As part of the Institute’s ongoing work on how to build an informed New Zealand through Project ReportingNZ, I sat down with a number of organisations from the financial reporting sphere during my recent trip to London. The purpose of the meetings was for me to gather expert perspectives on the nature of corporate disclosures in the United Kingdom, particularly in relation to climate change. Currently, large organisations in the UK are subject to more stringent climate-related public disclosure requirements than New Zealand companies (e.g. disclosure of GHG emissions), despite no specific requirement to report directly on climate change. Given this, and the fact that the Zero Carbon Bill is largely based on the UK’s climate change legislation, it seemed fitting to use the UK as a model for some insights into how New Zealand’s reporting framework could be strengthened to address climate change.

The consultation meetings also gave the Institute an opportunity to get feedback on the final draft of Discussion Paper 2019/01 – The Climate Reporting Emergency: A New Zealand case study. Insights from the discussions I had were subsequently incorporated into the discussion paper.

On behalf of the Institute, many thanks to all the organisations that gave up their time to talk to me. I would especially like to thank the following people: Jimmy Greer (ACCA); Nathaniel Smith (BEIS Green Finance Team); Mardi McBrien (CDSB); Dan Wiseman (ClientEarth); James Ramsay, Anita Baranyi and Gavin Tivey (EcoAct); Hannah Armitage, Thomas Toomse-Smith, Andrea Tweedie (FRC Lab); Matt Chapman and Marie Claire Tabone (IASB); Juliet Markham and Jonathan Labrey (IIRC).

The insights that were shared with me have been instrumental in shaping the next steps of the Institute’s work programme, particularly in the area of climate reporting. Please note that the opinions in this blog post are not necessarily the official positions of the organisations listed above.

Key takeaways

- The distinction between financial and non-financial information is no longer useful

- Climate issues are impacting on financial statements now

- What is useful is whether information is ‘material’ (or not)

- The annual report must be reclaimed as the core provider of external recurring, reliable material information about an entity

- The debate will be around what is material (or not). Whether something is considered material will depend on who the audience is, the probability of an event occurring and whether the information is past or forward looking (and over what time frame)

- Where and how ‘material’ information is reported in the annual report requires further consideration. For example, we would argue all climate-related disclosures should be required to be reported in each entity’s annual report (e.g. A Statement of Climate Information)

- The difference between preparation, assurance, publication will continue to drive the dialogue. For example, an annual report could be prepared but not assured and not made available to the public. In contrast, an annual report could be published, assured in part and the full annual report could be made available on a public register. Balancing the tensions between what information is required for the public interest versus what should be kept confidential to meet private interests will continue to be challenging

- There is a difference between compliance and best practice (rules versus principles)

- There are short-term risks of climate change. One of the short-term risks we face is how humans will behave to a planet that is overheating. What does panic on a world scale look like?

- Reporting and assurance of GHG emissions will be key

- There is a need to ensure board information (i.e. strategic outward looking information) is kept seperate in the annual report from management information that is operational and often backward looking

- The quality of the narrative needs to be improved so that readers of the annual report gain an integrated understanding of what the entity considers important, how it manages progress and what it aims to achieve with its current and future business model.

Comprehensive answers

As a result of our research, we had prepared a set of questions to shape the dialogue. Some were specific to particular organisations, but the 13 questions below were the common questions I used to structure all my discussions. In many cases the questions sparked ongoing conversations that continue via email. Below I present the insights I gained from responses to each of the questions. Please note specific opinions are deliberately not attributable to particular people/organisations.

1. Has the strategic report requirement introduced by the UK Companies Act been successful in improving the quality of disclosures?

The UK Companies Act 2006 introduced the requirement for companies to produce a strategic report as part of their annual report for each financial year. The general consensus was that this requirement had been successful in increasing entities’ overall rate of disclosure, including disclosure of climate information. However, the strategic report requirement did not specifically make climate-related disclosures mandatory and there was some concern that the information disclosed by UK companies was still not of a high enough quality for investor needs.

The 2018 Guidance on the Strategic Report produced by the UK Financial Reporting Council (FRC) outlines one of key components of a strategic report as describing ‘principal risks the entity faces and how they might affect its future prospects’ (p. 12). Several organisations explained that this was the main hook under which companies have been disclosing climate-related information, although the new requirements to report on GHG emissions under the Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting legislation provide an additional framework for such information. The guidance also mentions providing ‘relevant non-financial information’, which could include climate-related information such as carbon and greenhouse gas emissions (p. 12).

Although entities were judged to be making effective disclosures around how their business will affect the climate in terms of CO2 emissions and other metrics, they were said to be struggling when it came to disclosing how climate change would affect their business model. This was identified as the much broader risk for companies and would only become more important as the climate’s effect on the economy becomes more pronounced.

It was noted that most companies were disclosing information (both climate-related and otherwise) at the level of legal compliance rather than of best practice. Several interviewees said that there is currently no mechanism by which companies could be incentivised to disclose to the best practice level. However, the strategic report requirement does provide a framework that allows comparison of disclosures across different companies.

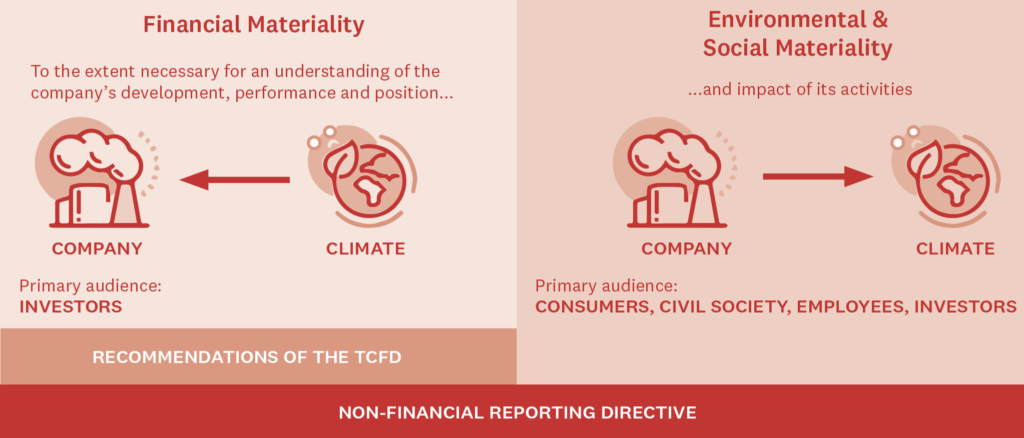

Double materiality perspective diagram – Figure 28 of Discussion Paper 2019/01 (adapted from EU, 2019, p. 7)

2. Has or will the IASB’s review of the Management Commentary Practice Statement have an impact on the strategic report? Is IASB’s proposed revision likely to change this?

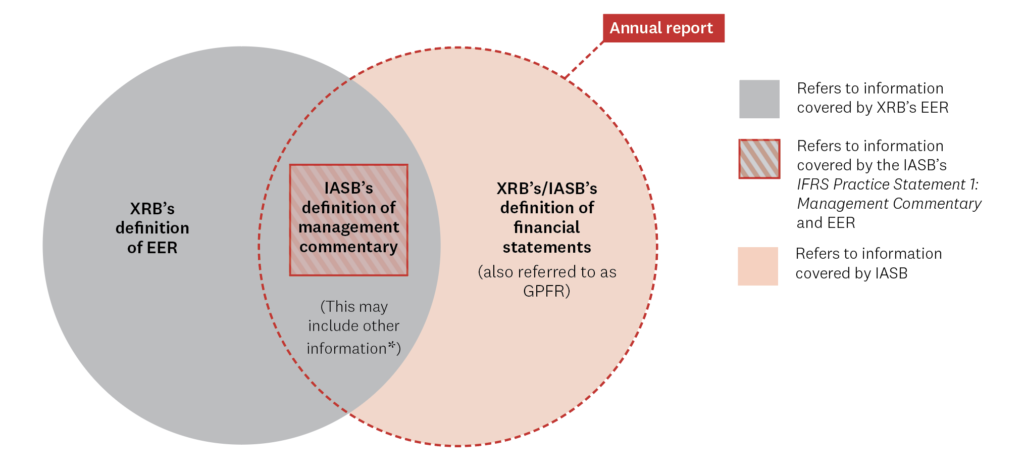

I was informed that IFRS Practice Statement 1: Management Commentary relates to broader financial information rather than non-financial information. This includes information that could affect an entity’s cash flow in the long term, and may therefore include climate-related risks. The practice note was suggested as a useful tool for conveying ESG information relevant to climate change.

Distinctions between XRB definition of EER and IASB definition of management commentary – Figure 27 of Discussion Paper 2019/01 (adapted from Figure 9, section 2.3.3)

3. What is the current thinking of the TCFD and what does that mean for SMEs?

Those I spoke to said that the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework has been broadly endorsed by both companies and investors as a practical methodology for disclosing consistent climate-related financial risk. Similarly to replies about the UK Companies Act (see question 1), there was some concern that TCFD recommendations could become the ceiling for climate-related reporting if they become mandatory in 2022 as expected. Instead of this, interviewees thought that the TCFD recommendations provided a platform to be built on.

This question was of specific interest to me because New Zealand’s business sector is 75% small and medium enterprises (SMEs), so I was curious to see whether those I spoke to thought the framework could be applied to companies of this size. Most replies noted that the TCFD framework was originally intended for large companies with over 500 employees, which traditionally have the most impact on the climate. However, because the framework is principle-based rather than prescriptive, there was still some potential for application to smaller entities, particularly in terms of the scenario analysis. However, there was some concern that the quantity of information required to be captured for disclosures made in line with TCFD recommendations could be an administrative burden for smaller companies.

4. What are the chances that the IASB will produce climate change guidance/standards over the next five to ten years?

The overwhelming response I received was that the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) is highly unlikely to produce any guidance or standards for climate change in the next five to ten years. It is instead likely that the IASB provide some guidance around climate change in the upcoming management commentary guidance, but only in terms of the impact it will have on financial accounts. This guidance will focus on the material impacts related to financial statements, so it will not include non-financial information.

Climate could still be relevant in how it relates to impairments, fair value estimates, decommissioning liabilities and other elements. This could provide some guidance around climate-related disclosures but it would be only as it materially relates to companies’ financial accounts.

5. What is the appetite to extend the audience of financial statements from solely primary users to stakeholders?

A number of the organisations I spoke to confirmed that there has been a shift away from thinking of investors as the only users of financial statements in the UK. It was positive to hear this development given the general aim of the Institute’s Project ReportingNZ. There is currently an open discussion in the UK accounting field about the role of wider stakeholders and users of the annual report. The UK’s Financial Reporting Council (FRC) project on the future of corporate reporting was particularly mentioned. There was some discussion about who is considered a stakeholder and how to communicate to them effectively. I was informed that this discussion is also reflected in how the accounting standards are written, as NGOs and bodies that represent civil society are now consulted in the development process, where they would not have been ten years ago.

However, I did hear some concern about a growing lack of focus in the reporting space. The pushback was from some organisations that thought broadening the audience for financial statements could cause confusion over their purpose and suggested that non-financial information could be disclosed elsewhere, such as in the management commentary.

6. Is there any work or thinking regarding assurance of the chair’s report, or specific information in the management commentary?

I was informed that it is currently difficult for auditors to assure climate-related information as the standards are still evolving. Furthermore, there appears to be a skill gap for assurance of non-financial information. Chairs in the UK are still cautious when signing off on non-financial information in annual reports, especially emerging climate information. By way of addressing this issue, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) has an ongoing project on the assurance of emerging forms of reporting.

The caution of UK chairs and directors was generally believed to be a result of high scrutiny facing the auditing profession in the UK due to several high-profile corporate governance scandals. There was mixed opinions as to whether this was a positive development in the assurance field. Was it better for a chair’s report to include information of a low quality or no non-financial information at all? In relation to this, the Brydon Review into ‘The quality and effectiveness of audit’ was mentioned as key future development for the UK auditing profession.

7. What is the general response of the auditing profession to the FRC investigation into Carillion’s collapse and the possible High Court lawsuit (e.g. there is a threatened legal action by US law firm Quinn Emanuel against the Big Four firms over audit work, see Financial Times on 5 August 2019 – author Tabby Kinder.)

Carillion was a large British construction and civil engineering company that went into liquidation in 2018. As a result, FRC began an investigation into the misrepresentation of financial statements by the company. FRC subsequently also launched investigation into the failure of auditors to accurately verify Carillion’s financial information.

The Independent Review of the Financial Reporting Council undertaken by the government (informally known as the Kingman review) was also mentioned a number of times. The report looked into flaws in the FRC oversight of Carillion and how it related to the collapse. The report also included some analysis of corporate reporting in general and a discussion of who the intended audience of annual reports should be going forward as part of its remit to ‘make recommendations on how to reform the Financial Reporting Council to ensure the UK has a world class audit and accounting regulator’. This report seemed to cause somewhat of a shakeup for the future of auditing profession in the UK. Environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) was expected to come more to the forefront of UK corporate reporting as result.

There was a general concern that auditors aren’t properly accountable for their work. I was told that, in the UK, auditors are quite insulated from direct lawsuits from investors. Instead, there is an emerging dialogue between concerned investors and auditors about what their work should have to entail. A number of the organisations I spoke to surmised that, as a result of the fallout of the collapse, audit firms in the UK generally have been much more cautious in the companies they select as clients.

8. How is legal liability around the failure to disclose climate risks evolving?

Legal action being taken against companies that fail to address climate related risk is a recent development in the UK but it was believed to be developing quickly.

A notable example mentioned to me involved the environmental law charity ClientEarth. In 2018, the charity publicly reported a number of companies to the FRC and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) for failing to properly address the risks and opportunities of climate change and the transition to a low emissions economy. While the companies did mention emissions in their financial statements, in ClientEarth’s view, they did not disclose relevant material climate-related trends and risks to investors and therefore were in breach of the strategic report requirements in the UK Companies Act. ClientEarth also sent letters to the companies’ auditors to hold them to account for signing off on this information. Both actions were intended to push financial regulators to hold companies accountable.

The consensus across interviewees was that companies were slowly but surely beginning to address climate risks, particularly transition risk. Although, companies were not necessarily currently being held to account by regulators to address this risk, future legal action was seen as likely to have an impact on this. The fact that very few companies that committed to the TCFD recommendations have yet to implement the recommendations in their reporting was cited as an example of something that could result in legal action in the future.

9. What is the general response to the London Stock Exchange (LSE) considering delisting companies that fail to make climate-related disclosures? This idea was recently supported by the UK Labour Party.

Many of the organisations I spoke to were interested in the idea of the government taking punitive measures against companies failing to make climate-related disclosures, although most did not necessarily support delisting companies from LSE as the specific method. It was seen as too much of an extreme measure for the LSE to drop major companies and they should instead be allowed a transition period. The London Stock Exchange Group has produced its own ESG guidance, but this is of a lower requirement than what was being suggested by the UK Labour Party. (The Labour Party has since also taken a more moderate position, suggesting mechanisms other than delisting).

Several responses were about investor initiatives with similar goals of pushing companies to make proper climate-related disclosures. From the investor perspective, the best mechanism to achieve this is to pass shareholder resolutions at Annual General Meetings (AGMs) requiring companies to improve their climate-related disclosures. It was mentioned that earlier in the year a group of BP investors called for the company to align its business strategy with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Signatories to the Climate Action 100+ investor initiative were the major coalition pushing for this resolution.

None of the interviewed organisations expressed a preference for the most effective way of getting companies to disclose climate information, whether mandated by government or through investor initiatives. One suggestion was that companies should be required to align their business strategy with the Paris Agreement, but it was unclear what specific mechanism could or should be used to do so.

10. Is there any work being undertaken to assess social enterprises in terms of whether their operations are being properly captured by existing reporting frameworks?

Currently the UK Green Finance Strategy is focused on larger for-profit enterprises and requires them to disclose relevant climate information. The view was that these types of entities have the largest impact on the climate and are therefore the most important entities to report on climate information. It was suggested that further down the line there could be discussion around how to capture other types of entities, such as social enterprises, in reporting frameworks.

11. How can we address the problem of multiple reporting guidance? Is the July 2019 report by the Corporate Reporting Dialogue part of a possible cooperative solution?

There was a mix of responses to this question, with some interviewees taking the view that it may be unhelpful to have guidance with the same objectives expressed in different formats. Conversely, there was support for guidance that would address a number of different standards. There was a common opinion that the Corporate Reporting Dialogue (CRD) should look to combine and synthesise these views in its future work and many concurred that the multiplicity of reporting guidance was an issue that drained companies’ reporting capacity.

The CRD’s Better Alignment Project is a collaboration between several reporting standard-setters and framework providers which intends to ‘better align the frameworks in the sustainability reporting space (SASB, GRI, CDP) and frameworks that promote further integration between non-financial and financial reporting (IIRC, CDSB)’. The project will also enable organisations to compare their frameworks against TCFD recommendations and identify metrics that could be aligned.

It was thought that the possibility of the TCFD recommendations becoming mandatory by 2022 would contribute to alignment between different frameworks, not just in the sustainability space; as the TCFD framework is principles-based, it can be flexible enough for other frameworks to feed into it. One development mentioned in this area was the CDP Climate Change 2019 Questionnaire, in which each question links to the TCFD framework.

12. Any thoughts on the July 2019 UK Green Finance Strategy? Do you know how the government is hoping to meet the goal: ‘The Government expects all listed companies and large asset owners to be disclosing in line with the TCFD recommendations by 2022’ (p. 23)?

The answers to this question were in two parts. I asked each of the interviewees about what they thought the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) considers ‘large asset owners’ in the UK Green Finance Strategy. The current understanding was that the term refers to pension and superannuation funds and institutional investors, although no specific definition is provided in legislation to allow for a broader interpretation of ‘large asset owner’ if necessary.

A number of the organisations I spoke to believed that the TCFD framework was already de facto mandatory. The argument was that because TCFD recommendations were the industry standard for investors, listed companies were already expected to be disclosing at this level, especially given that existing disclosure requirements in the UK Company Act are principle-based. This view is supported by the fact that a significant amount of UK companies are already working towards disclosing in line with TCFD recommendations, however this is occurring slowly.

Differences of definition over what constitutes ‘green finance’ were seen as a fundamental obstacle that would need to be overcome in the implementation of TCFD recommendations, as was a professional skill gap similar to that of assurance of non-financial disclosures. The key issue was that pricing of climate risk needed to be considered as part of mainstream finance; however, what this specifically entails was not necessarily clear from my conversations.

It was terrific to note the joint response to the Green Finance Strategy by financial regulators the FRC, Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and The Pensions Regulator (TPR).

The FRC Lab has just released a report Climate-related corporate reporting (October 2019) that discusses the TCFD and provides some further examples of good practice. It was being prepared while I was in London and I found this excerpt about the role of investors particularly interesting:

‘While the focus of this project is on reporting by companies, it is clear that investors are seen as part of the solution to managing climate change. Investors themselves are also under pressure to report on climate issues under new regulations and client requests, where mandates from asset owners are increasingly referring to environmental, social and governance issues.

Indeed the TCFD framework and the UK Government’s expectation [that listed companies and large asset owners should disclose in line with the TCFD recommendations by 2022] relate as much to investor reporting as they do to company reporting. Information needs to flow through the ecosystem in order to meet the need not only for decision-useful information, but also to meet the needs of investors in carrying out their own reporting.’ (FRC Lab, 2019, p. 4)

13. What other emerging trends or outstanding issues are you seeing in regard to improving climate-related disclosures?

Many organisations that I spoke with thought that, after considerations about making the TCFD recommendations mandatory are resolved, the next step for climate-related disclosures would be to push businesses to publish Paris Agreement aligned business strategies. This was already strongly supported by investor initiatives such as Climate 100+.

Another observation was that businesses’ current planning cycles constitute a structural barrier to long-term planning and therefore to considering the longer-term horizons of climate risk. Businesses report on quarterly and yearly cycles and plan business strategies usually for a period of five years or fewer. Businesses will need to make trade-offs as they starting investing now or in the short term for the transition to a low emissions economy, which may only produce value for them over the much longer term. This is particularly difficult for chairs and chief executives to commit to when they may not see any gain during their tenure.

I also heard that businesses and regulators are struggling to apply the scenarios proposed in the TCFD framework. Many organisations find scenarios difficult to understand, because they are used to seeking certainty in their planning and want to be able to predict the next five years. This will be a difficult shift in thinking for a lot of organisations.

On behalf of the Institute, I want to thank all the organisations that gave up their time to talk to me. The insights that were shared have been instrumental in shaping the next steps of the Institute’s work programme, particularly in the area of climate reporting.

Background to Project ReportingNZ

The aim of Project ReportingNZ is to contribute to a discussion on how to build an informed New Zealand. This year, the Institute’s work in this project has been shaped by the alarming state of climate reporting within New Zealand. Most recently, this work has culminated in the publication of Discussion Paper 2019/01 – The Climate Reporting Emergency: A New Zealand case study. We could not have produced this publication without a significant amount of input from other parties; thank you to everyone who has been involved.

Next steps

- Report 17 – ReportingNZ: Building a Reporting Framework Fit for Purpose (in press)

This Project 2058 report aims to lay the groundwork for a comprehensive review of New Zealand’s reporting framework. Such a review would have the end goal of improving New Zealand’s information infrastructure, and making it fit for purpose for both users and preparers by making information (especially climate-related information) useful, accessible, accurate, timely, cost-effective and comparable. - Working Paper 2019/07 – A Review of the Accounting and Assurance of GHG Emissions (in press)

This working paper seeks to answer a series of questions about GHG emission reporting as disclosed under a range of international climate reporting regimes. Such questions may include the following: Which entities should report? Where should GHG emissions be disclosed? What methodologies should be used? What GHG Protocol scopes (1–3) should be reported? Should emission disclosures be assured? - Working Paper 2019/08 – A Review of Directors’ Report Requirements in New Zealand and Selected Overseas Countries (in press)

This working paper will provide a comparison of directors’ report requirements in New Zealand and internationally. It is expected to highlight the weaknesses in New Zealand’s reporting infrastructure that mean the country is not yet well-placed to follow the UK method of requiring climate-related disclosures. - FSB-TCFD Workshops: Practical steps for implementation

The Institute is partnering with law firm Simpson Grierson to deliver two workshops in Auckland and Wellington that will explore the implementation of the Recommendations of the TCFD in the context of New Zealand’s climate reporting framework. The purpose of the workshops is to raise awareness and assist in navigation of a (currently voluntary) climate reporting framework that has had significant international uptake and for which there is growing interest in New Zealand. Speakers include the Michael Zimonyi, Policy & External Affairs Director of the CDSB, as well as policy-makers, regulators, private sector leaders and early implementers of the TCFD recommendations. - Explore the idea of a New Zealand Green Finance Strategy

This would be along the lines of the UK Green Finance Strategy (see Section 7.5 of the discussion paper).

I am standing next to a room at the IASB named after the Waikato River in New Zealand – very cool!