In April 2023, two of us from the Institute were fortunate enough to travel to Bhutan, a small kingdom gently tucked far away in the Eastern Himalayas. Bhutan, called Drukyul by the Bhutanese, is known as the mystical land of the druk yul (thunder dragon), which can be seen on the country’s flag. The landlocked country has an estimated population of 770,400[1] and a total land area approximately seven times smaller than New Zealand.[2] Despite sitting quietly between two superpowers, China and India, Bhutan has always lived by its own rules. Through thoughtful leadership and bold public policy, the country has worked hard to protect its unique cultural heritage and natural environment.

Bhutan has been described by some as the most remote and untouched place on earth, only welcoming (heavily restricted) tourism in 1974,[3] television and internet in 1999[4] and democracy in 2008.[5] The country’s culture, legislation and policy are deeply rooted in Buddhism, to the extent that Bhutanese do not kill animals in their country, but import meat from neighbouring India instead. Over the course of our travels, we learned about the Buddhist value system and Bhutan’s vision for the future, and, most importantly, had the opportunity to understand the public policies that have shaped this distinctive country.

Over our time in Bhutan, we found local people generous with their time, curious about New Zealand and interested in sharing their distinctive culture and society with us. Our discussions were filled with questions from both sides as we worked to understand what we could learn from one another. As a result of our research and discussions, we came home with ten policy ideas that we think would be beneficial for New Zealanders to consider. We are looking forward to using Bhutan as a case study in our research to see how these ideas can be applied in a New Zealand context.

These are our top ten policy ideas New Zealand could learn from Bhutan:

- Ecological corridors

- Protecting natural areas constitutionally

- High-value, low-volume tourism, including a fee for visitors

- Observational data used to engage youth with biodiversity and climate change

- Gross National Happiness (GNH) index

- Parliamentary system with non-partisan leadership in local government

- Eligibility criteria for public servants

- National Identity Act, including a Digital Wallet

- Zero Waste Strategy

- Bhutan for Life – a new funding mechanism

Flag source: Norbu, D. and Karan, P. (28 April 2023). Bhutan. Retrieved 13 June 2023 from www.britannica.com/place/Bhutan

Map of Bhutan marked-up to show the locations of our trip in red, connected by a red line to show our route. Original map of Bhutan retrieved 2 August 2023 from www.smarttravelasia.com/BhutanMap.htm

By the numbers – Bhutan in comparison to New Zealand

| Indicator | Bhutan[6] | New Zealand[7] |

| Population | 777,486 | 5,112,600 |

| Life expectancy | 72 | 82 |

| Forest Area (% of land area) | 71.4% | 37.6% |

| Total GDP (billion US$) | 2.54 | 249.89 |

| CO2 emissions (tonnes per capita) | 1.4 | 6.8 |

| Primary exports | Electricity is the principal export, followed by copper wire and cable, calcium carbide, metal alloys, cement, and polyester yarn.[8] | Agricultural products (meat, dairy and fruit and vegetables) are principal exports, followed by crude oil, wood and paper products.[9] |

The context: why Bhutan?

We were initially drawn to Bhutan in order to understand the country’s world-leading approach to conservation, sustainable development and biodiversity policy. Low carbon emissions and sequestration of carbon in vast forests means Bhutan has received the title of the ‘world’s first carbon-negative country’ – an impressive accolade.[10] Bhutan’s public policy has been carefully designed to create balance between environmental protection, community values and economic development, which is part of the Buddhist concept of finding harmony through the ‘Middle Way’.

When the Institute first started to scope the idea of ecological corridors for New Zealand in 2018 (see the original think piece), we found Bhutan had already successfully implemented corridors to connect national parks along the length of the country. Bhutan’s corridors were established in 1999 and bestowed as a ‘Gift to the Earth’ from the Kingdom.[11] Ever since then, we (and the rest of the world) have been watching Bhutan to see how the idea has worked in practice, and have observed their progress with other exceptionally progressive policies, such as using a Gross National Happiness (GNH) index to measure citizen wellbeing and to determine future policy, and enshrining protected forest area in their Constitution (see these in more detail below).

A rhododendron tree over 100 years old. Rhododendrons are endemic to Bhutan.

Bhutan’s strategy for the long term

Bhutan’s public policy strategy for the long-term sits under the country’s uniquely young and innovative Constitution. In 2008, Bhutan became one of the world’s youngest constitutional monarchy’s while in comparison New Zealand is connected to one of the oldest, the United Kingdom. When crafting its constitution, Bhutan has managed to carefully incorporate strong cultural, community and environmental values and protect them over the long-term. By using the constitution as a guide to steer the country in the right direction, Bhutan has protected the rights of people and the environment in all future public policy. You can read a full copy of Bhutan’s constitution (with areas we have found particularly relevant highlighted in yellow) here.

Bhutan uses a planning process that encourages long-term strategic thinking, a concept that is often neglected in New Zealand due to our relatively short three-year election cycle. Bhutan’s Government works with two types of strategic planning: a Five-Year Plan (currently up to the 12th edition), and a Ten-Year Plan. The ten-year plan involves designing a long-term strategic vision, and the five-year plan outlines how this will be achieved, taking policy tools (such as the Gross National Happiness index) into account. This holistic approach to planning means Bhutan is always looking forward, working to see how public policy can work for the whole community.

Looking into the future, Bhutan has a number of other ambitious policy goals and projects designed to absorb carbon, protect biodiversity and safeguard the environment.[12] During our trip we saw that as well as designing innovative public policy, Bhutan is also very successful at implementation. Unlike in New Zealand, public policy transforms from idea to action quickly and efficiently. Public policy and strategy in Bhutan is guided by a coordinated long-term vision (including the pillars of Gross National Happiness), which means different political parties are working towards the same objectives.

Learning from Bhutan: Our top ten policy ideas for New Zealand in 2023

1. Ecological corridors –

a tool to protect biodiversity, capture carbon and mitigate the impacts of climate change

Ecological corridors (also known as biological or wildlife corridors) act as ‘green belts’, and are protected areas designed to connect species habitats (or other conservation areas, such as reserves or national parks). The corridors allow species to travel freely between areas. They improve habitats, protect species and their ecosystems from the impacts of climate change, mitigate against biodiversity loss, and allow native flora and fauna to thrive. Ecological corridors also act as a carbon sink, benefiting the world as native forests absorb carbon and purify the air we breathe.

In New Zealand, the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions removed by forest land each year between 1990 and 2020 ranged from 19.1 million tonnes (in 2019) to 36.4 million tonnes (in 2007).[13] Bhutan is a world leader in this concept, with the country’s forested areas already connected through a network of ecological corridors.

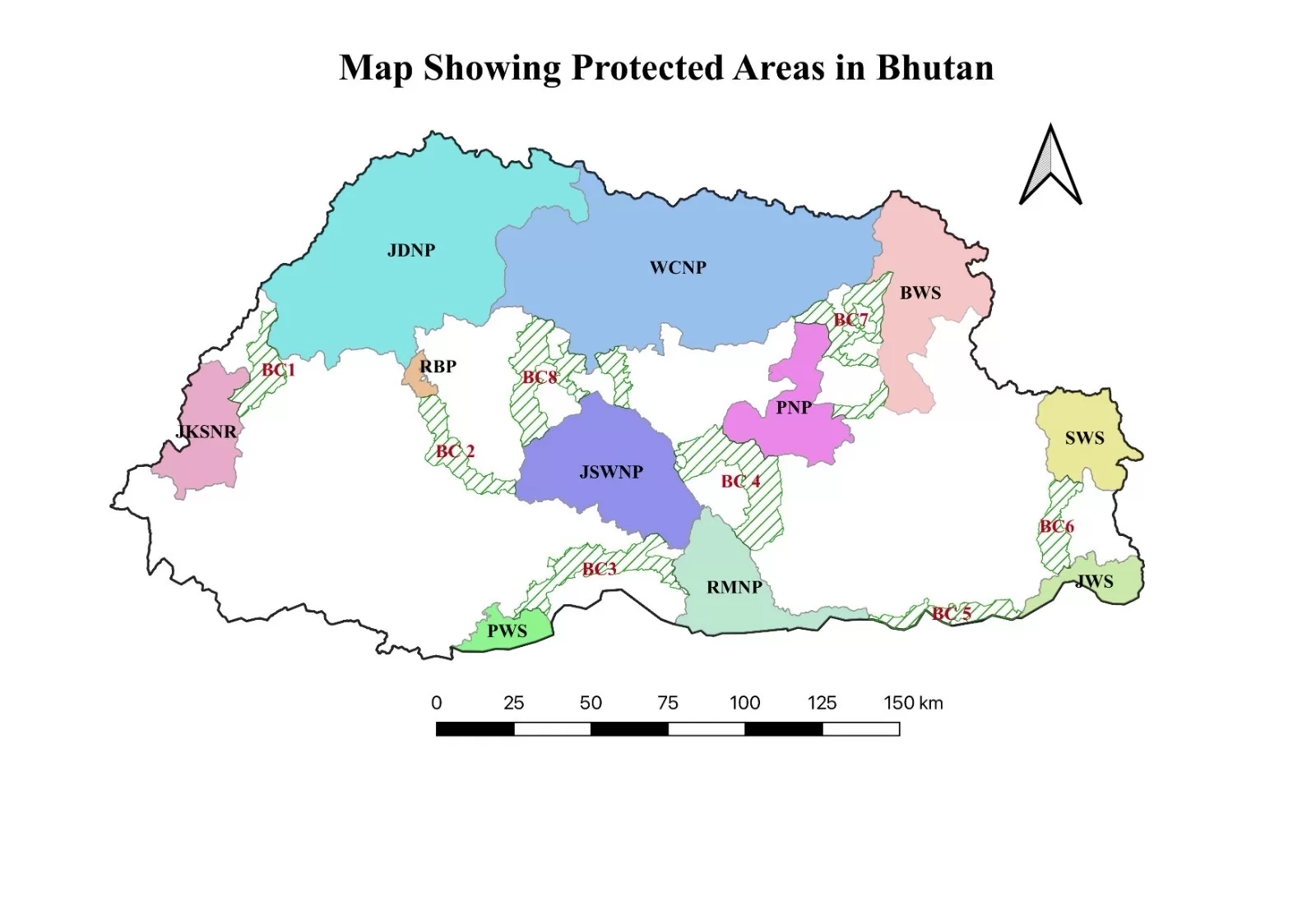

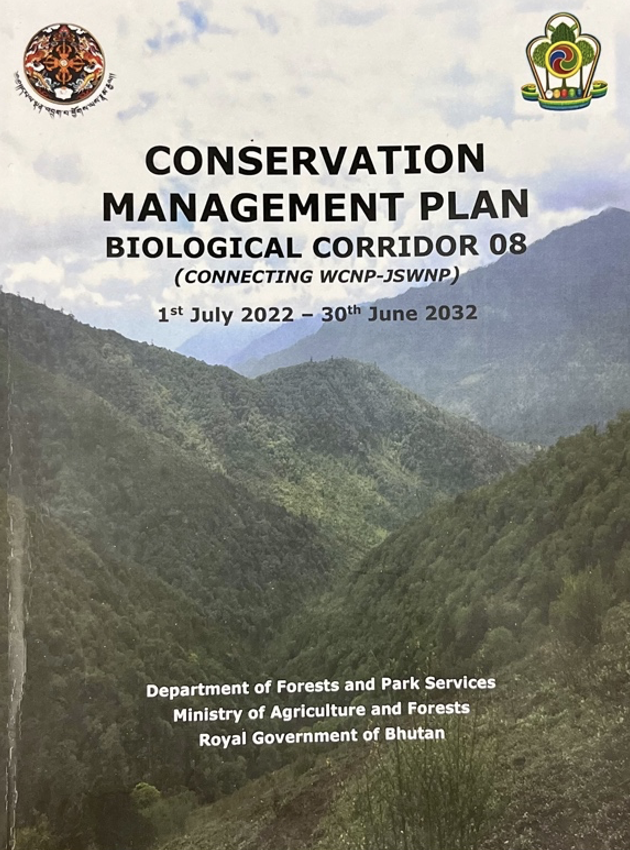

Presently, Bhutan is home to five national parks, four wildlife sanctuaries, one nature reserve and nine biological corridors. There is also work being undertaken to create an additional tenth corridor which would connect Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary with Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, as can be seen in the map on the right. These corridors are part of why Bhutan is considered a ‘global biodiversity hotspot’[14] and has become a leading destination for eco-tourism.

Bhutan’s protected areas and biological corridors

This map shows Bhutan’s National Parks (assorted block colours), connected by ecological corridors (striped green). Map source: Nature Conservation Division, Department for Forests and Park Services. (2023). Map Showing Protected Areas in Bhutan. Retrieved August 5 2023.

Implications for New Zealand

Ecological corridors have been a strong focus of the Institute’s climate change work, and though we have been investigating the idea since 2018, we wanted more detailed information on how they are designed, operated and maintained. Our meetings with conservation and government organisations confirmed Bhutan’s corridors are not only a strong idea, they are also extraordinarily successful in practice. Forestry experts we met reported the corridors have allowed species (such as tigers and leopards, as can be seen in this video footage)[15] to travel between protected nature areas, while also protecting ecosystems by promoting genetic diversity, helping make flora and fauna more resilient to climate change and extreme weather. Our meetings were invaluable to learning how corridors operate in practice, and to understand how they could be implemented within New Zealand.

Ecological corridors are effective when they connect national parks and large reserves. In New Zealand this could begin with stewardship land along the West Coast of the South Island, which currently remains under review by the Department of Conservation (DOC).[16] The carbon-absorbing properties of ecological corridors would also make them an effective new mechanism for carbon credits based on native rather than exotic forestry. This is an idea the Institute will explore further, with a possible proposal to COP which could include other countries like Canada and Australia. This is a big idea and one that may enable New Zealand to reduce our carbon credit deficit in 2030. The need to reduce New Zealand’s carbon debt by 2050 is discussed in the Institute’s Discussion Paper 2021/04 – An Accounting Dilemma: Does a commitment to purchase offshore carbon credits create a requirement to disclose that obligation in the financial statements of the New Zealand Government?.

Getting a network of ecological corridors into New Zealand is a really exciting project and the Institute is currently developing a working paper on this idea, using Bhutan as a case study along with a corridor system being developed in Canada. You can follow the Institute’s research on ecological corridors on our website under EcologicalCorridorsNZ.

The Constitution of Bhutan provides a high level of protection for the environment and assigns every citizen a role as trustee of the country’s natural resources. It also gives Parliament the power to declare any part of the country a national park, wildlife reserve, protected forest, biosphere reserve, critical watershed or any other category protecting the environment. This long-term approach to environmental protection and conservation strategy is another area where New Zealand, and the rest of the world, can learn from Bhutan.

Bhutan’s Constitution was written in 2008, making it one of the newest constitutions in the world, and it is interesting to see how it was written compared to New Zealand’s much older Constitution Act of 1986. With the benefit of foresight, Bhutan has been able to research other countries’ constitutions and imitate what works well. The country has incorporated constitutional elements from the UK, USA and India while incorporating its own distinctive Bhutanese and Buddhist elements.

Constitution of Bhutan 2008

Article 5: Environment

- Every Bhutanese is a trustee of the Kingdom’s natural resources and environment for the benefit of the present and future generations and it is the fundamental duty of every citizen to contribute to the protection of the natural environment, conservation of the rich biodiversity of Bhutan and prevention of all forms of ecological degradation including noise, visual and physical pollution through the adoption and support of environment friendly practices and policies.

- The Royal Government shall:

- Protect, conserve and improve the pristine environment and safeguard the biodiversity of the country;

- Prevent pollution and ecological degradation;

- Secure ecologically balanced sustainable development while promoting justifiable economic and social development; and

- Ensure a safe and healthy environment.

- The Government shall ensure that, in order to conserve the country’s natural resources and to prevent degradation of the ecosystem, a minimum of sixty percent of Bhutan’s total land shall be maintained under forest cover for all time.

- Parliament may enact environmental legislation to ensure sustainable use of natural resources and maintain intergenerational equity and reaffirm the sovereign rights of the State over its own biological resources.

- Parliament may, by law, declare any part of the country to be a National Park, Wildlife Reserve, Nature Reserve, Protected Forest, Biosphere Reserve, Critical Watershed and such other categories meriting protection.[17]

Implications for New Zealand

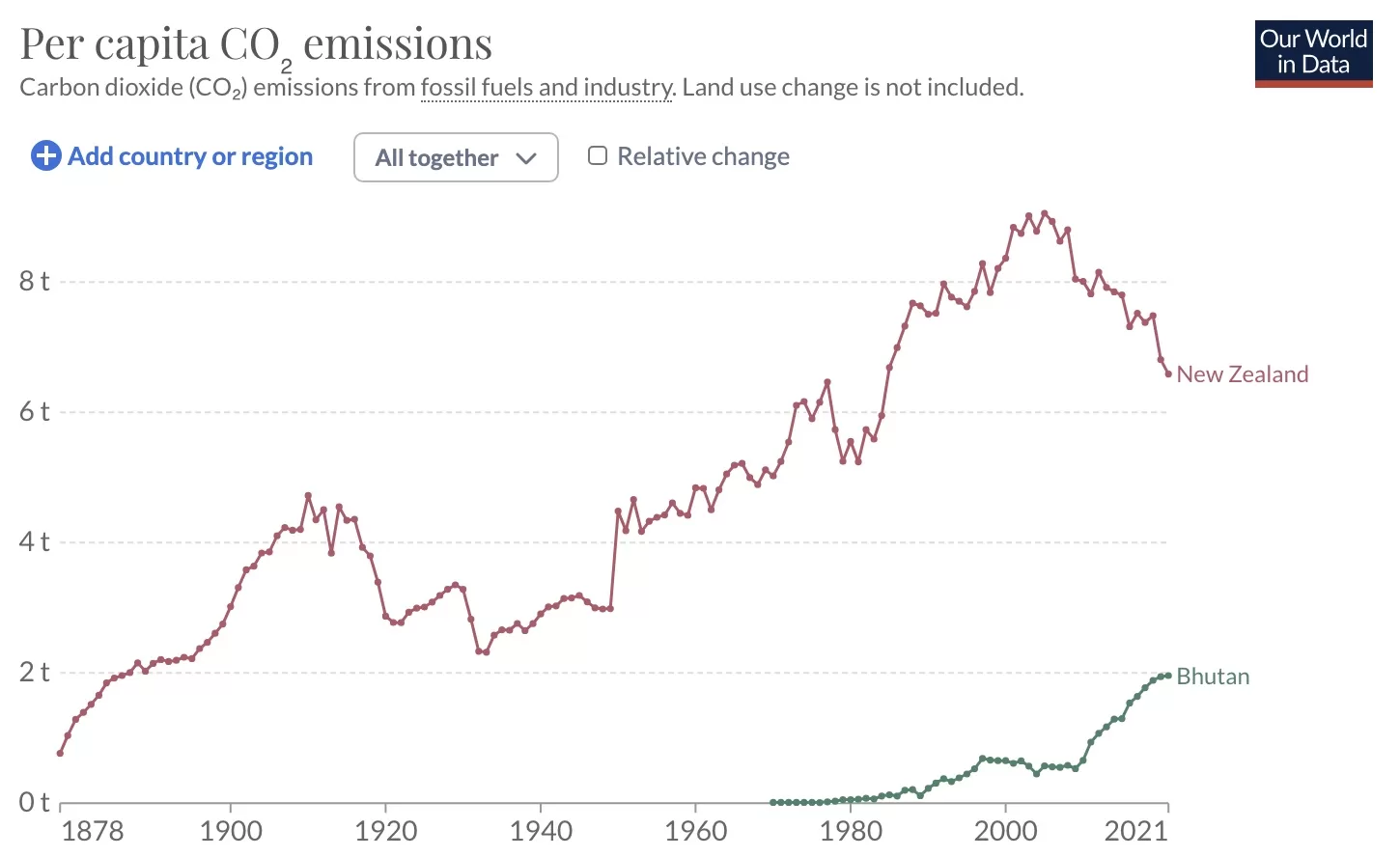

In comparison to Bhutan, New Zealand’s gross greenhouse gas emissions are, per capita, the 22nd-highest in the world,[21] with our total emissions continuing to increase (refer to graph to the right) despite international commitments to the contrary.[22] Our Protected Areas Network is estimated to cover a little over 30% of our land area, with legally protected marine reserves estimated to cover only 7% of our territorial sea.[23]

New Zealand’s extremely low level of protection for our biodiversity is of local and global concern, with our country reporting the world’s highest proportion of species at risk.[24] These species are vital parts of our ecosystems and once they are lost, we cannot get them back. The urgency of the biodiversity crisis was reinforced in December 2022, when the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (of which New Zealand is a member) committed to protecting 30% of land and ocean by 2030.[25] This gives our country only seven years to more than quadruple our amount of marine protected areas, and progress in 2023 has stalled as parties struggle to agree on methods of implementation.[26] This issue links into the Institute’s OneOceanNZ project, and to our work on aquaculture strategy in New Zealand.

It would be great to see New Zealand adopt a long-term, Bhutanese-style approach to environmental protection and conservation, particularly in the marine space. Bhutan’s megafauna are land-based, including tigers and leopards, and New Zealand’s megafauna are ocean-based, including whales and other marine mammals. Protecting the land and the sea for future generations also aligns with the Māori value of kaitiakitanga, or guardianship. With a constitutionally coordinated approach, all political parties and other stakeholders would more likely work together and deliver better long-term outcomes.

This graph compares annual emissions per person in New Zealand (red) and Bhutan (green).

Graph source: Our World in Data (2022). Using data from Global Carbon Budget (2022); Gapminder (2022); UN (2022); HYDE (2017); Gapminder (Systema Globalis). Retrieved 2 August 2023 from OurWorldInData.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions

Since Bhutan opened up to tourists in the 1970s, its tourism strategy has always been to attract a low quantity of high-value visitors. The country has focused on developing a reputation as one of the most exclusive travel destinations in the world while working to protect Bhutanese communities and the environment from the impacts of mass tourism. As part of this strategy, Bhutan has implemented a Sustainable Development Fee (SDF) for all international tourists. However, even with this fee in place, visitor numbers in the 2000s increased to overwhelming amounts, and the community began to suffer from the impacts of mass tourism (including increased waste, environmental degradation and negative impacts on local culture).

When the country decided to reopen to tourism post-COVID, it was seen as an opportunity to reset the tourism industry. This started by significantly increasing the SDF (from US$65 to US$200 per person per day) and was combined with a stylish rebrand and new tagline, ‘Believe.’[27] Dr. Tandi Dorji, Bhutan’s foreign minister and chairman of the Tourism Council of Bhutan, said, ‘COVID-19 has allowed us to reset, to rethink how the sector can be best structured and operated, so that it not only benefits Bhutan economically, but socially as well, while keeping carbon footprints low … in the long run, our goal is to create high-value experiences for visitors, and well-paying and professional jobs for our citizens … The priority is for Bhutan to preserve its culture and way of life. If we have to sacrifice tourism, so be it.’[28]

In June 2023, the Bhutanese Government amended the SDF to encourage longer stays and boost visitor numbers post-COVID. From June, visitors who pay the daily US$200 fee for the first four nights of their trip do not need to pay for the next four days. Visitors paying the SDF for 12 days can stay the full month.[29] Visitors from neighbouring India will continue to pay their far lower rate of 1,200 rupees (almost US$15) per night, which has not changed. This update to the country’s tourism strategy is an example of Bhutan designing policy for the long term, balancing economic development with other GNH pillars to benefit the whole community. ‘Tourism is like minerals, to be protected for the future generation. The present generation might have to make sacrifices and lose some of our business in the short term, but in the long run, we all benefit,’ said Mr Dorji.[30]

Bhutan says money collected from the SDF is used for ‘investment in transformative programmes that sustain our cultural traditions, protect our environment, upgrade infrastructure, and build our resilience. Critically, it supports the development of training, mentorships and further education that will create long-term opportunities for our young people.’[31] The SDF income also contributes to free healthcare and education for all citizens.[32] If patients cannot be treated in Bhutan, the Government pays for them to be sent for treatment at hospitals in India.

In conversation with Bhutanese people, many expressed gratitude for policies that have allowed them to enjoy their quiet and peaceful country. Lower volumes of tourists means Bhutan’s unique culture has been preserved and the country has avoided issues of mass tourism, many of which are evident in nearby countries like Nepal. Bhutan’s conservation work also benefited the country’s international reputation, growing eco-tourism industry and glowing media coverage (for instance the March 2023 Tatler travel essay titled ‘Why Bhutan – home to one of the world’s most intriguing royal families – is the last Shangri-La’).[33] Bhutan has carefully marketed itself as a progressive and sustainable Himalayan kingdom, with former Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay’s 2016 TED talk on the country’s policy credentials receiving an impressive five million views.[34]

Implications for New Zealand

Despite being a major part of New Zealand’s economy, our tourism industry has received criticism from private and public sectors for its fractured strategy. Our experience in Bhutan suggests New Zealand would benefit from adopting a similar high-value, low-volume policy with a tourism fee. International tourists enjoy New Zealand’s beautifully conserved public areas, use (clean and modern) public toilet systems, and throw their rubbish in well-maintained waste management systems. All of this costs money to build and maintain. Requiring tourists to pay an upfront fee for these costs will not only mean New Zealanders do not have to cover costs created by tourists, but will also enable us to ensure our public systems remain world-class while protecting the environment.

Low-volume strategies are sustainable: they minimise carbon emissions from mass tourism, promote eco-tourism and luxury travel, and mitigate issues like environmental degradation and overcrowding. Our research suggests a successful tourist fee in the New Zealand context may not look the same as that in Bhutan. For instance, New Zealand may benefit from a smaller fee which has a set time limit (e.g. only applies for the first two weeks to encourage longer stays), has exceptions (e.g. does not apply to Australian citizens) and is more affordable (e.g. NZ$35–40 per day). Like Bhutan, New Zealand is already attractive to high-value tourists, and these tourists tend to be wealthier and stay for longer due to the time and expense it already takes to get here. A fee is unlikely to deter these tourists, and will also work to enhance the country’s ‘100% pure’ clean and green image. Protecting New Zealand’s reputation for sustainability and our untouched natural environment will be beneficial for both our tourism and export industries.

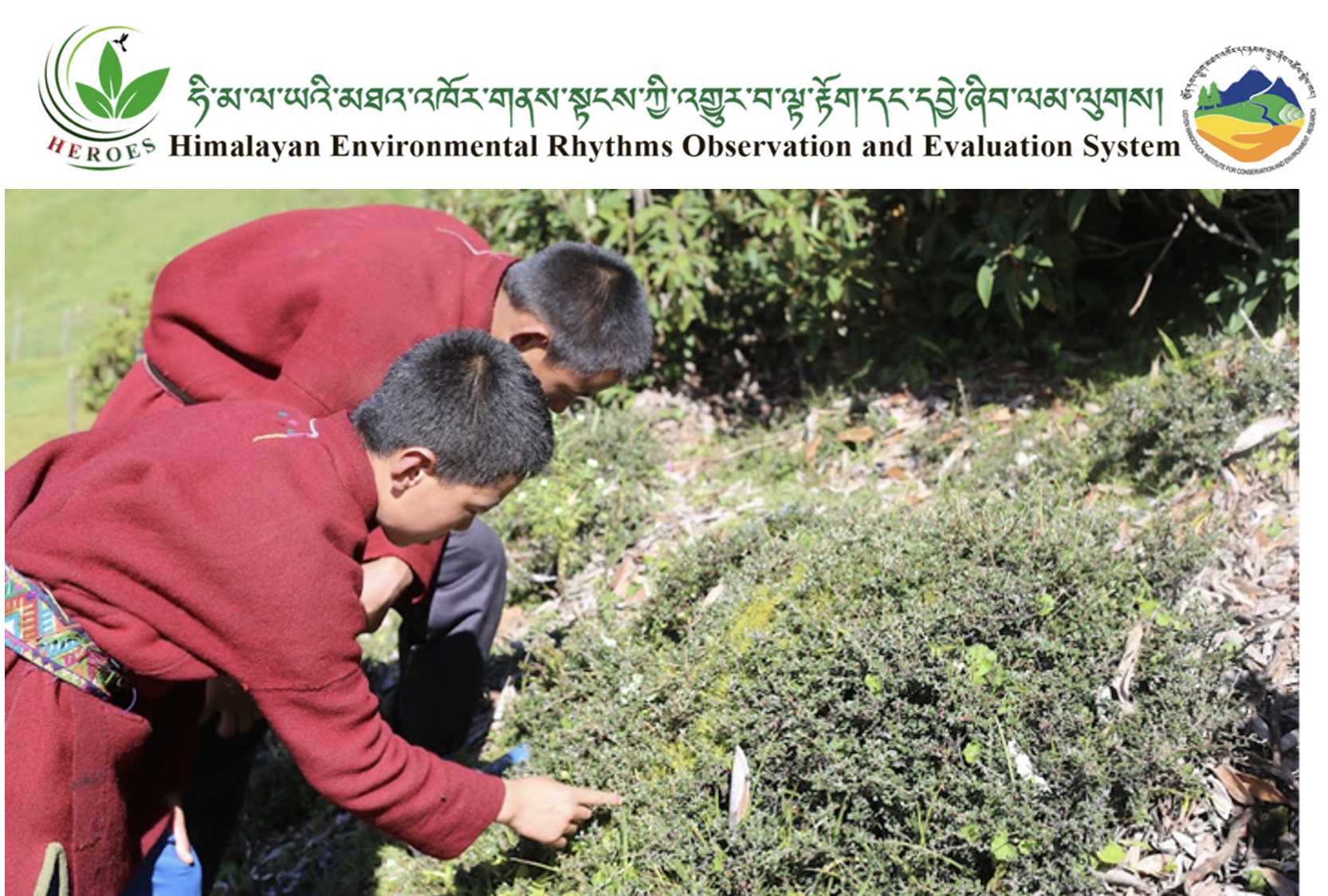

The Himalayan Environmental Rhythms Observation and Evaluation System (HEROES) Programme is a Bhutanese youth science programme which we believe could be replicated to great success in New Zealand. We learned about this programme when we visited UWICER and met with Sangay Tiger. The programme started in 2014 as a way to both educate young generations about the environment and generate high-quality scientific data. In the programme, school students observe weather patterns and plant species, taking note of changes that occur. These observations are then compared with different years as a way of observing the impact climate change has on the weather and flora and fauna.

The aim is to gather environmental data and understand the impacts of climate change on weather and native biodiversity. The HEROES programme has generated high-quality data on climate change impacts in 20 cities and on the yearly life-cycles of 110 plant species. Over 400 students are involved each year, recording 2.8 million observations.[35] This climate data is then also available for public use, and can be accessed by anyone on the HEROES website.

Implications for New Zealand

A lack of baseline environmental data is a consistent issue that has come up in the Institute’s research and work on conservation in New Zealand, particularly in terms of marine environments. As is commonly said by scientists, we cannot protect what we do not know. The more information we have on our native species and their habitats, the better placed we are to make conservation, planning and management decisions to protect the environment for future generations.

Implementing a local version of the HEROES programme would help gather quality data on biodiversity and climate change in New Zealand. The programme could start small and expand across schools as its systems improve. The data can then be used to make educated environmental management decisions and feed into conservation policy. Engaging school groups to become invested in gathering data not only educates youth on how to make data-driven decisions, but also promotes awareness of the environment and inspires young people to get involved in responding to climate change and protecting biodiversity.

Developing responsible future citizens should be an important part of every country’s strategy for the future. We think implementation of a programme similar to HEROES in New Zealand is a relatively simple policy idea which achieves benefits for education, conservation, science and the community.

Constitution of Bhutan 2008

Article 9: Principles of State Policy

1. The State shall endeavour to apply the Principles of State Policy set out in this Article to ensure a good quality of life for the people of Bhutan in a progressive and prosperous country that is comitted to peace andamity in the world.

2. The State shall strive to promote those conditions that will enable the pursuit of Gross National Happiness.[37]

Everyone who enters the Centre for Bhutan & GNH Studies must pass under a grand entrance gate which aptly states it is the ‘Gateway of Intellect’. On the day we arrived, we were suprised to find the large building filled with empty desks. When we asked Mr Karma Wangdi where the majority of his colleagues were, he confirmed they were out on the field. The process of surveying the population is comprehensive and resource-intensive. In 2023, it was reported the GNH index had interviewed a total of 11,052 respondents (aged 15 and above), representing a geographical spread across 198 gewogs (village clusters) and 53 towns.[38] Collecting this data took four months (from April to August), with each interview conducted in person and lasting approximately an hour and 45 minutes.[39]

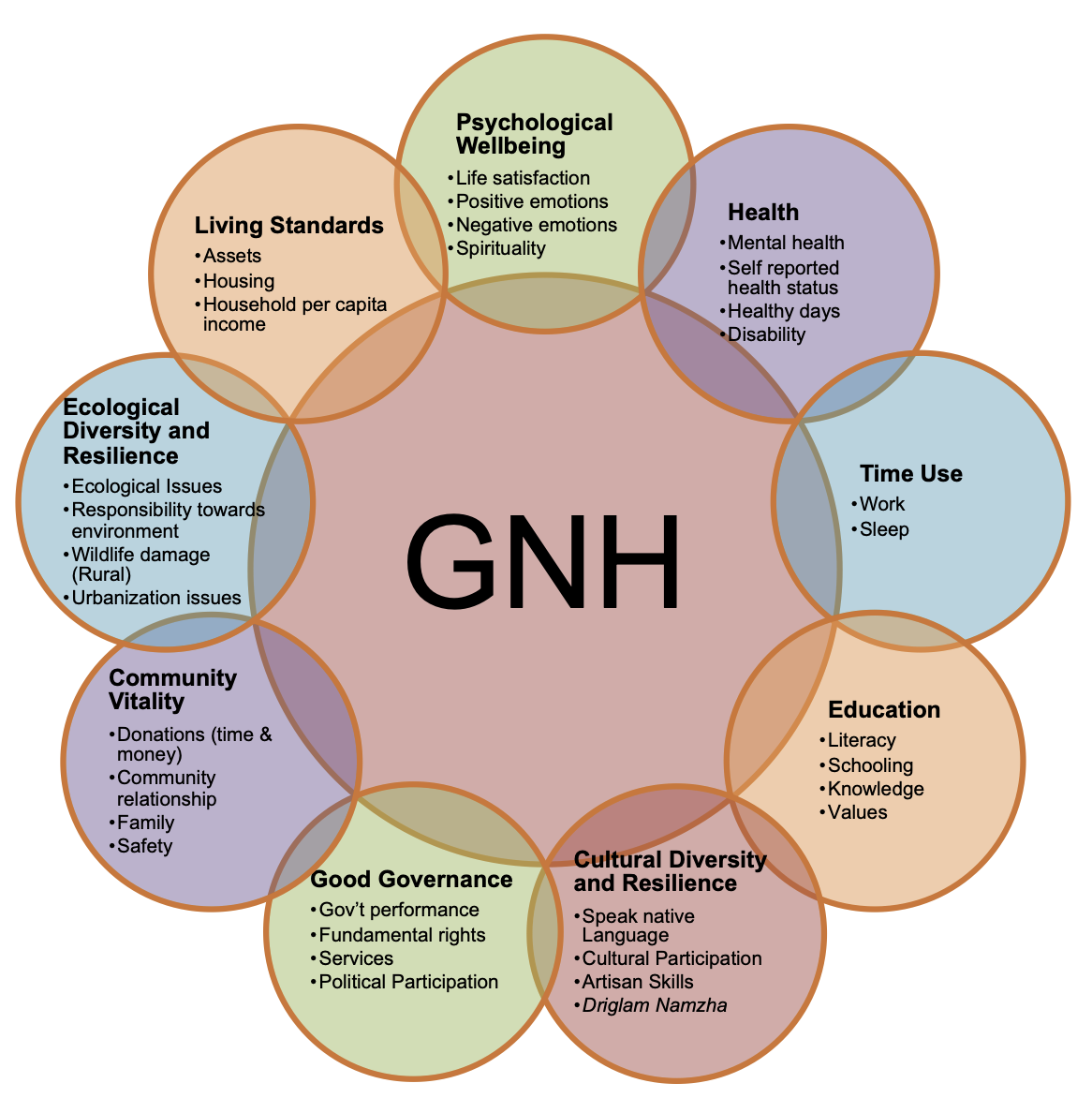

GNH is measured by an index, which is designed to calculate the collective happiness and wellbeing of the entire population. The GNH index calculates happiness based on nine domains, which can be seen in the diagram to the right. The index determines that collective ‘happiness’ is achieved when these are balanced. This strategy is strongly influenced by Buddhism, particularly the Buddhist concept of the ‘Middle Way,’ where ‘happiness is accrued from a balanced act rather than from an extreme approach’.[40]

These four pillars reflect the Buddhist values of peace, non-violence, tolerance and compassion.[41] The GNH encompasses 33 weighted indicators across nine domains which include psychological well-being, health, time use, education, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards. Before any strategy, policy or project is implemented in Bhutan, it must have a GNH check (called the GNH ‘Policy Lens’), where it is assessed to make sure it benefits GNH. If a strategy, policy or project is not beneficial to GNH (for instance it harms the environment, or will degrade the culture), it will not be implemented.

Bhutan’s GNH is measured by a nationwide survey, which is currently undertaken every five years. The Government then uses the results of the GNH to flow directly into the country’s five-year strategic plan. The public budget is also allocated according to the results of the GNH survey, with more resources given to areas that score lower. For instance, if rural health scores low, the Government will allocate more funding to healthcare in those areas. The effects of proposed policies are then measured by the results of the next GNH index, which tracks over time where intervention is needed. We especially admired this evolutionary aspect of the GNH survey. As indicators are met, they are removed and replaced, so the GNH is constantly evolving as society changes.

GNH is believed to produce a more balanced perspective on development than GDP because it incorporates social, environmental, cultural and political factors rather than just economic ones. GNH is also different because each indicator has an allocated maximum value, wheras GDP can continue to grow exponentially. For instance, once an income or sleep indicator is met under a GNH survey (set at 1.5 times the country’s poverty line and 8 hours respectively),[42] that indicator will be removed from the index and replaced with something else. This means the GNH index will prioritise meeting universal basic needs for all, rather than GDP, which focuses on continually producing greater output (which may only benefit a few and cause other issues not accounted for, such as environmental degradation).

Implications for New Zealand

The idea of replacing, or supplementing, GDP with a more comprehensive measurement system is not a novel idea for New Zealand. In 2018, the New Zealand Treasury first implemented our own Living Standards Framework (LSF) Dashboard, which ‘provides the indicators that the Treasury believes are most important to inform our wellbeing reporting and our policy advice on cross-government wellbeing priorities’.[43] However, Bhutan’s framework holds a much higher significance in policy-making, and it is clear that this has had beneficial outcomes for the people and environment in Bhutan. We think New Zealand could work further to pursue a similar strategy, putting wellbeing, rather than economics, at the heart of every public policy decision.

In Bhutan, GNH is a significant driver of policy and strategic planning. Once a survey is completed, new policies and strategy are implemented to reflect the results of the strategy. Bhutan’s policies on GNH are also a great example of quick and effective implementation. Policy responds directly to issues raised in the GNH, and New Zealand policy could also benefit from a more responsive approach.

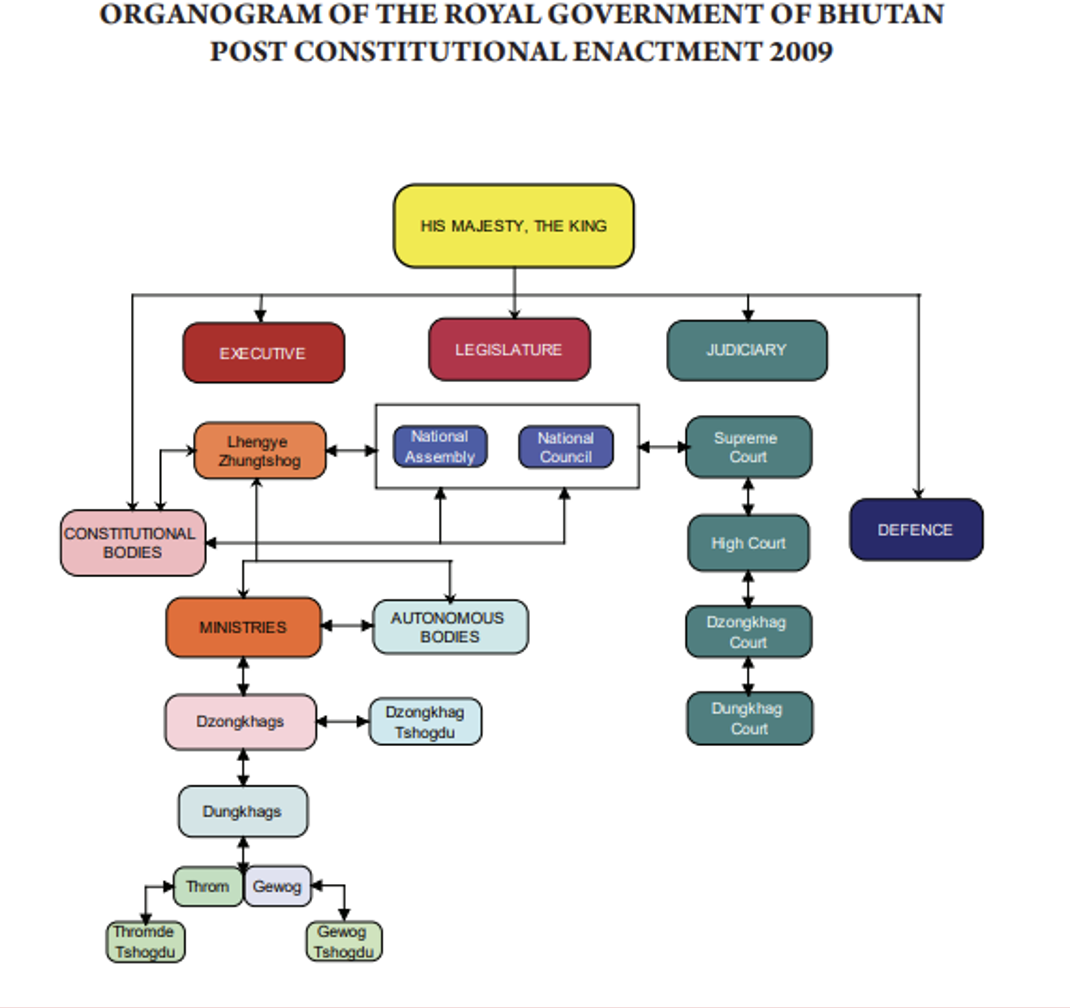

The Bhutanese parliamentary system:

- The King of Bhutan is the Head of State.

- The Prime Minister is the Head of the council of ministers (or Lhengye Zhungtshog) and has executive power.

- Parliament is made up of 72 democratically elected members. It consists of the King of Bhutan, the National Council (lower house) and the National Assembly (upper house). It is the highest legislative institution in the country. Bhutan’s Parliament is bicameral and follows Westminster Parliamentary systems.[44]

- The National Assembly (lower house) is made up of 47 democratically elected members, all of whom are elected from 47 constituencies in the country and belong to either the ruling or opposition parties. The National Assembly selects the Prime Minister.

- The National Council (upper house) is made up of 25 members, including 20 democratically elected representatives (one per district), plus another five appointed by the King as eminent persons. The Council is non-partisan and, apart from its legislative mandate, it is the house of review.[45]

Constitution of Bhutan 2008

Article 22: Local Governments

1. Power and authority shall be decentralized and devolved to elected Local Governments to facilitate the direct participation of the people in the development and management of their own social, economic and environmental well-being.

…

17. A candidate or member of the Local Governments shall not belong to any political party.[46]

Implications for New Zealand

Integrating non-partisan local-government members into the Parliamentary system in this way means long-term strategy can be achieved at a local level. This would be beneficial to New Zealand because when leaders are not aligned with a specific political party, the focus is on making decisions for the common good. This produces a more coordinated political environment, working to design the best possible policy for the country rather than focusing on political ideology.

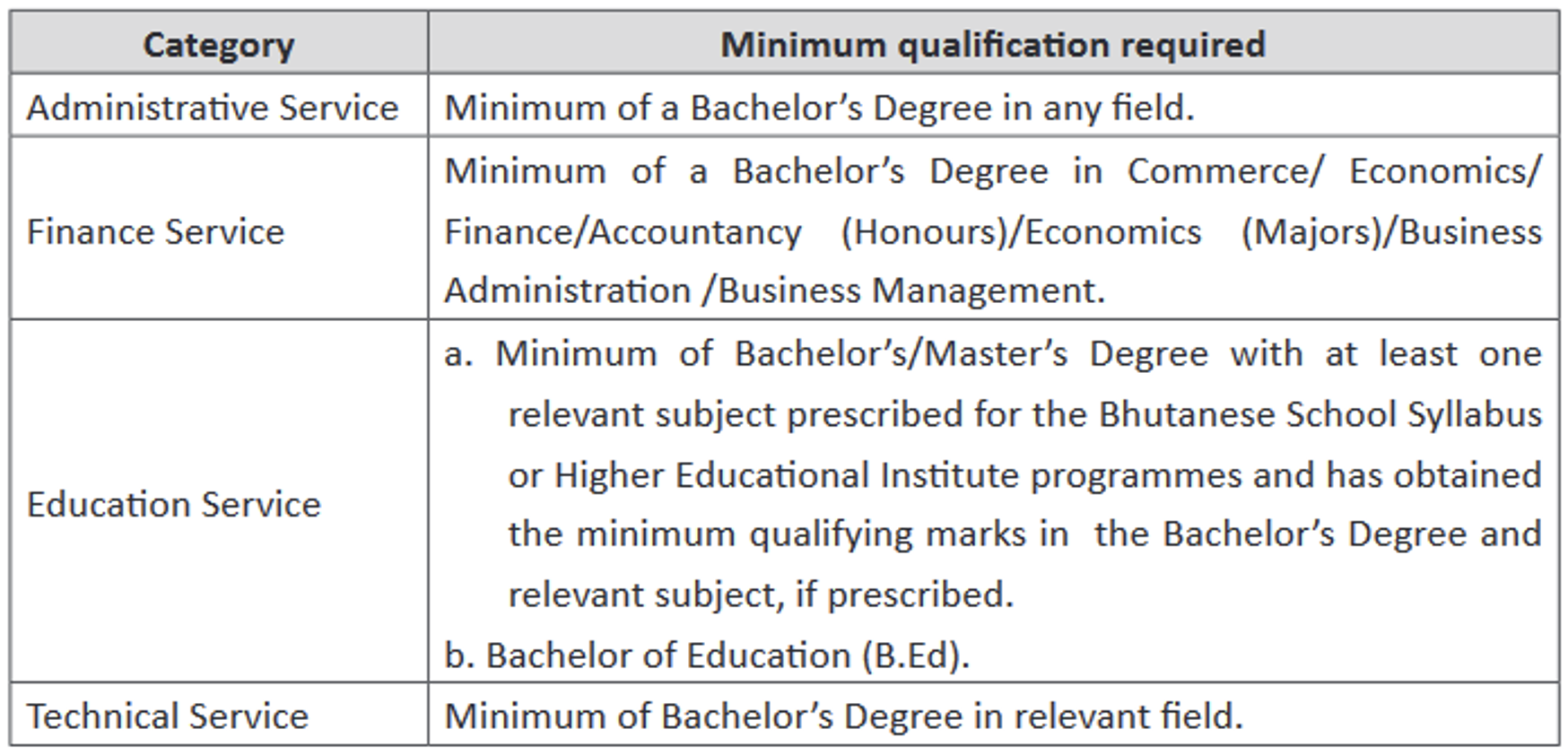

Royal Civil Service Commission Eligibility Criteria

1. Be a Bhutanese citizen; 2. Have attained at least 18 years and not be older than 35 years for pre-service and 45 years for in-service candidates, as on the last date of online registration; 3. Have a minimum of Bachelor’s Degree (full time on campus course meeting the requirement of the minimum contact hours) for minimum duration of three years from an Institute recognised by the competent authorities in the relevant field with an exception for the following: a. Candidates from Shedras who are awarded equivalent Bachelor’s/Master’s Degree in two years.

b. With a minimum two-year Bachelor’s Degree acquired by in-service candidates with minimum of Class X and Certificate/Diploma of two years or more, if duly validated by the Royal University of Bhutan/Bhutan Accreditation Council/Bhutan Medical and Health Council and other competent authorities empowered by an Act of the Parliament, for in-service candidates.

c. With Master’s Degree but without Bachelor’s Degree approved by the RCSC for in-service candidates prior to 2nd September, 2007.

4. Meet the following qualification and subject requirements:

Implications for New Zealand

Bhutan has a civil service system carefully designed to attract and retain the best talent in the country. As can be seen by the high number of applicants each year, getting a civil service job is highly competitive and respected in the community. This means that highly motivated and educated individuals join the government sector in Bhutan. This group works together to design and implement public policy. The implications of this are a system which is world-leading, efficient and innovative.

In comparison, public sector jobs in New Zealand are often second-best to private sector jobs, which can offer higher pay and greater flexibility. Getting a civil service job is not as competitive and it is harder to attract and retain talent for public sector roles. Attracting and retaining a greater number of educated, motivated people in the public sector could have significantly positive results for the community. A civil service set of exams would also benefit New Zealand by ensuring all public servants understand the requirements and purpose of their role. Recent issues in New Zealand politics, such as politicians failing to disclose conflicts of interests,[49][50] suggests that an examination with clear guidelines for public servants would be beneficial. Politicans and others in governance roles have a significant responsibility to the public and their eligibility criteria should reflect this.

Earlier in 2023, Bhutan made global headlines as its seven-year-old crown prince became the country’s first official digital citizen.[51] In June 2023, Bhutan unanimously passed a National Identity Bill to enable the rollout of that same digital ID across the population. This Bill has been designed to establish an inclusive and equitable framework for the country’s national ID system. It is an international first as it means upon receiving a digital identity, individuals can access services like obtaining passports or legal agreements through a mobile application called a Digital Wallet.[52] This Digital Wallet system not only removes the need for paperwork, it also increases efficiency, security and privacy.

The Bill is a part of the self sovereign model, where people can get access to their own decentralized verified information on their phones through their personal Digital Wallet. Through the user-friendly Digital Wallet, people can also do transactions online without having to authorize a third party. The system has been especially designed to improve transparency and trust in Bhutan’s digital identity system. Improving digital accessibility is a major goal of this policy, including trialling a scheme to send support workers to a village twice a month with mobile devices, laptops and an internet connection to help people access their Digital Wallet.[53]

The Bhutanese Government has promised the Bill and its corresponding digital initiatives will be inclusive, responding to concerns about accessibility for persons with disabilities.[54] The Government has confirmed it will ensure the Bill has been designed to cater to diverse individual needs with a number of inclusive features, including:

- Assistive technologies (designed for impaired abilities by integrating with screen readers).

- User-friendly interfaces (clear instructions, visual aids and simple design).

- Multilingual support (reflecting over twenty languages are spoken across Bhutan).[55]

- Accessibility standards (committing to comply with international guidelines and following best practice).[56]

Implications for New Zealand

New Zealand also recently (in March 2023) passed our own Digital Identity Services Trust Framework Bill. This Bill was designed to make it easier for New Zealanders to prove who they are digitally.[57] There were concerns the digital environment in New Zealand lacked consistent standards and this Bill has also been designed to improve trust and accountability. However unlike Bhutan, the updated New Zealand framework has largely been designed to ensure digital service providers can prove digital identity, allowing them to opt-in to receiving an accredited businesses a ‘trust mark’ if they wish.

Whilst New Zealand does have legislation and frameworks in place to protect digital identity, in comparison to Bhutan there is not as much protection on an individual level. For instance, passports and drivers licenses are still required to be hard copies, whereas in Bhutan the Digital Wallet acts as a form of personal identification. The Bhutanese framework has also been carefully designed to be inclusive and equitable, something which all countries, including New Zealand, should incorporate into policy. This issue is especially important in the digital age, as technology is an area where people are often left behind.

This policy fits into both the Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan and Bhutan’s most recent Five-Year Development Plan.

Constitution of Bhutan 2008

Article 5: Environment

1. Every Bhutanese is a trustee of the Kingdom’s natural resources and environment for the benefit of the present and future generations and it is the fundamental duty of every citizen to contribute to the protection of the natural environment, conservation of the rich biodiversity of Bhutan and prevention of all forms of ecological degradation including noise, visual and physical pollution through the adoption and support of environment friendly practices and policies.[60]

Bhutan’s 12th Five-Year Development Plan 2019–2023

Effective waste management is identified as a major emerging issue threatening both public health and pristine environment. According to Bhutan’s second National Communication to the UNFCCC, emissions from waste increased by 247.45 percent from 0.047 in 2000 to 0.16 million tons of CO2e in 2013. The common solid waste management practice is dumping in landfill sites and waste segregation and recycling are minimal. Hence, the NECS in consultation with relevant stakeholders will develop national and Thromde level waste management strategy.[61]

Implications for New Zealand

New Zealand is one of the highest generators of waste per capita in the world, every year producing about 750kg per person.[62] In 2023, the Government announced a recycling project aiming to prevent the equivalent of approximately 45,000 tonnes of carbon emissions by 2035 and to make New Zealand a low-emissions, low-waste circular economy by 2050.[63] The initiative also aims to have a standardised recycling service by 2027 and food scraps collection by 2030.[64] The legislation to support this strategy is to be ‘progressed during the next Parliamentary term’, which demonstrates the potential issues with New Zealand’s short-term strategy. Unlike Bhutan, which has a Five-Year and Ten-Year Plan to design strategy, New Zealand has to operate on a three-year election cycle. This makes it difficult for central and local government to coordinate long-term planning.

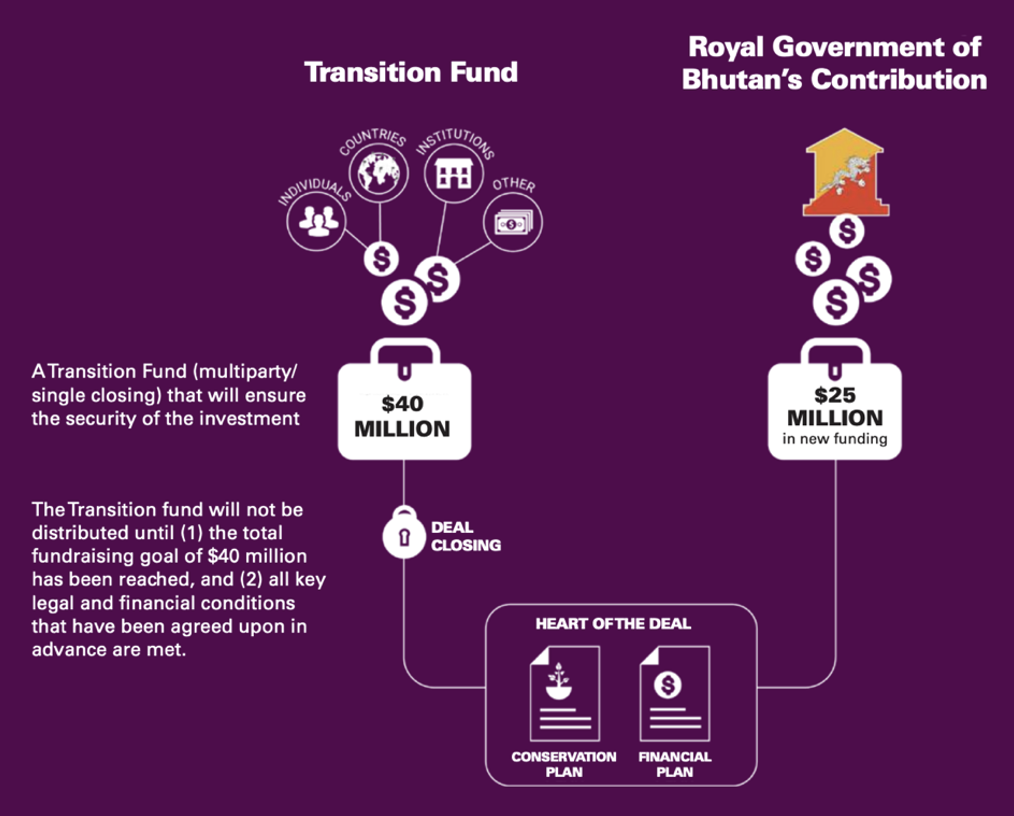

10. Bhutan for Life (BFL) –

a new funding strategy

BFL is a forward-thinking funding mechanism designed to provide a sustained flow of finance to maintain forests and protected networks. Started in 2018 to permanently protect Bhutan’s network of protected areas, which contribute to human wellbeing and biodiversity conservation, and improve resilience to effects of climate change, BFL is Asia’s first Project Finance for Permanence model.[65]

BFL is unique because it incorporates foreign investment and philanthropy into environmental management, with the eventual goal that Bhutan will cover these costs without foreign assistance.[66] The funding from the BFL model has been used for biodiversity conservation, species monitoring, habitat protection, developing ecological corridors and national parks, community education, waste management and working to promote gender equity.

Implications for New Zealand

New Zealand currently has a number of conservation and community projects designed to protect the environment and mitigate the impacts of climate change. However, local funding is often lacking, which means projects are not implemented. Unlike Bhutan, New Zealand does not utilise innovative combinations of public and international funding mechanisms for such projects. BFL is a funding alternative which allows a country to invest in conservation, even if it does not currently have all the funding required.

A New Zealand transition funding mechanism would allow large-scale conservation schemes (such as ecological corridors) to be implemented now, rather than sitting on the shelf until enough public funding is received. Starting conservation schemes as soon as possible will help New Zealand to meet its international commitments such as the Paris Agreement. If New Zealand is to achieve its international commitment to reduce net emissions by 50 percent by 2030[67] (currently under seven years), large-scale projects to reduce and absorb carbon must begin now. Bhutan is a great example of implementing projects quickly and effectively, which could make a significant impact on New Zealand’s carbon emissions. As the Chinese proverb says, ‘The best time to plant a tree was yesterday. The second best time is now.’

Source: Bhutan for Life. (2018). Bhutan For Life Prospectus. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from www.bhutantrustfund.bt/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Bhutan-For-Life-Prospectus-BFL.pdf

What Bhutan and New Zealand can learn from one another

Although Bhutan is internationally recognised for innovative public policy and strategy, Bhutanese are the first to admit it is not a ‘Shangri-La’ (a remote paradise of perfection), despite what some media articles may claim. Even former Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay said in 2013 that ‘Bhutan’s much lauded concept of Gross National Happiness is overused and masks real problems such as increasing debt, chronic unemployment, poverty and corruption.’[68]

Many of the people we spoke to shared concerns about large numbers of educated youth moving overseas, largely to Australia, which is attractive as it has a large Bhutanese community and comparatively high incomes. Young Bhutanese leave in search of better jobs and opportunities, and there are concerns about how many will return. Another important consideration is Bhutan’s reliance on importing goods and services from nearby countries, creating a supply chain risk for essentials such as food.

Bhutan’s relationship with neighbouring India (the country’s largest trading partner) extends into hydroelectricity. In April 2014, the countries signed the Framework Inter-Governmental Agreement for development of Joint Venture Hydropower Projects through the Public Sector Undertakings of both countries.[69] Post-COVID, New Zealand has also needed to reassess our own supply chain risks, with physical remoteness and increasing costs exposing the fragility of our trade networks.

Our conversations with people and organisations confirmed that despite differences on the surface, Bhutan is facing many of the same issues as New Zealand. One especially inspiring meeting was with staff from the Druk Journal and the Bhutan Centre of Media and Democracy (BCMD) in Thimphu. The Druk Journal, a non-partisan publication, was formed eight years ago as a way to contribute to Bhutanese civic engagement and discussion, particularly as the country transitioned from a monarchy to a democracy.

The Journal’s passionate staff have worked hard to build a community of independent thinkers on national policies, which is a relatively new concept in Bhutan. In our conversations with staff from Druk Journal, we connected over many shared social, economic, environmental and political issues. In both countries, people are increasingly concerned about climate change, biodiversity loss, the economy (including costs of living), employment, wellbeing (particularly youth mental wellbeing), globalisation, education, technology and public engagement.

One difference is that Bhutanese have a strong faith in the monarchy and loyalty to the King, with some fearing the relatively new system of democracy may break the peace of the past. Education through tools like the Journal are therefore critical for getting Bhutanese people engaged in civic thinking and public policy. We found it very useful to read Journal articles to get an insight into how Bhutan is transitioning from a traditional community into a modern one without losing their culture. Learn more about the Journal and read prior editions.[70]

Working together for the future

As guests in the country, we felt the strong pride Bhutanese have in their cultural heritage and their hope as they prepare for a future full of complex challenges. Perhaps this is another reason why the country has chosen the tagline ‘Believe’. You can feel the strong faith the Bhutanese have in the leadership of their King, their Buddhist faith and the country’s vision for the future. Bhutan is determined to prove to the world that there is a different, gentler way of doing things that focuses on the long term. It is a powerful message, and we cannot help but hope some of Bhutan’s policy ideas spread across the world.

It is clear Bhutan is very different to New Zealand in many respects; however, we found many things the countries could learn from one another. Our meetings were a timely reminder that even though people may appear different, we share the same hopes for the future, and we will need to work together to achieve these. As Bhutan’s former Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay said in his famous 2016 TED talk, the world needs Bhutan and Bhutan needs the world: ‘I invite you to help me, to carry this dream beyond our borders to all those who care about our planet’s future. After all, we’re here to dream together, to work together, to fight climate change together, to protect our planet together. Because the reality is we are in it together.’ [71]

We are very grateful to the people who took time to meet with us and answer our (sometimes very extensive!) questions. Please refer to the complete list of names and organisations in Table 1. We organised our trip through Kinley Gyeltshen; we felt in very safe hands and had fun with his brother (and driver), Aku.

You can follow the Institute’s research on ecological corridors on our website under EcologicalCorridorsNZ. Please do not hesitate to get in touch if you have any further questions or ideas.

Learning about Bhutan’s conservation policies at the Forest Monitoring and Information Division, Department of Forests and Park Services with (left to right) Dorji Wangdi, Arun Rai, Wendy and Kinley Tshering.

Josie, Annie and Wendy meeting with Dr. Pema Wangda from Bhutan for Life.

Wendy meeting with Jamyang Tenzin. The window behind looks out over the gardens and courtyard below. This is where the King comes to greet the new government after the elections.

Table 1: McGuinness Institute Meetings in Bhutan (April 2023)

| Meeting Date | Location | Organisation | Contact Name |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Department of Tourism | Ms Carissa Nimah Chief Marketing Officer |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Druk Journal Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy |

Dasho Kinley Dorji Editor |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Druk Journal Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy |

Siok Sian Pek-Dorji Founding Executive Director |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Druk Journal Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy |

Ms Ugyen Lhamo Programme Officer |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Royal Society for Protection of Nature (RSPN) | Dr Kinley Tenzin, PhD Executive Director |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Centre for Bhutan & GNH Studies (CBS) | Karma Wangdi Chief Research Officer |

| Mon 17 April | Thimphu | Bhutan for Life Fund Secretariat | Dr Pema Wangda, PHD Executive Director |

| Wed 19 April | Bumthang | UWICER (Ugyen Wanchuck Institute for Conservation and Environmental Research) | Dr Sangay Tiger, PhD Head, Education & Capacity Building Services |

| Wed 19 April | Bumthang | Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry | Pankey Dukpa Chief Forestry Officer |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Dept of Forest and Park Services, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources | Sonam Wangdi Chief, Nature Conservation Division |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Dept of Forest and Park Services, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources | Namgay Bidha Nature Conservation Division |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Dept of Forest and Park Services, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources | Norbu Yangdon Nature Conservation Division |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Dept of Forest and Park Services, Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources | Tshering Pem Nature Conservation Division |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | GovTech Agency Bhutan | Jigme Tenzing Acting Secretary |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Forest Monitoring and Information Division, Department of Forests and Park Services | Dorji Wangdi Principal Forestry Officer |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Forest Monitoring and Information Division, Department of Forests and Park Services |

Arun Rai |

| Tue 25 April | Thimphu | Forest Monitoring and Information Division, Department of Forests and Park Services | Kinley Tshering Chief Forestry Officer |

| Wed 26 April | Thimphu | Office of the Prime Minister & Cabinet Royal Government of Bhutan |

Jamyang Tenzin Deputy Chief Attorney |

| Wed 26 April | Thimphu | Office of the Prime Minister & Cabinet Royal Government of Bhutan |

Chencho Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister |

Endnotes

[1] Norbu, D. and Karan, P. (28 April 2023). Bhutan. Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2023 from www.britannica.com/place/Bhutan

[2] My Life Elsewhere. (n.d.). Country Size Comparison: Bhutan compared to New Zealand. Retrieved 30 June 2023 from www.mylifeelsewhere.com/country-size-comparison/bhutan/new-zealand

[3] Youn, S. (18 October 2017). Visit the World’s Only Carbon-Negative Country. National Geographic. Retrieved 9 June 2023 from www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/carbon-negative-country-sustainability

[4] Norbu, D & Karan, P. (28 April 2023). Bhutan. Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2023 from www.britannica.com/place/Bhutan

[5] BBC. (21 March 2023). Bhutan Country Profile. Retrieved 9 June 2023 from www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12480707

[6] World Bank Data. (n.d.). Bhutan. Retrieved 21 June 2023 from data.worldbank.org/country/bhutan

[7] World Bank Data. (n.d.). New Zealand. Retrieved 21 June 2023 from data.worldbank.org/country/new-zealand

[8] Norbu, D & Karan, P. (28 April 2023). Bhutan. Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2023 from www.britannica.com/place/Bhutan

[9] Oliver, W., Blyth, C., Moran, W., Raewyn, D., Vowles, J. & Sinclair, K. New Zealand. Britannica.Retrieved 2 August 2023 from www.britannica.com/place/New-Zealand

[10] Tzung, S. (12 September 2022). Carbon Negativity In Bhutan: An Inverse Free Rider Problem. Harvard International Review. Retrieved 9 June 2023 from hir.harvard.edu/carbon-negativity-in-bhutan-an-inverse-free-rider-problem

[11] WWF. (n.d.). Biological Corridors. Retrieved 9 June 2023 from www.wwfbhutan.org.bt/projects_/bhutan_biological_conservation_complex/biological_corridors

[12] Bhutan Department of Tourism. (13 December 2023). Green Bhutan: Sustainability projects. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from bhutan.travel/journal/news/green-bhutan-an-overview-of-the-sustainability-projects-ongoing-in-bhutan

[13] Stats NZ. (27 October 2022). New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions. Retrieved 15 June 2023 from www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/new-zealands-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[14] Convention on Biological Diversity. (n.d.). Country Profiles: Bhutan – Main Details. Retrieved 27 June 2023 from www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=bt

[15] Rondeau, E. (1 August 2017). Wild tigers of Bhutan – in pictures. Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2017/aug/01/wild-tigers-of-bhutan-in-pictures

[16] Department of Conservation. (n.d.). Help us reclassify stewardship land on the West Coast. Retrieved 21 June 2023 from www.doc.govt.nz/get-involved/have-your-say/all-consultations/2022-consultations/help-us-reclassify-stewardship-land-on-the-west-coast

[17] Royal Government of Bhutan (2008). Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008.

[18] Goering, L. (4 November 2021). Forget net-zero: meet the small-nation, carbon-negative club. Reuters. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.reuters.com/business/cop/forget-net-zero-meet-small-nation-carbon-negative-club-2021-11-03

[19] Wismayer, H. (8 December 2023). See the relentless beauty of Bhutan – a kingdom that takes happiness seriously. National Geographic. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/trans-bhutan-trail

[20] UN Environment Programme. (9 November 2021). State of the climate. Retrieved 16 June 2023 from www.unep.org/explore-topics/climate-action/what-we-do/climate-action-note/state-of-climate.html

[21] Our World in Data, based on Jones, M. W., Peters, G. P., Gasser, T., Andrew, R. M., Schwingshackl, C., Gütschow, J., Houghton, R. A., Friedlingstein, P., Pongratz, J., & Le Quéré, C. (2023). National contributions to climate change due to historical emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide [Data set]. Retrieved 15 June 2025 from ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions

[22] Stats NZ. (27 October 2022). New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions. Retrieved 15 June 2023 from www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/new-zealands-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[23] Ministry for the Environment. (December 2008). Marine Areas with Legal Protection. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from environment.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Files/Environmental-Report-Card-Marine-Areas-with-Legal-protection_0.pdf

[24] Joy, Dr. M. & McLean, S. (2 May 2019). NZ has the world’s highest proportion of species at risk. Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka. Retrieved 21 June 2023 from www.wgtn.ac.nz/news/2019/05/nz-has-worlds-highest-proportion-of-species-at-risk

[25] Williams, Hon P. (20 December 2022). New Zealand welcomes new global deal for nature [media release]. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.beehive.govt.nz/release/new-zealand-welcomes-new-global-deal-nature

[26] Vance, A. (29 October 2022). A decade of wrangling, but dolphins and seabirds off the South Island’s east coast remains unprotected. Stuff. Retrieved 14 June 2023 from www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/130147040/a-decade-of-wrangling-but-dolphins-and-seabirds-off-the-south-islands-east-coast-remain-unprotected

[27] Bhutan Department of Tourism. (May 2023). An anatomy of the new national brand – Bhutan believe. Retrieved 13 June 2023 from bhutan.travel/journal/editorial/an-anatomy-of-the-brand-bhutan-believe

[28] Yenginsu, C. (5 July 2023). Famous for Happiness, and Limits on Tourism, Bhutan Will Triple Fees to Visit. New York Times. Retrieved 16 June 2023 from www.nytimes.com/2022/07/05/travel/bhutan-tourism.html

[29] Reuter. (19 June 2023). Bhutan reducing its daily tourist tax for visitors who stay longer. CNN. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from edition.cnn.com/travel/bhutan-reducing-daily-tourist-tax-intl-hnk/index.html

[30] Ping, C. (20 July 2022). Bhutan revises its tourism policy to redefine High Value Low Volume tourism. Daily Bhutan. Retrieved 16 June 2023 from www.dailybhutan.com/article/bhutan-revises-its-tourism-policy-to-redefine-high-value-low-volume-tourism

[31] Bhutan Department of Tourism. (January 2023). Bhutan’s Sustainable Development. Retrieved 9 June 2023 from bhutan.travel/journal/editorial/bhutan-s-sustainable-development-fee

[32] Bhutan Department of Tourism. (January 2023). Bhutan’s Sustainable Development Fee. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from bhutan.travel/journal/editorial/bhutan-s-sustainable-development-fee

[33] Cadogan, T. (23 March 2023). Why Bhutan – home to one of the world’s most intriguing royal families – is the last Shangri-La. Tatler. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.tatler.com/article/why-bhutan-is-the-last-shangri-la

[34] Tobgay, T. (2016). This country isn’t just carbon neutral – it’s carbon negative. TED. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.ted.com/talks/tshering_tobgay_this_country_isn_t_just_carbon_neutral_it_s_carbon_negative?language=en

[35] HEROES, UWICER. (n.d.). Himalayan Environmental Rhythms Observation and Evaluation System. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from heroes.uwicer.gov.bt/home

[36] Rinzin, C. (January 2006). On the Middle Path: The Social Basis for Development in Bhutan. Nederlandse Geografische Studies. Retrieved 16 June 2023 from www.researchgate.net/publication/46678556_On_the_Middle_Path_The_Social_Basis_for_Sustainable_Development_in_Bhutan

[37] Royal Government of Bhutan. (2008). Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008.

[38] Zangpo, T. (23 May 2023). GNH Survey: Citizen’s well-being and happiness touch 93.6 percent. Kuensel. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from kuenselonline.com/gnh-survey-citizens-well-being-and-happiness-touch-93-6-percent

[39] Zangpo, T. (23 May 2023). GNH Survey: Citizen’s well-being and happiness touch 93.6 percent. Kuensel. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from kuenselonline.com/gnh-survey-citizens-well-being-and-happiness-touch-93-6-percent

[40] Rinzin, C. (January 2006). On the Middle Path: The Social Basis for Development in Bhutan. Nederlandse Geografische Studies. Retrieved 16 June 2023 from www.researchgate.net/publication/46678556_On_the_Middle_Path_The_Social_Basis_for_Sustainable_Development_in_Bhutan

[41] Beaglehole, R. & Bonita, R. (7 March 2015). Development with values: lessons from Bhutan. Lancet. Retrieved 28 June 2023 from www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60475-5/fulltext

[42] Rinzin, Y. C. & Thoman, M. (20 March 2023). Your Questions Answered: What is Bhutan’s Gross National happiness Index? Asian Development Blog. Retrieved 15 June 2023 from blogs.adb.org/blog/your-questions-answered-what-bhutan-s-gross-national-happiness-index

[43] New Zealand Treasury. (30 March 2023). Measuring wellbeing: the LSF Dashboard. Retrieved 15 June 2023 from www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/measuring-wellbeing-lsf-dashboard

[44] National Assembly of Bhutan. (2014). About NAB: Overview. Retrieved 19 June 2023 from www.nab.gov.bt/en/about/overview-national-assembly

[45] National Assembly of Bhutan. (2014). About NAB: Overview. Retrieved 19 June 2023 from www.nab.gov.bt/en/about/overview-national-assembly

[46] Royal Government of Bhutan. (2008). Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008.

[47] Chen, A. (19 January 2021). What are the different local governments in Bhutan? Daily Bhutan. Retrieved 15 June 2023 from www.dailybhutan.com/article/what-are-the-different-local-governments-in-bhutan

[48] Royal Civil Service Comission, Royal Government of Bhutan. (n.d.). Eligibility Criteria. Retrieved 15 June 2023 from /www.rcsc.gov.bt/en/eligibility-criteria

[49] Mancg, T & Whyte, A. (21 June 2023). Michael Wood resigns as minister after further shareholdings revealed. Stuff. Retrieved 30 June 2023 from www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/132380317/michael-wood-resigns-as-minister-after-further-shareholdings-revealed

[50] Witton, B. (16 June 2023). Race Relations Commissioner Meng Foon resigns over failure to declare $2m conflict of interest. Stuff. Retrieved 30 June 2023 from www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/132347827/race-relations-commissioner-meng-foon-resigns-over-failure-to-declare-2m-conflict-of-interest

[51] WION Web Team. (12 February 2023). Bhutan Crown Prince Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck, 7, is country’s first digital citizen. Retrieved 20 July 2023 from www.wionews.com/world/bhutan-prince-jigme-namgyel-wangchuck-7-is-countrys-first-digital-citizen-565070

[52] Dig Watch. (12 June 2023). Bhutan to pass National Digital Identity Bill after being introduced to National Assembly. Retrieved 19 July 2023 from dig.watch/updates/bhutan-to-pass-national-digital-identity-bill-after-being-introduced-to-national-assembly

[53] Cavanaugh, L. (17 July 2023). A Conversation with Jigme Tenzing, Acting Secretary of GovTech Bhutan. Retrieved 20 July 2023 from interweavegov.substack.com/p/a-conversation-with-jigme-tenzing

[54] Borak, M. (10 July 2023). Bhutan adopts National Identity Bill. Retrieved 19 July 2023 from www.biometricupdate.com/202307/bhutan-adopts-national-identity-bill

[55] Borak, M. (10 July 2023). Bhutan adopts National Identity Bill. Retrieved 19 July 2023 from www.biometricupdate.com/202307/bhutan-adopts-national-identity-bill

[56] The Bhutan Live. (21 June 2023). National Digital Identity Bill: Paving the Way for Inclusion and Equity in the Digital Era. Retrieved 21 June 2023 from thebhutanlive.com/nation/national-digital-identity-bill-paving-the-way-for-inclusion-and-equity-in-the-digital-era

[57]Andersen, Hon G. (30 March 2023). Govt helps to protect New Zealanders digital identities. Retrieved 19 July 2023 from www.beehive.govt.nz/release/govt-helps-protect-new-zealanders-digital-identities-0

[58] Tashi, N. (25 November 2020). Nation’s waste on the scale: The first Bhutan waste inventory report. IOS Press. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from content.iospress.com/articles/statistical-journal-of-the-iaos/sji200742

[59] Bhutan Believe. (13 December 2023). Green Bhutan: Sustainability projects. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from bhutan.travel/journal/news/green-bhutan-an-overview-of-the-sustainability-projects-ongoing-in-bhutan

[60] Royal Government of Bhutan (2008). Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008.

[61] Gross National Happiness Commission, Royal Government of Bhutan (2018). Twelfth Five Year Plan 2018-2023 Volume II: Central Plans. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/bhutan_12fyp-volume-ii-central-plans.pdf

[62] Radio New Zealand. (29 March 2023). New nationwide recycling and food scraps strategy unveiled. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/486958/new-nationwide-recycling-and-food-scraps-strategy-unveiled

[63] Radio New Zealand. (29 March 2023). New nationwide recycling and food scraps strategy unveiled. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/486958/new-nationwide-recycling-and-food-scraps-strategy-unveiled

[64] Radio New Zealand. (29 March 2023). New nationwide recycling and food scraps strategy unveiled. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/486958/new-nationwide-recycling-and-food-scraps-strategy-unveiled

[65] Carmen Busquets. (2020). Bhutan for Life. Retrieved 23 June 2023 from www.carmenbusquets.com/bhutan-for-life

[66] Bhutan Believe. (13 December 2023). Green Bhutan: Sustainability projects. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from bhutan.travel/journal/news/green-bhutan-an-overview-of-the-sustainability-projects-ongoing-in-bhutan

[67] Ardern, Hon J & Shaw, Hon J. (31 October 2021). Govt increases contribution to global climate target [media release]. Retrieved 26 June 2023 from www.beehive.govt.nz/release/govt-increases-contribution-global-climate-target

[68] BBC (21 March 2023). Bhutan Country Profile. Retrieved 9 June 2023 from www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12480707

[69] Royal Bhutanese Embassy, New Delhi, India. (n.d.). Bhutan-India Hydropower Relations. Retrieved 28 June 2023 from www.mfa.gov.bt/rbedelhi/bhutan-india-relations/bhutan-india-hydropower-relations

[70] Druk Journal. (2023). About. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from drukjournal.bt/about

[71] Tobgay, T. (2016). This country isn’t just carbon neutral – it’s carbon negative. TED. Retrieved 12 June 2023 from www.ted.com/talks/tshering_tobgay_this_country_isn_t_just_carbon_neutral_it_s_carbon_negative?language=en