The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the largest collective public health response in the history of Aotearoa New Zealand. This book provides a valuable record of this period which will help us better prepare for and ideally prevent future threats of this scale.

– Professor Michael Baker, epidemiologist, University of Otago Wellington

Each year, the McGuinness Institute team gets together to plan our annual work programme. We select projects based on where we see gaps in New Zealand’s research and public policy, which often means we focus on long-term policy impacts that go beyond the short-term three-year election cycle. We choose projects where we think we can benefit New Zealand’s future through our independent, non-partisan approach.

One such project which has taken up a significant amount of time this year has been producing an updated version of our book, COVID-19 Nation Dates: A New Zealand timeline of significant events during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Nation Dates series of books aims to provide the public with a record of our past in an easy-to-access and well-referenced format.

The Institute’s research on COVID-19 in New Zealand has been ongoing since the start of the pandemic, with our small team busy collating media articles, investigating press releases, undertaking interviews, contacting academics and epidemiologists, meeting with public servants and submitting OIA requests to different government organisations. Our second edition of COVID-19 Nation Dates is a substantial piece of work, with the second edition taking over six months of work from our team of researchers, designers and editors. This effort is shown by the size of the final product: 537 pages and more than 1,400 references.

We are immensely grateful to all the experts and editors who have helped make our work concise and accurate. The second edition is now available for order in our online shop.

My favourite quote that continues to resonate is from the UK COVID-19 Inquiry – Module 1:

Flaw 5: Capabilities and capacity

3.66. It is critical that the assessment of risk is connected to practical capabilities and capacity – namely, what can actually be done in response to an emergency. In this way, risk assessment should be connected to strategy and planning, which have to take account of the reality in terms of preparedness and resilience on the ground.

If risk assessment does not take into account what is and is not practically feasible, it is an academic exercise distant from those on whom it will ultimately have an impact. This is what happened in the UK.

That all sounds like a lot of effort on a topic we would rather forget … why did we publish this book?

Looking back over time, pandemics can be seen as part of the normal cycle of events: what I call ‘The Long Normal’… Pandemics are frequent enough to cause major damage, but irregular enough for knowledge not to be passed on from one generation to another. This, when compounded with our desire to forget about the unpleasant, what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls a cycle of ‘panic–then–forget’, means we need to double down in the short term to identify lessons for the long term (WHO, 2020a).

Extract from COVID-19 Nation Dates

COVID-19 Nation Dates was written to provide insights by recording the impact of COVID-19 in New Zealand between January 2020 to mid- to late 2024. This was a unique, intense time for our country, with many significant public policy decisions made under pressure. As public policy enthusiasts, we observed the speed at which decisions were made, often relying on incomplete information, and wondered who was tracking their implications. As the pandemic progressed, we were disappointed that despite their huge impacts on public life, policy decisions were not being recorded or shared. In response to this policy gap, we decided to write COVID-19 Nation Dates to provide ‘a warts and all’ detailed history to help look forward to the future.

What is the book about?

The answer to this can best be summed up by an extract from early in the book:

COVID-19 Nation Dates is a record of Aotearoa New Zealand’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is designed to chronicle our recent history through the lenses of science, statistics, management and communications. This is the second edition of this book. Timelines are used by futurists to understand both the context of a specific event and the narrative or pattern suggested by a group of events. The 706 events listed in Chapter 7 illustrate the scale and pace of change. The aim is to provide a useful tool for shaping our collective future. This book aims to be a comprehensive and objective list of all major COVID-19-related events over time. At best, I hope our contribution is seen as a solid attempt at providing a public record, which others will follow and improve upon.

Extract from COVID-19 Nation Dates

Five observations

Our second edition of COVID-19 Nation Dates contains 706 entries, building on the first edition’s 430 entries. The Institute, alongside our collaborators, have worked hard to represent the breadth of events that occurred over this time. As we undertook this research, we started to identify key trends, threads and lessons that stood out. A non-partisan approach is essential for this kind of analysis, investigating what happened, how New Zealand responded and how outcomes could be improved. By taking a step back and observing New Zealand’s COVID-19 response as a whole, we came away with a number of important reflections for the next pandemic.

Below we share five key lessons which we hope will help make the next pandemic response faster, safer and cheaper for all New Zealanders:

1. Pandemics require a coordinated, all-of-government response; the response should not be led by Ministry of Health (or any individual ministry)

A whole-system civil emergency requires a whole-system government response. For example, in World War I, the political parties formed a coalition Government (McAloon, J., 2014). Arguably, not enough was done to create unity in Parliament early on in the pandemic … In our view, this failure to create a united and informed Parliament early in the process contributed to the division that occurred later. In the future, New Zealanders should expect political parties to form a coalition when the challenge we face calls for a united front. We may need to engage all eyes, ears and brains when dealing with the next pandemic.

Extract from COVID-19 Nation Dates

In times of crisis, an ongoing authority will help keep the messaging consistent and our politicians accountable. A coordinated, ongoing authority would mean we respond better to natural disasters, wars and civil unrest, and to medical emergencies such as pandemics.

The public communications undertaken by the Labour Government during the early stages of COVID-19 (such as the iconic 1pm daily briefings) resulted in worldwide acclaim and celebrity status for Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and Director-General of Health Sir Ashley Bloomfield KNZM. These clear, regular daily briefings were an effective piece of public communications management, giving the impression that everything was under control and New Zealanders just had to follow each set of guidelines to ‘save lives’. Behind this calm front however, our research identified a fractured political system. Inconsistencies and issues were caused by different ministries and departments not communicating with one another.

Giving a single agency responsibility for managing the pandemic would have resulted in a more coordinated approach, allowing policy to be enacted faster in order to respond more quickly to the issues at hand. Government, businesses and the community all need to be on the same page so when a crisis hits we do not waste time deliberating, but instead can spring straight into action to save lives as quickly as possible.

2. Build an agile plan and stress-test it regularly

Looked at in the context of history, pandemics are inevitable. They have occurred in the past and will continue to occur in the future. The Government needs to have a strong pandemic response plan. This plan should be developed with the public, especially medical professionals and business leaders, and we all need to stress-test this plan regularly. When the pandemic arrived in 2020, our Government was inadequately prepared. This resulted in a number of decisions made on the fly and under immense stress.

An example of the pains caused by poor planning is the ad-hoc approach the Government took to border closure. Closing the border is an obvious response to an international disease; however, the Government responded with a highly criticised MIQ system that many considered was unethical, confusing and inefficient. The consequences of poor planning were significant: a number of people were stuck outside the country, leading to human rights issues. New Zealanders were unable to return home to their families, including heart-wrenching stories of pregnant or sick people stuck overseas, or people unable to return home to support their families or attend a funeral of a loved one. New Zealanders will always be spread all over the world, and plans need to be made so these people can always return safely.

The response to COVID-19 was largely designed on the fly, which meant politicians did not have time to explore the implications of their policy decisions and actions. We need to plan and prepare for all kinds of pandemics, and regularly stress-test these plans with scientists, medical professionals and business leaders. For instance, what if a pandemic occurs while there is also a cyber-attack on Government software? Or if a natural disaster means medical supplies cannot be sent to New Zealand? Our technology, climate and society are constantly changing and it is critical to design agile plans.

The Government in practice adopted three different strategies. In our view, each of those three requires deeper analysis in order to understand the costs, risks and benefits. This work should be done before the next pandemic.

3. Consider indirect and long-term impacts of policy on mental and physical health

Government’s response to COVID-19 was focused on the short term: stopping the virus spreading at all costs. It is essential to design public policy to protect human life; however, by focusing solely on mitigating the spread of COVID-19, other physical and mental health issues were not considered in policy decisions.

Strong public policy needs to consider indirect as well as direct impacts, looking at the long term as well as the short term. For instance, lockdowns had a number of negative impacts on vulnerable groups. Physical and mental health are interlinked, and the mental impacts of lockdowns are still unknown, especially for young children who missed development or elderly who suffered extreme loneliness. Some people felt forced to stay in uncomfortable, and potentially abusive, households. Children who relied on school for support and food lost their lifeline when schools were closed. There are also a significant number of heart-breaking anecdotes about people who slipped through a stressed medical system, including people unable to get doctor appointments or receive surgery, resulting in missed opportunities to diagnose and treat serious illnesses.

As well as immediate health issues caused by the disease in question, public policy responses to a pandemic need to consider the health and wellbeing of society as a whole. The costs and benefits of extreme policy measures (such as lockdowns and closing schools) should have been weighed and shared with the public. For instance, in a lockdown situation, additional support should have been provided to single parents, or carers for people with mental or physical issues. During and after the pandemic, medical professionals suffering from burnout should have received additional financial and mental support. It is essential to build a deeper understanding of how to respond to the mental and physical health impacts of a pandemic.

4. Accountability for significant financial decisions

When responding to a crisis, New Zealand needs policy mechanisms that allow action to happen fast, including for the Government to allocate funding where it is required to save lives. This rapid response model requires a high level of public trust; however, with the COVID-19 response this public accountability eroded over time.

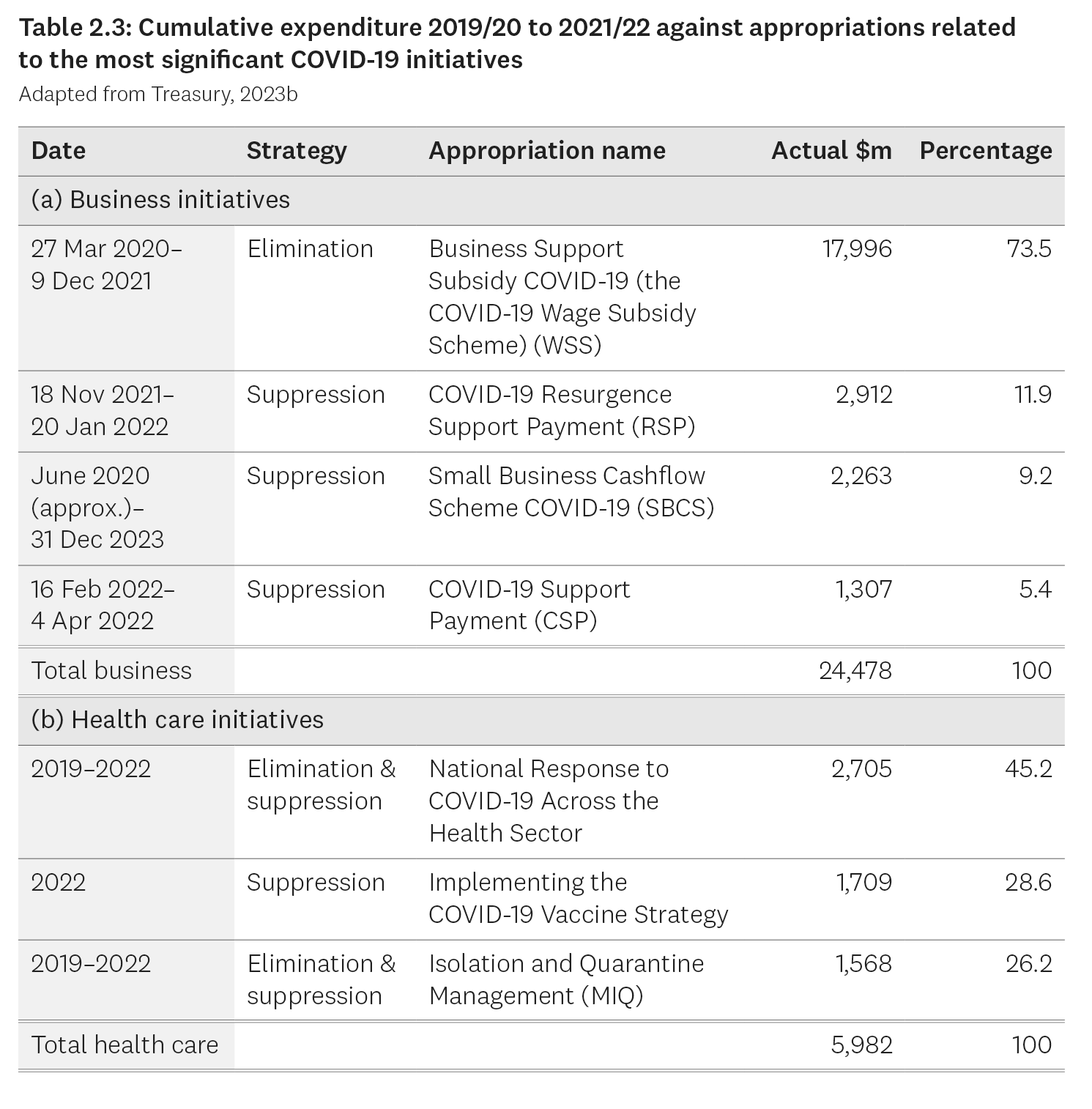

One obvious example was the COVID-19 wage subsidy. The Government spent almost $18 million on the wage subsidy scheme, a controversial scheme that allowed a significant number of people to access ‘free money’ with little accountability. It is critical to provide support to people in need; however, for such a significant use of public funds, there was not adequate accountability to ensure participants qualified and used the money as it was intended. A number of people who genuinely needed financial assistance could not access the subsidy, and in contrast, some corporates obtained subsidies that arguably they did not need over the medium term.

The amount of money the government spent was unprecedented: Table 2.3 (an extract from the book below) illustrates the Government’s expenditure related to COVID-19.

5. Employ an historian as soon as the pandemic is announced

A struggle in collating this book was knowing what actually happened: dates, names and key details were often conflicting, or missing, resulting in the Institute submitting a significant number of Official Information Act requests.

It is essential to keep a record of events as they occur, and both the Government and the media play an essential role in this process. Politicians need to share information with the public and be open to questioning by the media. The role of journalists framing questions and seeking answers cannot be underestimated. The more we attempted to find non-partisan records of history during the pandemic, the more we realised there was a lack of accessible, unbiased information on what happened in New Zealand. COVID-19 Nation Dates is an attempt to get down on paper a well-referenced, accessible record of what happened over this time.

One attempt to prepare New Zealand for future pandemics and provide recommendations based on the lessons from our COVID-19 experience is the COVID-19 Royal Commission, which was established in 2022. Inquiries play an essential role in public accountability and there is potential for this investigation to improve New Zealand’s response to the next emergency. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 Inquiry has received criticism for having narrow terms of reference under the Labour Government, and for being inconsistent, as it has changed under the National-led Government. It is now a two-part process, and we look forward to seeing its outcomes. We would suggest that the terms of reference should be wider (to be more consistent with the UK), and that it should be consistent across political changes.

Inquiries … should not be swayed by politics or partisanship. Perhaps one of the more important lessons, in retrospect, is that the epidemic select committee should not have been disestablished by the Labour Government. Instead, the committee (with its institutional knowledge of a pandemic) could have helped the country by developing a shared terms of reference for New Zealand’s COVID-19 Inquiry, reviewing the OAG’s 2022 recommendations, overseeing the update of the 2017 pandemic plan, and establishing smaller targeted inquiries, in order to reduce costs and implement obvious changes at pace.

There is a balance between taking too little time to inquire into an issue (and therefore not identifying the lessons) and taking too much time and doing nothing (and therefore not actioning the lessons). Two risks exist: the risk of another pandemic occurring before the report’s recommendations are published and implemented, and/or the risk of a long gap meaning the government loses its institutional memory and sense of urgency, and as such, fails to prioritise improvements in governance before the next pandemic.

Extract from COVID-19 Nation Dates

Conclusion

These lessons are intended to act as conversation starters. As the impacts of policy decisions made in response to the pandemic shift over time, other long-term impacts may become clear and change the lessons learned. We can be certain the next crisis will be different to COVID-19; however, by using lessons from COVID-19, we can avoid making the same mistakes and do better in the future.

American investor and hedge fund manager Ray Dalio once said that decision making is a two-step process, first learning and then deciding (Dalio, 2017). What is apparent is that decision-makers had to make major decisions, often without complete or accurate information. Events simply moved too quickly for officials to prepare and provide detailed policy advice on the strategic options and policy impacts.

That is not the case today; decision-makers working on how to build a better response for the next pandemic are not limited by poor information or time constraints, but unfortunately progress remains slow. Preparing for the next pandemic requires a detailed examination of the recent pandemic.

Extract from COVID-19 Nation Dates

Our next steps

The Institute recognises that Government and officials are currently undertaking work to help New Zealand become pandemic-ready (see list on page 17 of the book), but we do not believe this task is being treated with the necessary urgency or Parliamentary oversight. This point was reemphasised by the Auditor-General in his letter to the health select committee on 1 November 2024:

Our overall assessment is that some progress has been made, but further work is required to address the recommendations from our 2020 report [Ministry of Health: Management of personal protective equipment in response to Covid-19] and to give the public assurance that New Zealand holds sufficient reserves for future emergencies.

John Ryan, Controller and Auditor-General

Given what we learned, we have put together a package of suggestions (in the form of a letter and a table) to leaders of political parties, members of the Health select committee, the Director-General of Health, the Chief Executive of the Ministry of Health | Manatū Hauora, and the Chief Executive of Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora.

Next year we hope to publish a signature report on pandemic management, under the banner of our Project 2058. It will incorporate the findings from the Royal Commission of Inquiry (phase 1) and from international reports and reviews. So, the work continues.

Thank you for your interest.

Wendy and the team at the Institute