Revisiting Tomorrow: Navigating with Foresight was a public event hosted by the McGuinness Institute at the National Library of New Zealand on 30 October 2019. The former prime minister Rt Hon Jim Bolger was joined by former members of the Commission for the Future (Dame Silvia Cartwright) and the New Zealand Planning Council (Peter Rankin) and current future thinkers (Tāmati Kruger and Professor Amy Fletcher) to explore the impacts of the two organisations. Following their discussion of the history of past future-thinking groups, the panel reflected on what can be learned from these organisations and how New Zealand now might integrate these lessons to better embed foresight into public policy in 2020 and beyond.

Setting the Context – Wendy McGuinness

Wendy opened the event by summarising the history of the Commission for the Future and the New Zealand Planning Council. She explained that these two early foresight-focused institutions were chosen as there was enormous value in examining the lessons from their tenure and use them in current foresight thinking. She shared that in 1976 the Task Force on Economic and Social Planning published the report New Zealand at the Turning Point. Based on the report’s recommendations, the Commission for the Future and the New Zealand Planning Council were established under the New Zealand Planning Act 1977.

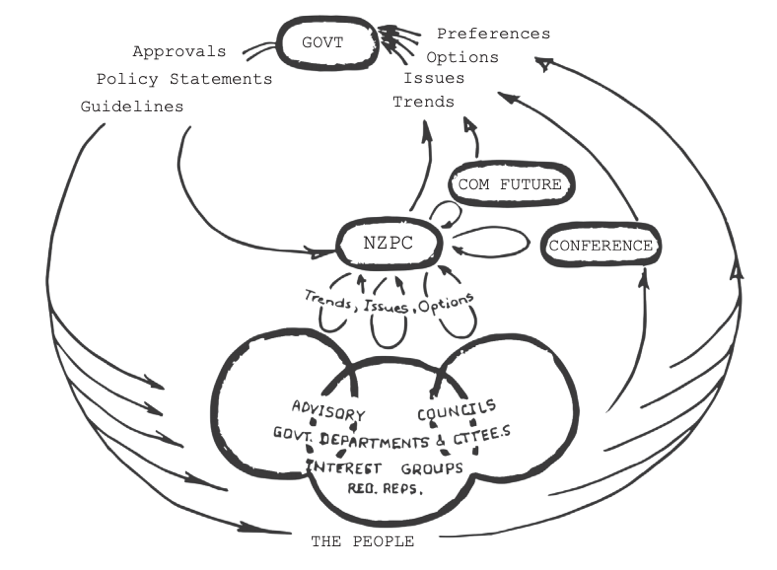

The two organisations had influential, albeit short lifespans, and published numerous reports on key issues for New Zealand’s future. They were given an ambitious mandate to explore how to embed long-term strategy and planning in New Zealand’s public policy. The diagram below, originally from New Zealand at the Turning Point (1976), indicates how the New Zealand Planning Council and Commission for the Future were envisaged to fit into New Zealand’s ‘information flows’:

The Commission for the Future was controversially disestablished in 1982 under the Robert Muldoon-led Third National Government, while the Planning Council was disbanded in 1991 under the Jim Bolger-led Fourth National Government. The legacy of both organisations was to provide a blueprint of how foresight should be (or should not be) embedded into public policy.

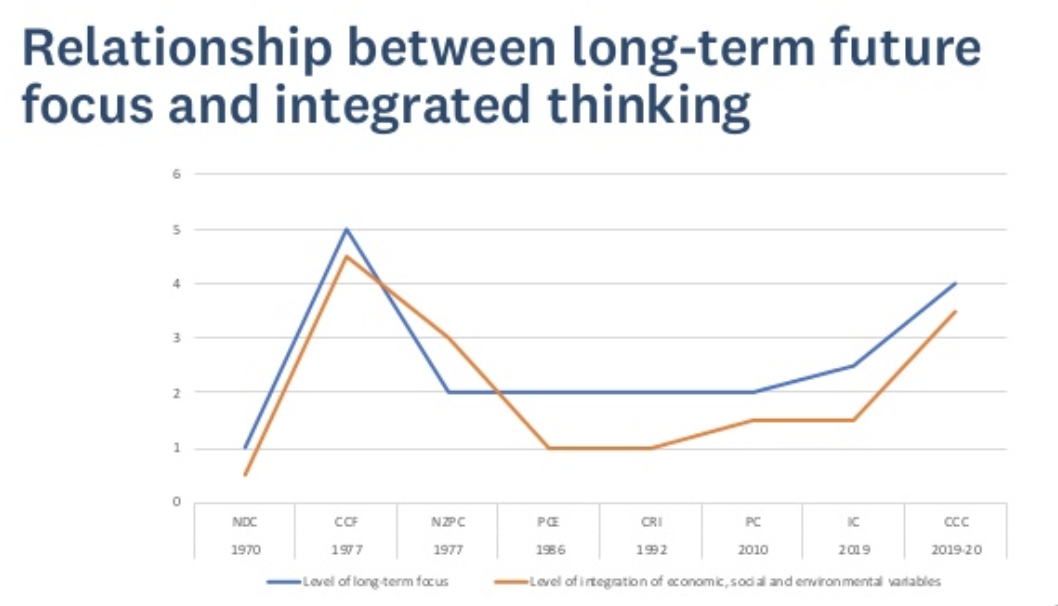

Wendy noted, that just as in 1976, New Zealand has now reached a turning point. As the world faces increasing uncertainty, particularly when navigating issues such as climate change, it is vital that New Zealand moves towards embedding foresight and long-term thinking into robust public policy. She explained that the McGuinness Institute hopes that, by looking back at the work of previous future-thinking organisations, we can provide some insight and context for emerging initiatives such as the Infrastructure Commission and the proposed Climate Change Commission. Wendy looked at the legislation that created a range of different institutions established since the Commission for the Future and found that the Climate Change Commission shared many similar characteristics to the Commission for the Future (portrayed in the following graph and explained in more detail in the SlideShare presentation below).

She also shared the words of Hon Hugh Templeton, the minister initially responsible for the Commission for the Future:

I did not put the time that I should have into trying to oversee and nurture the Planning Council and certainly the Commission for the Future. I basically blame myself for the Commission for the Future going off the rails on the security issue and inducing Muldoon to dump it (13 December 2010).

1. Rt Hon Jim Bolger, Former Prime Minister, 1990–1997

The Rt Hon Jim Bolger’s talk emphasised the need for robust, systemic government structures to deal with shocks. He began with a contextual example of the 1972 oil shocks to highlight how a system without a robust structure is incapable of solving problems. At the time of these oil shocks, New Zealand was vulnerable to rapid changes in international oil prices and as a result, suffered the economic and social consequences. New Zealand, in Bolger’s view, had failed to plan for such surges in oil prices. The oil shocks of the 1970s and a stagnating New Zealand economy proved to many in government that New Zealand needed a mechanism tasked with both planning for such scenarios, and to develop policy which greater incorporated foresight.

In his view, a current blind spot in New Zealand’s long term planning is too much of a focus on GDP in economic policy. GDP per capita is the commonly used and globally comparable measure of a country’s prosperity. However, he explained, only looking at average incomes fails to include real measures of human progress and wellbeing:

‘If we are not measuring what matters to citizens, then the measure is worse than useless because it can lead policy down a blind path… Economic growth that doesn’t consider social fairness or environmental sustainability is a recipe for disorder.’

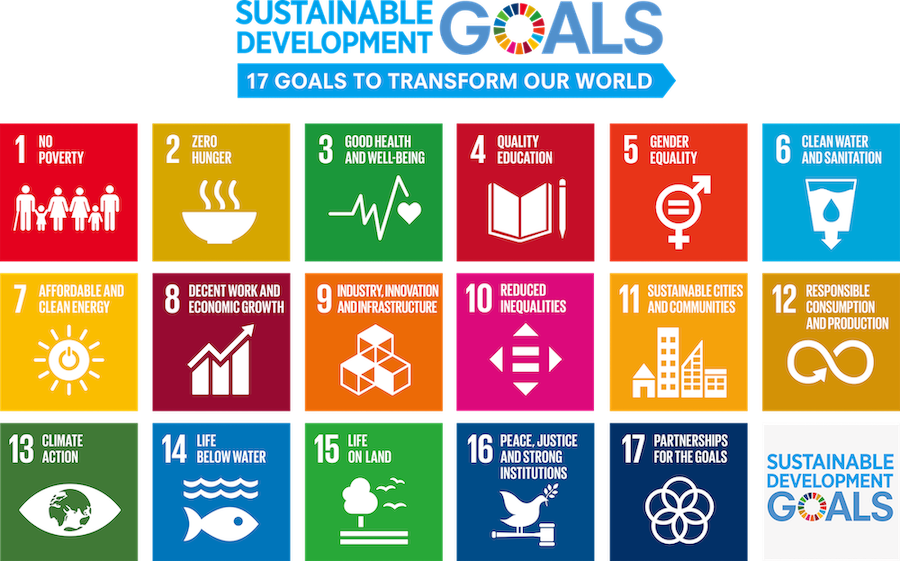

The exclusion of factors such as non-market transactions, income inequality, environmental quality, costs of negative externalities from national output, growth sustainability, perceptions of fairness/injustice, are all examples of why GDP growth should not be the sole measure of ‘success’. Bolger urged for a much more inclusive metric to measure New Zealand’s success, pointing to the already existing metric of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as one possible measure. The SDGs measure a much wider set of objectives as a new, creative and considered model of social status and progress. These are outlined in the diagram below.

Bolger closed by explaining his realisation that he doesn’t fear change. Instead, he fears old thinking and old attitudes that deny or delay the world community the opportunities that future thinking could deliver:

‘Any new attempt at planning for the future needs to focus on changing attitudes and changing thinking, changing hearts and minds, if it is to make a material difference. That’s more important than the structure.’

2. Dame Silvia Cartwright, Commissioner, Commission for the Future, 1977–1981

‘The future arrives very quickly, as I have found, and some planning and thinking about it will always pay dividends.’

Dame Cartwright shared her past experiences as a member of the Commission for the Future from its inception in 1977. Dame Cartwright highlighted that despite pushback from government the many issues the Commission studied were, in hindsight, very prescient and vital. At the time of massive oil shocks, when fuel prices became unmanageable, debates around introducing nuclear power began. She explained that when the Commission looked into this area, it learnt the New Zealand public was not comfortable with nuclear power and did not want to assume the risks associated with it. The Commission’s research was one of the first measures of New Zealand public sentiment towards nuclear weapons and power. Eventually, as is well-documented, there was a major shift towards the anti-nuclear stance, a defining feature of New Zealand politics.

Dame Cartwright also explained how risk is a key part of prudent future planning. Using the risks that New Zealand faces from natural disasters, she highlighted the Earthquake Commission (EQC) as an example of an early governmental body which focused on foresight. Analysis of risk is more sophisticated and informed today but the Earthquake Commission’s emphasis on this issue was timely. The establishment of the EQC in 1945 (well before the establishment of both the New Zealand Planning Council and the Commission for the Future) was, in itself, an acknowledgment of future hazards and a clear demonstration of prudent future planning.

Speaking of her experience of how the Commission for the Future was viewed in the wider political sphere, and ultimately the impact those views had on the institution, Dame Cartwright said:

‘The Commission for the Future’s papers were often met with cynicism, at least by the political class, and I recall vividly contemplating the irony of the situation when the Hon Bill Birch told the members, including his parliamentary colleagues that “government could not live with a body that disagreed with it”. I was too naive politically to be able to process the fact that the very government that had established a body that was structured to provide independent thinking about possible futures for New Zealand, could not cope with the fact that it was in fact doing what it was asked.’

She concluded that the Commission for the Future had bold ambitions, and even though it was bipartisan, it was not protected from the dangers of independent thinking and eventually falling out of favour with the government.

3. Peter Rankin, Chief Executive, New Zealand Planning Council, 1982–1990

Peter Rankin was the former Chief Executive of the New Zealand Planning Council from 1982 to 1990. His opening remarks set the tone for his presentation:

‘We’re talking about foresight, is this because we think it’s fun, interesting or challenging even? No, it’s because we want action. We want action based on foresight… If we are talking foresight, come on! We are talking climate change.’

Peter explained the many different elements that must be addressed when planning for the future and adapting to change. He identified an area of futures dialogue which is commonly misunderstood: the difference between ‘urgency’ and ‘importance’. He put this into context by comparing Wellington’s ‘urgent’ demand for a second Terrace Tunnel and its ‘important’ need to decrease fossil fuel emissions. Other crucial elements he identified were information which aids awareness, pathways which determines action and trust and fairness which ensure that costs and benefits are equally shared. Peter stressed that social outcomes are based entirely on public awareness, public demand and subsequent voting behaviour. Therefore, driving foresight into the public sphere to incorporate long-term thinking into all public decision making processes becomes incredibly important

Throughout his involvement with the New Zealand Planning Council, Peter said he found that long-term issues needed to be presented in ways that remained relevant over time. This became especially important when the Commission for the Future was abolished with the New Zealand Planning Act 1982 coming into force. The Act changed the scope of the Planning Council’s work from medium to long-term and required it to report on the trends and issues facing the social, economic, cultural, and environmental development of New Zealand. The Planning Council responded to this through the establishment of many monitoring groups. These groups produced regular reports with the aim to inform, remind, and update people about the trends that they were going to be dealing with.

4. Tāmati Kruger, Chief Negotiator, Tuhoe 2013 Treaty Settlement

As Tuhoe, Tāmati shared a collective story on the indigenous voice, the meaning of time within Te Ao Māori, and the disruptive force that chaos has on tikanga, and the ways of thinking about the past, present and future:

‘According to Tuhoe tikanga, the future is that affecting force that comes from the past, it is an interconnection with the past, with the present and the future.’

While reflecting on the shared colonial experience and its resulting impact on Te Ao Māori to this day, Tāmati shared the history and feelings of Tuhoe’s damage, anger, hopelessness, hatred and subsequent suppressed passion. It is this suppressed passion, he said, that leads to chaos or ‘tense mediocrity’, which damages faith in Tuhoe tikanga and ultimately becomes the barrier of disconnection between Tuhoe’s past, present and future.

In te reo, the past is referred to as ‘mua’, which translates to ‘the front’ or ‘in front of’. As the past has been experienced, it therefore lies before us and is realised (compared with its antonym – ‘muri’, which literally means ‘afterwards’). Tāmati explained that the te reo translations of past, present and future enable Te Ao Māori to be aware of the future, not afraid of it. Tāmati shared that we must learn from i ngā wā ō mua (past times), for the past is the greatest prophet of all:

‘I’m hoping that together we will create a civilisation that is founded on peace, truth and justice. I don’t want to be mediocre, but what we allow will continue – and it will haunt us all […] Life is something that we want to live well, because the future is always on time.’

5. Amy Fletcher, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Canterbury

As an associate professor of political science at the University of Canterbury, Amy said her role affords her the ability to engage with young people around issues that involve foresight. Throughout her presentation she shared many lessons which have changed and solidified her thinking around futures thinking, both from her experience growing up in the US and her career as an academic in New Zealand.

She asked the audience about youth motivation, given the often dire dialogue that surrounds the many global issues:

‘How do we get young people to feel confident about using tools, knowledge, intelligence and the past to overcome challenges and collectively move forward?’

She shared with us a story of one of her students, who she said, found that the multitude of global issues seemed insurmountable to them. But after completing a scenario based exercise, the student realised that although there are many barriers to change, we all have agency. She stressed that it is extraordinarily important to not lose confidence when considering future planning, no matter the scale of the challenge.

She emphasised that there are many insights which can continuously be pulled out of the past, which are vital in informing public policy and future planning. An interesting takeaway from her presentation was that, in her view, society seems to moving backwards, not forwards. She validated this claim with this ‘what if’ statement below.

‘If we could time travel a diplomatic expert into the present day, one from 1913, 1953 and 1993, once he or she got used to the fact that there is a whole lot more women in the room, the technologies that we use, and the way we dress, I honestly think that the one from 1913 would solve our problems first because we seem to be moving backwards not forwards.’

6. Reflections: Maddy Foreman, Sally Hett and Samu Telefoni

To close the evening’s discussion, we heard three youth perspectives reflections on the speaker’s presentations, and their own thoughts on the place of foresight within public policy: two former Institute heads of research (Sally Hett and Maddy Foreman), and a former Institute workshop participant (Samu Telefoni, who attended KiMuaNZ).

Maddy, Sally and Samu all expressed that they thought that widespread economic and social inequality was related to the low levels of civic engagement seen in New Zealand. Maddy specifically noted that the high levels of civic disengagement stem directly from the lack of trust in our parliamentarians and institutions. In her role as an advisor on the Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry, Sally had observed vast inequities across New Zealand. To her this demonstrated the public sector’s failure to truly understand and solve problems at the level of the particular groups affected. Adding to Tāmati’s point about Tuhoe’s disinterest in the ‘blame game’, Samu explained that to be equitable we need to cease shifting blame across society and instead ‘mend what has been broken, or get out of the way and let someone else do it’.

The perspective of young New Zealanders looking to the future was valuable to compare to the panel speakers. The message in aggregate, across all speakers was that we need to strive towards achieving a citizen-centric public sector which enables an informed society across all issues, irrespective of demography.

Further outputs from the event:

YouTube: We have uploaded some of the evening’s presentations onto our YouTube channel. You can view the videos here.

YouTube: We have uploaded some of the evening’s presentations onto our YouTube channel. You can view the videos here.

Revisiting Tomorrow Newspaper 1976 –1991: Copies are available at the Institute or ordered from our online store, found here. A pdf of the newspaper can be found here.

CFF and NZPC publications: If you are interested, you can view our online collection containing some of the Commission for the Future’s and New Zealand Planning Council’s publications here. We are always aiming to expand our collection of these publications, and welcome any information regarding missing publications.

Follow-up survey: We are preparing an online survey, which contains many of the unanswered audience questions from the event. When it is finalised we hope to gather your ideas and opinions around these questions.