their current preferences’ (i.e. they do not need to seek out ways to support or reward their decisions as they are not hard decisions to make). Naïve decision-makers tend to get the big picture right by setting the right goal (‘I need to give up smoking’ and/or ‘I need to save for my old age’) but get the small picture wrong by failing to embed the right behaviour (by actioning that decision in terms of ‘I will stop smoking and start saving tomorrow’). As the lecturer noted: ‘a repeated small mistake is a big mistake’. Behavioural economics is really only interested in the naïve decision-maker as the sophisticated decision-maker tends to achieve their goals. Behavioural economics is about supporting the naïve decision-maker by either (i) turning them into a sophisticated decision-maker or (ii) changing the framework so that it is easier for the decision-maker to choose the right choice or harder to choose the wrong choice (i.e. creating inbuilt commitment devices such as supermarkets enabling consumers to open a Christmas shopping account early in the year or creating a further loss such as direct taxes on cigarettes). In class, this was followed by a deeper discussion about the difference between what a consumer wants to do/buy, what they expect to do/buy and what they will actually do/buy using the examples of gym membership and life-cycle saving and borrowing to illustrate short and long-term patience. The lecturer then asked which was better: to be sophisticated or naïve? Interestingly, he said there were some real benefits to being naïve: sophisticated decision makers tend to be pessimistic while naïve decision makers tend to be optimistic. Hence people that tend to follow naïve decision-making processes may dream more and dread less, which might be better in the long run. Some research by Aruely and Wertenbroch (2002) showed that a ‘partially naïve present bias’ might produce the best way to achieve goals: optimism with commitment devices. - Naïve decision-makers are highly sensitive to ‘heuristics’.

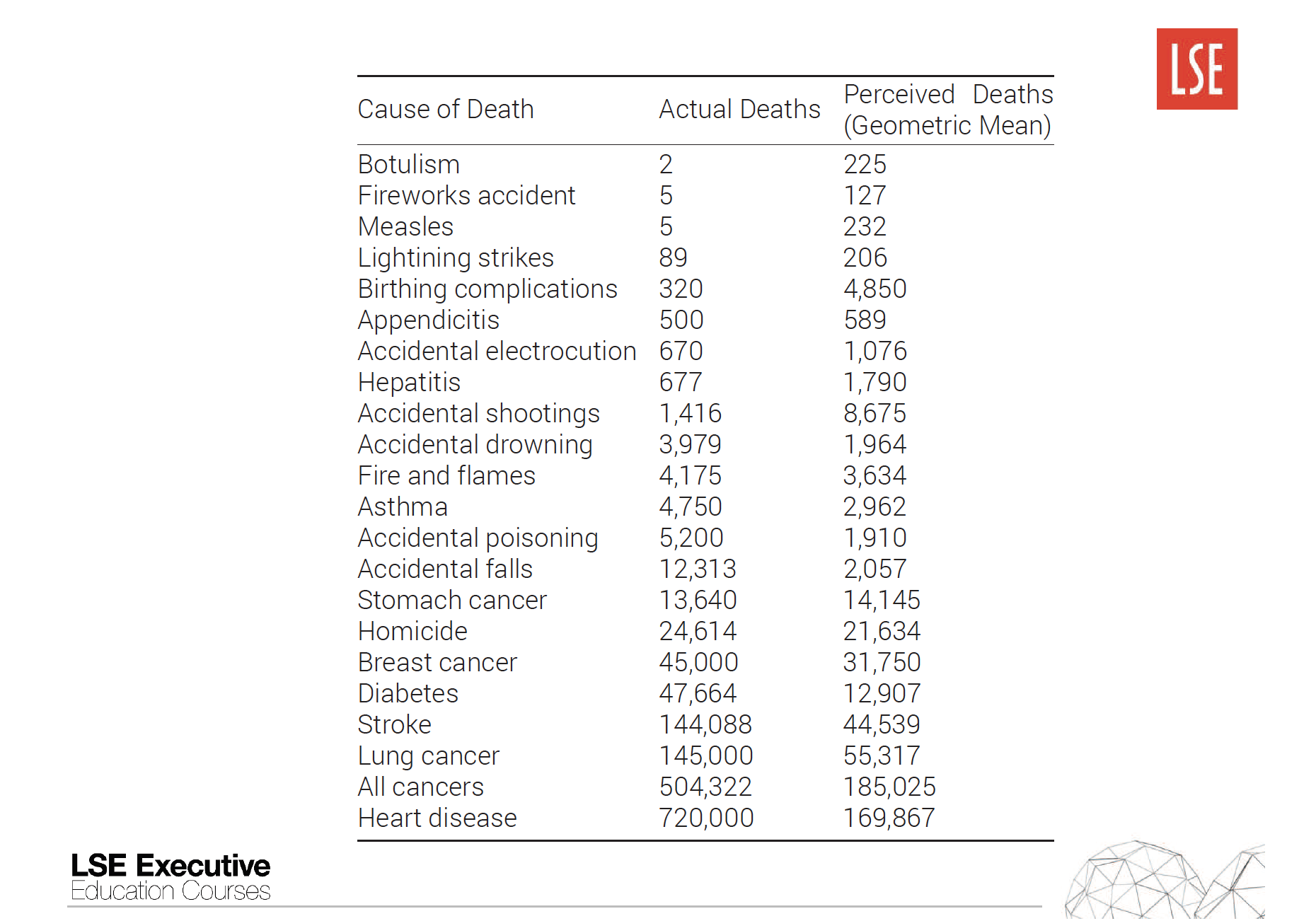

The mental shortcuts that naïve decision-makers use are called heuristics. We discussed three basic heuristics: availability of knowledge (i.e. recalling similar occurrences – see table below), anchoring (i.e. the weighted bias towards the first guess/data found as applicable to fake news and celebrity endorsements) and representativeness (i.e. ‘the tendency for people to use similarity as a proxy for probability’). I found this table on anchoring fascinating, as it indicates how uninformed we are about our lifestyle choices.

Day 4, p. 11

‘Representative heuristic’ can be explored in terms of the Gamblers Fallacy “the false belief that in a sequence of independent draws, an outcome that hasn’t occurred for a while is more likely to come upon the next draw” and the Hot Hand Fallacy “the false or exaggerated belief that a person’s performance varies systematically over the short run’ (it originated from basketball, hence the name).

- Some decision-makers are sensitive to ‘prosocial motivations’.

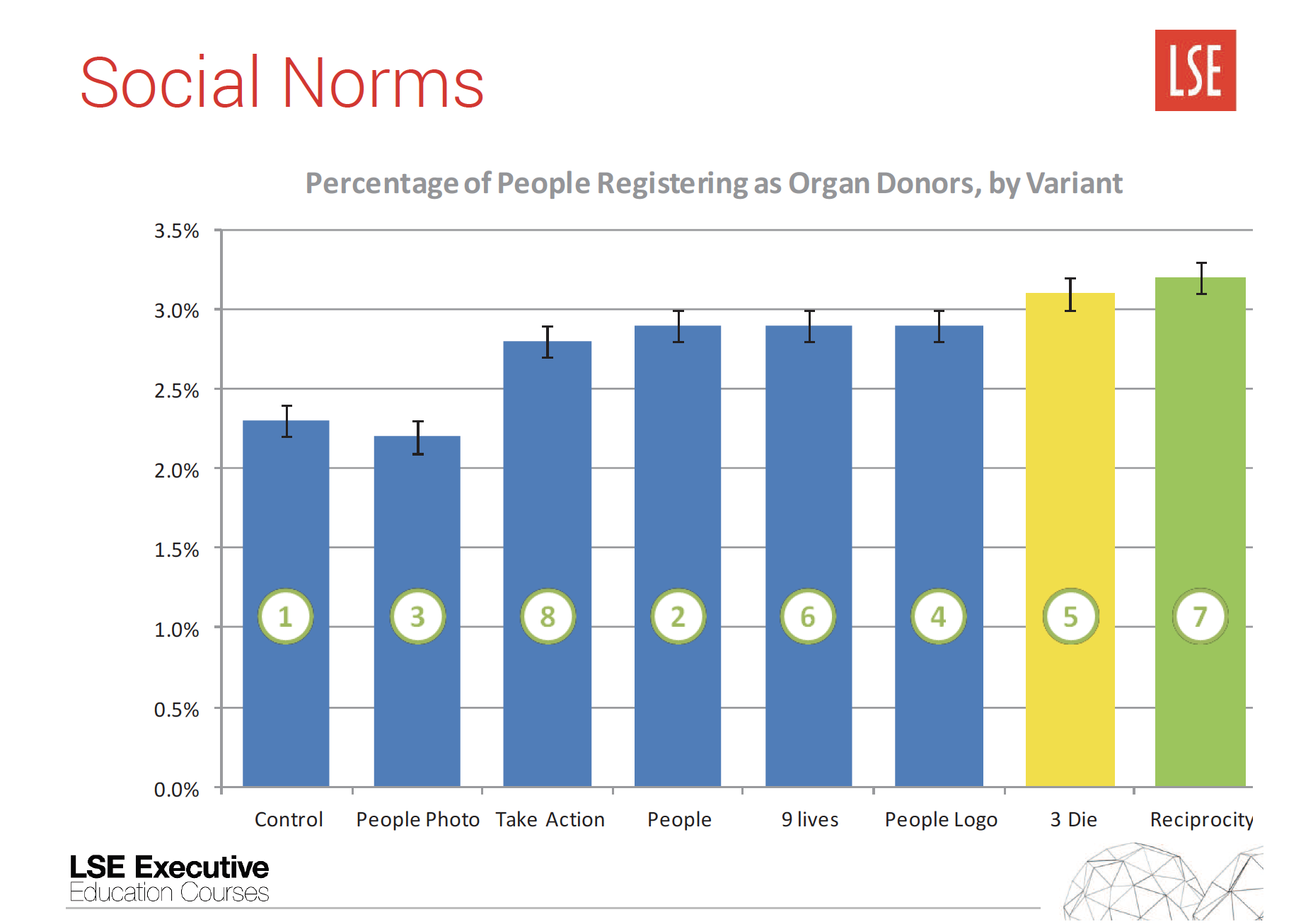

This was discussed in terms of how group dynamics play out when one decision-maker makes a gift to another given certain rules. This is particularly relevant in terms of poverty and inequity. Positive effects were strongest when personal exchanges (rather than the market) were utilised. The discussion reminded me of the Givealittle crowdfunding website. I was also particularly interested in the research on organ donors where they tried to achieve the same goal but applied different wording. Examples of phrases tested on the NHS website included:

Control: Please join the NHS Organ Donor Register.

Social pressure: Three people die every day because there are not enough organ donors.

Altruism (gain or loss): You could save or transform up to 9 lives as an organ donor.

Reciprocity: If you needed an organ transplant, would you have one? If so, please help others.

Policy expression: If you support organ donation, please turn your support into action.

The most effective of all the statements was the reciprocity phrase followed by the social pressure phrase, but the change was not as materially different as you would think.

Day 4, p. 56

- Organisations (and countries) might be able to build altruistic capital.

Ashraf and Bandiera (2017) suggest that in the future we might be able to diagnose, design and deliver policies to build altruistic capital. However, they believe ‘in general, more research is needed into whether and how altruistic capital can aggregate and provide value within an organisation, and how it can be leveraged or depleted by organisational policies and norms’.

Encouraging the adoption of behaviours that align with intentions

- Applying a ‘nudge‘ or removing ‘sludge‘.

Nudge and sludge were both discussed as a way of describing ways to improve the system to develop better outcomes. The idea of nudge was popularised by Richrd Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (2008). Nudge refers to how small actions, nudges, can bring about improved behaviours (e.g. the fly on the urinal), usually without any change in costs or the choices offered. Sludge refers to actions and processes that exist with a system to make compliance difficult or to prevent optimal decisions or use of time and resources. The concept is that you can improve the system by adding nudges and removing sludge. - ‘Choice architects‘ must be transparent, especially those operating in the public service.

‘Anyone who designs the environment in which people make choices is a choice architect’. Examples include improving menus, user experiences, form designs and store layouts. Importantly, environments are already pre-loaded with some form of choice architecture, so it is useful to understand what currently exists before adjusting the system.Public policy requires clarity and high levels of transparency over who is framing what for whom, particularly what the goal of the nudge is, which ‘self’ is the primary focus and who wins and loses over what time frames if the nudge works. Sugar tax in the UK was discussed as an example. Emphasis was placed on the importantance of determining the goal of the nudge first and then using the goal to develop the nudge. Discussions emphasised that it was important to not provide too many choices or too few choices and that ‘in complex situations, there is a good chance that a well-chosen default option will be a better choice than the one most people will choose’. They also recognised the tension between the libertarian approach (i.e. people are free to choose) and the paternalistic approach (i.e. people need help from government to make better choices so that they live longer, healthier and better lives). Ethical concerns about manipulating people’s choices and the fact that our choices are being manipulated all the time (e.g. by the chocolate and lollies at the supermarket counter) were also discussed.Governments have continuously used behavioural economics to change behaviour (e.g. graphic health warnings on cigarette packets) but technology, particularly algorithms, enables this practice to be further embedded and streamlined in public policy. I liked how one of the professors suggested that behavioural economics was not about removing the range of choices but enabling people by making their preferred choice easier to select. He said that behavioural economics is hard work and you always need to check in that what you are doing meets the headline test (in the local newspaper).

Behavioural finance

- The ‘efficient markets hypothesis‘ is questionable.

The lecturer argued that stock prices are far too variable to follow the efficient markets hypothesis. The assumption that market prices reflect all available information can take one of three forms:- Weak form: ‘past prices or stale information should not predict price changes’.

- Semi-strong form: ‘publicly available information should not affect current prices because it gets incorporated instantaneously’.

- Strong form: ‘inside information should not produce abnormal returns for traders’.

- Those that trade least, make the most.

The lecturer explained that, in general, small traders are less sophisticated and, as such, trade too much and make too many errors whereas big institutional investors trade less often and play the longer game. One of the reasons for this is that each trade costs money. - AI will have an impact on the market.

This is for a number of reasons. AI will enable all information to be digested equally whereas at the moment ‘hot news’ biases traders to focus on highlighted information while ignoring other information hidden further down. Secondly, the time taken to read information will be minimised, possibly making the efficient markets hypothesis more plausible. - Some investors are sensitive to ‘home bias‘.

For example, ‘investors in the United States, Japan and the United Kingdom allocate 94%, 98% and 82% of their equity, respectively, to domestic equities’. - Some investors are sensitive to ‘diversification bias‘.

The lecturer argued that you need to look deeply at each portfolio to ensure diversification actually exists, rather than simply looking as though it exists. ‘The way financial planners present choices affects [portfolio investor choices].’ - ‘Cohort effects‘ exist.

‘Depression babies [are] more pessimistic about stocks than boomers’ and ‘people coming of age in recession of 70s and early 80s [are] more pessimistic’. - ‘Herd effects‘ exist.

‘Traders who overestimate other’s rationality will interpret the momentum … as reflecting new sources of good news.’