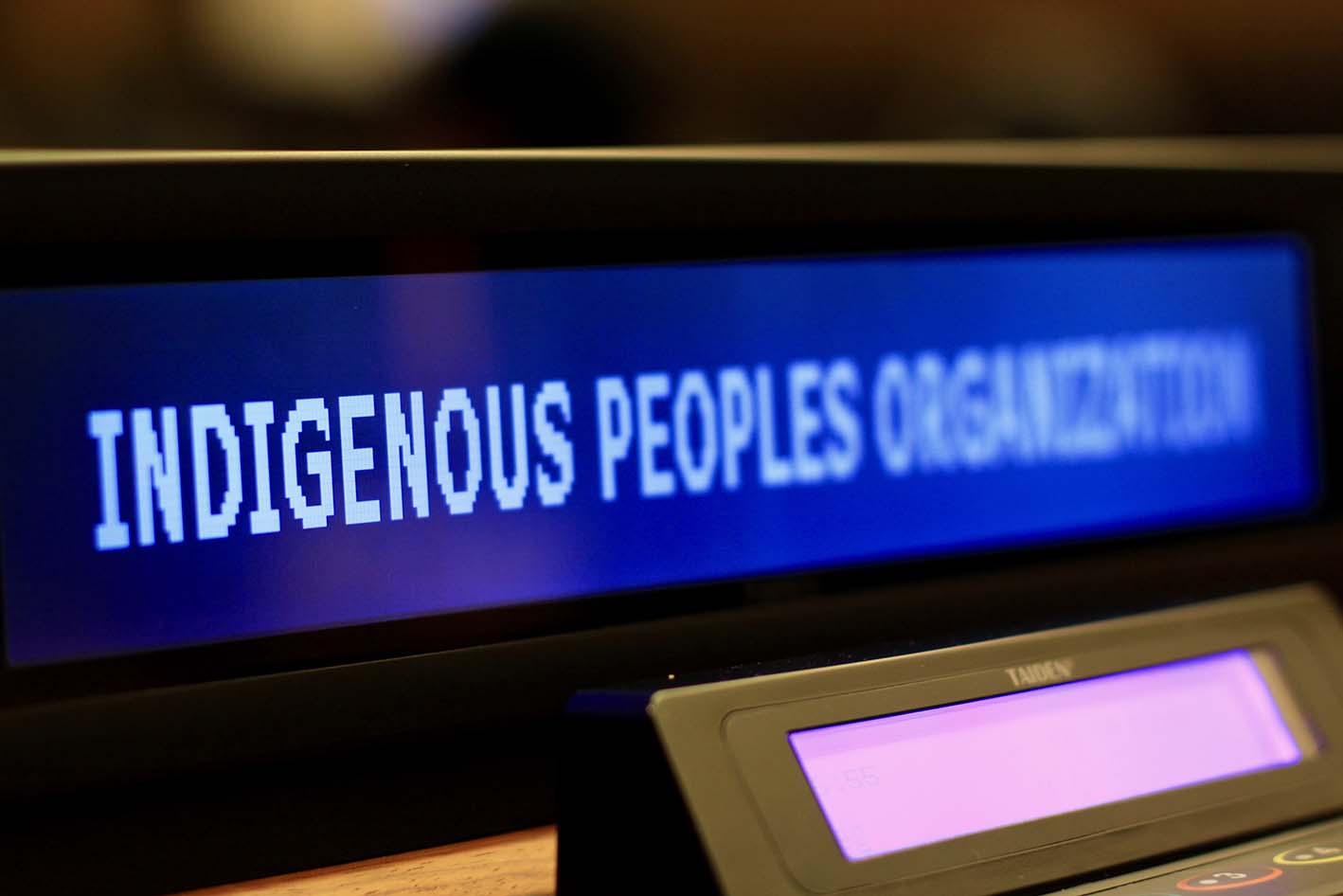

The McGuinness Institute was pleased to be able to sponsor 2017 WakaNZ workshop participant Trinity Thompson-Browne for her trip to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII). Trinity attended the seventeenth session of the forum in April 2018. The forum is intended to act as a high-level advisory body to the Economic and Social Council. The April session was themed ‘Indigenous peoples’ collective rights to lands, territories and resources’.

The Institute tries to support workshop participants to make the most of relevant opportunities arising in the year following their workshop and we have previously also supported Trinity’s media initiative for Māori youth: Fruit from the Vine. Read our blog about its launch here.

Trinity’s reflections on her UN experience are presented below, as well as appearing on Fruit from the Vine.

Nearing eight months since returning from New York, the experiences I had over there have been running through my mind a lot lately. With more of our whānau — rangatahi especially — engaging in the UN’s forums than ever before, the need for more open kōrero about this space is becoming more and more pressing. Heoi nei nā te take o te tuhinga nei; herein lies the purpose of this piece.

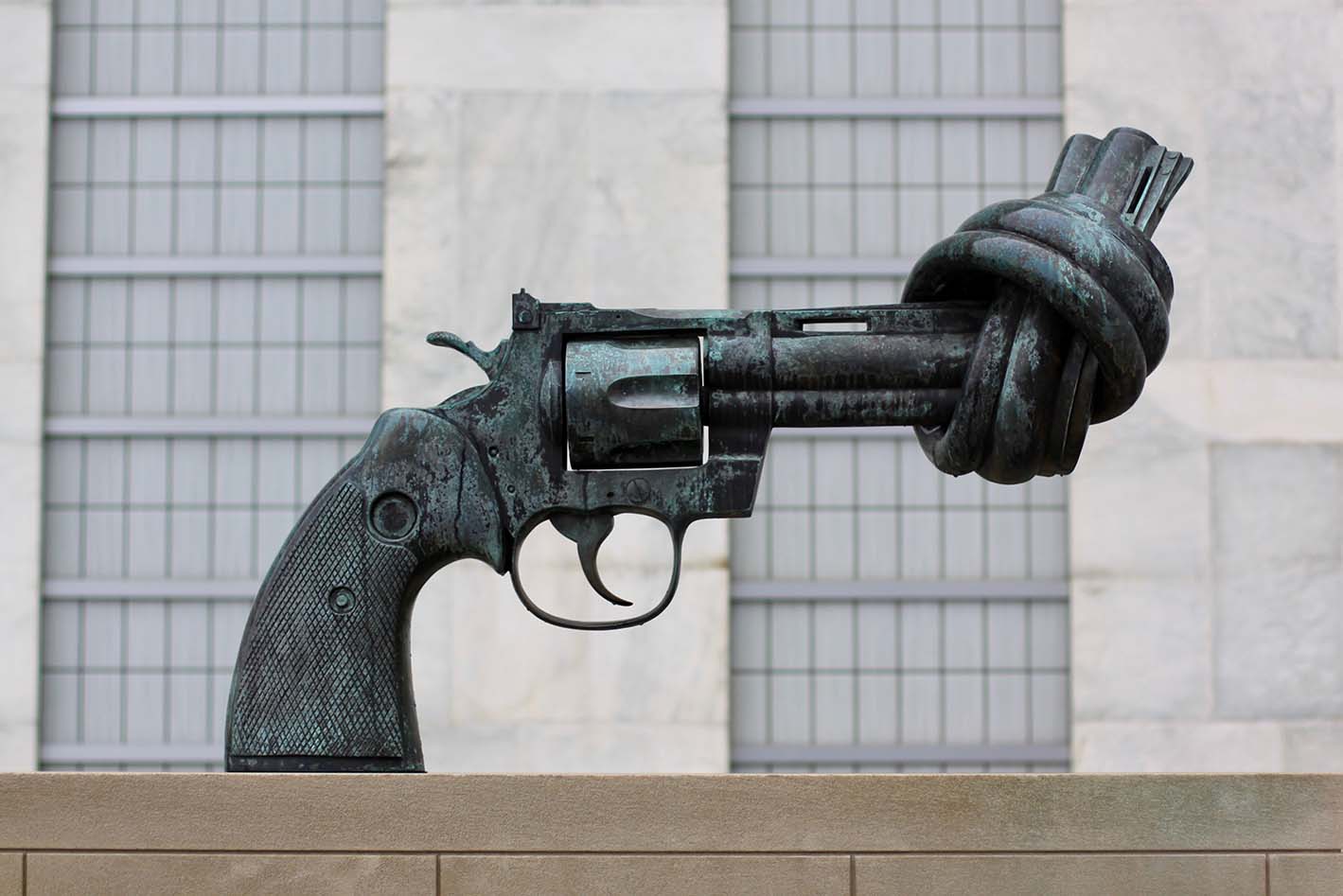

Often appearing like a fog from Hinekohurangi (goddess of the fog), the UN from the outside can seem a mix of mysterious and prestigious, endowing anyone who has entered into ‘Te Kohu’ or ‘The Fog’ (which is what I’m gonna call the UN from now on) with that same mauri. You might have mates that’ve been; maybe you’ve been yourself; maybe you’re curious about going; or maybe you’re prepping to head over soon. Wherever this kōrero finds you, may it be like Tāwhirimātea’s winds clearing out the myths making up Te Kohu. Let’s get started.

1. By being in a space, you protect yourself from the price of absence. At the same time, you expose yourself to the consequences of presence.

This was probably my biggest learning. There were voices lost before Te Kohu even came into sight, and stories of injustice that never found flight in Tāwhiri’s winds because the US denied their visas; there were people who could never go back to their whenua because they’d be incarcerated or killed if they ever returned; and others still who risked their lives to be at these hui and couldn’t be seen on film. For a lot of our indigenous whānau, whether absence or presence, the price of entering Te Kohu was already tipped between life or death.

Even without that fundamental threat though, it’s taxing. The balance is that if you’re there, you can be be an earpiece/mouthpiece for your people, which is so incredibly vital. But if you’re there, the intensity of Te Kohu can come to feel like it’s separating you from your sense of self. You’re often bearing witness to the worst of the worst that’s happening around the world, which, more often than not, is then followed by kōrero from governments announcing that they are doing a great job with their indigenous peoples. It’s infuriating. And to then be recognising less and less of yourself as the days pass, it’s like watching the whenua slowly disappearing underneath your feet with no ability to stop it.

For me, going into Te Kohu was the single most revealing experience of my life. As it turned out, my sense of self was neither strong enough nor deep enough to withstand being in a space like that and journeying into it simply served to make that fact very obvious, very quickly. Those fundamental questions of, ‘Who are you? What are your values? Who are you to be here?’ did their pūkana at minimum twice a day and it was humbling to not have a response. However hard though, the pain from Te Kohu is something I’ve come to appreciate as a gift because it taught me what being truly rooted in oneself in the face of such intensity actually looks like.

Will I do it all again? Āe. Why? The difference between choosing presence over absence is that absence affects everyone — there’s no telling the pain that’ll be caused if we don’t show up. Presence on the other hand, that mamae’s like a burn; you can see it and it only affects you/your rōpū. No matter how painful, it heals with time.

2. Be a good tīpuna; think long-term.

Before the actual week-long hui started, we had three days of prep wānanga with our indigenous whānau. As we walked in on that first day, there were folders on all of the seats and written on the front was the phrase ‘Be A Good Ancestor’. That’s where this learning comes from. During our prep time, it became increasingly apparent that the way many indigenous whānau understood Te Kohu was through this whakaaro that ‘I am not just me’, but ‘I am the culmination of every tīpuna before me and every uri after me’. And so being a good tīpuna came to mean thinking intergenerationally from the get-go about how actions now impacted on the days, weeks and years beyond, whether that was to do with our environment, our people or ourselves.

3. Keep the ara (path) clear.

As a natural progression coming from the idea of intergenerational thinking, this learning is about honouring the hard yards of everyone who’s journeyed before us into Te Kohu. Even just within our culture, the constant mahi of people like Teanau Tuiono, Tina Ngata, Valmaine Toki and Tui Shortland has created a wide ara for Māori (rangatahi or not) to come into Te Kohu. Everyone who enters by way of that ara in turn accepts the responsibility to protect it and, even if it’s not in your power to help advance it, maintenance is still the most important mahi to carry on.

Walking into Te Kohu at 21, that was a huge relief. I was still figuring out so much about myself, relationships and the meaning of life that adding Te Kohu on top of it all felt like trying to use a map to navigate my way out of fog; it didn’t work and maintenance was all I could really contribute to. So my role was comms — Facebook, Instagram and working with mates in media back here so that our mahi had consistent coverage, which ended up being really important because the timezone difference meant we were almost completely disconnected from the impact we were having back home.

While the haerenga has been a massive experience taking literally months to process, Waikeria mega-prison wasn’t built and the ara we travelled through remains open for more Māori to go on in the years ahead. Win.

4. It’s easy to take space, it’s harder to hold it.

I feel like this is a mic-drop whakaaro, or one where William Waiirua comes out of nowhere doing his waiirua hand thing and saying, ‘Hhhhhyeah that’s the hhhwone’. But in all seriousness, this learning has been long and continuous. My struggle with Te Kohu was witnessing the reality of that space — namely the corruption, lots of hui not much dui, broken promises, outright lies by governments and indigenous people being hurt. Every part of me was raging and it turned this into the ultimate wero because, as a creative, if something isn’t good mauri, my first response has always been to tap out. If I did that here though, I was taking up space rather than holding it and however hard, the space had to be held. Disengaging wasn’t as simple as catching the next waka at whaea Liberty back to Aotearoa; this was real and it was happening. Staying present in Te Kohu was the single most important thing to keep doing, because if it wasn’t for me to serve there, kai te pai, it was for someone to, and that accountability made the purpose behind choosing to continue holding space a lot clearer.

5. What is the whakapapa (origin) of my actions?

Adding another layer onto our kōrero about intergenerational thinking, this learning likens the actions of a person to how we understand whakapapa as connecting people from past to present and future. Instead of seeing action — feeling — whakaaro — intention — belief as unrelated to each other (pun intended), being in Te Kohu taught me to treat them as a whakapapa line where one affects all, and all affects one. Whether the tīpuna is a negative one like fear, insecurity, pride, or hate, or a positive one like aroha, manaakitanga or humility, the whakapapa expressions of that will simply be younger faces of the tīpuna. When you choose mahi over hauora; when you serve someone else’s kaupapa; when you let other people’s opinions of you hold more power than your own opinion of you; when you choose growth over that partner, friend, or whānau member; when you choose silence over speaking out; when you do whatever it is you do, what’s the whakapapa and who’s the tīpuna?

6. Pride in being Māori is a privilege.

Quiet Māori, staunch Māori, half-quarter-eighth Māori, white Māori, haati Māori, coffee-coloured skin Māori, plastic Māori, moko Māori, raised-on-the-pā Māori, book Māori, tūturu Māori, am I even Māori if I don’t know Te Reo Māori? I feel like you don’t really need to go into Te Kohu to understand this, but what going overseas does do is give this learning a far wider view than just Te Ao Māori. It was humbling to realise that where we start from is a far more privileged place on the ara than a lot of our indigenous whānau. Want to learn Te Reo? We actually have a language left to learn. Want to get into kapa haka? You can, our reo expressions outlived colonisation. Want to wear moko or piupiu? Also doable. We know what those look like, we have people who do that mahi and we don’t have to borrow another indigenous cultures’ appearances to reclaim being Māori; enough of our own lived on to be revitalised today.

And that’s not to discount the afflictions of our people at the hands of colonisation by any means — to belittle the pain caused by countless treaty breaches, brutal land grabs, the forced slavery of our tīpuna (which, p.s. if you didn’t know, Nelson, Otago and other South Island towns were built by Māori slaves), the bounties on Māori heads, acts passed through parliament like the Tohunga Act, the thousands upon thousands of Māori children abused in the state’s care and education systems — none of that. It’s to put into perspective that we’ve endured colonisation since the early 1800s, and others have been dealing with it since the 1500s or longer.

7. Connection to Papatūānuku, Tangaroa and Ranginui can be sparse.

The amount of stories on this one meeeeete you don’t even know. Struggle is real, let me tell you. A lot of times in Te Kohu, no matter where in the world the actual hui are held, there isn’t a lot of access to Papa or Tangaroa, and sometimes even Ranginui if you’re a city with tall buildings making him hard to connect to. As Māori, we often take our closeness to the environment for granted, but there’s nothing like being in a noisy city battling invisible taniwha within Te Kohu who are doing their pūkana at you every single day for three weeks straight with next to no access to wai, ngahere or the sky to make you feel like you’re going insane.

We had this one situation, I can’t remember how long we’d been there for, where we’d gone out of the actual wharenui to get lunch. On our way back, we saw this length of green grass with bushes, trees and low fences around it and a sign saying ‘NO CROSSING’. It must’ve been a hard day or the feelings of homesickness particularly strong cause all I could think about was sitting on that grass and gaining some sort of reconnection to Aotearoa. There was a guard post just a little way off so we walked over and asked the guards if we could have lunch on the grass. We explained we were from New Zealand and not used to being far away from grass, forests or oceans and they just looked at us like, seriously? Did you not read the sign? Needless to say they said no, and so we sat down in a space where we could at least see the grass, which was a step up from no grass at all.

It’s the little things nē. So if you go into Te Kohu, however and wherever you end up, take tāonga, a guitar, essential oils and diffuser, photos of whānau, your favourite kai (we took blocks of Whittakers chocolate and a 1kg bag of coffee beans) — anything that settles you because chances are, those things will have to take on grounding you in the same way we’ve come to expect from Papa, Tangaroa and Ranginui.

8. There is time. Use it.

I never realised how much time was in every single day until we were in Te Kohu working from 7–12 each day during the forum while adjusting to a 18 hour time difference with 9 other people in a whare where alone time was pretty much non-existent (feels for all the introverts). But there is so much time. Often I think it can feel like there isn’t cause we’re putting it into the wrong spaces, places and people, but even that’s a good lesson; if you’re not the rangatira of your time, other people will be. And if you’re doing things you’re not stoked to be doing, the amount of time you’re actually spending compared to how long it feels it’s taking can be pretty different.

9. We are a very young indigenous people — our raru (problems) and rongoā (medicine) are different to those whose wounds are older.

This one’s pretty embarrassing. Originally I had gone over thinking, very naively, ‘Yooo! Let’s look at the potential of taking Fruit from the Vine international in a few years!’ Lol cause I’m still trying to suss what doing this locally looks like auē *facepalms*. Anyway, my mistaken line of thought was, ‘let’s give to all indigenous peoples something that works for Māori!’ while at the same time having no grasp on the fact that many ruthless colonising extremes existed, causing many forms of mamae, to many indigenous peoples, over many hundreds of years. That has and never will be a simple, ‘one rongoā fixes all’ type situation.

How I realised the error in this whakaaro was from those hui before the forum started. The rangatira there shared the whakapapa of how Te Kohu came to settle on their whenua back in the 1920s and, as it so happens, there were two indigenous rangatira, Chief Deskaheh of the Haudenosaunee-Iroquois people and Tahu Pōtiki Wiremu Rātana who had started the mahi way back then. Setting the groundwork for the pathways that eventually came to carry thousands of indigenous peoples into the many hui being held within Te Kohu, they fought alongside others for our right to have space there back when it was called the League of Nations. So many closed-door decisions being made were affecting our tīpuna, but thanks to these two rangatira who started the mahi early on, that changed. Shout out to Rātana who, among his other mahi, helped give indigenous peoples around the world a voice in Te Kohu. Hearing that fact for the first time, I felt so proud to be Māori.

Learning the whakapapa of Te Kohu really put into perspective how young we are as iwi, as hapū, as whānau and as an indigenous people negotiating with a colonial government. It’s true, our raru and rongoā are different to those whose wounds are older, but just knowing this helps create a greater awareness of our place in Te Ao Mārama. What that means moving forward I don’t know, but I do believe this whakaaro is really important for informing where we are now and where we need place value moving towards.

10. Te kohu crucifies your indigeneity.

Let’s just be sure this last whakaaro is heard. Being an indigenous person in Te Kohu if you haven’t already guessed, is everything from incensing to crucifying, confusing, maddening, depressing, defeating and then back to incensing again. It’s hard. That’s by no means all it is, but it’s a large part of the experience and not something you easily forget, even after the mamae’s healed. I think that has a lot to do with not knowing it’s even possible, as a human being, to feel so much all at once, all the time, for so long. And we were only there for three weeks.

Diluting the emotionally intense reality of what you’ll likely feel in Te Kohu as an indigenous person isn’t manaakitanga. It just isn’t. But with nearly eight months having passed since returning to Aotearoa, what is important is that this kōrero comes from a place of genuine hope and optimism for the future. Being there brings out the cynic in everyone and the more realities you inhabit — indigenous, wxhine, takatāpui, religious, disabled, rangatahi, low socioeconomic background — the more times over you feel it. What I’ll be holding onto every time I journey back into Te Kohu is what I’ll end our kōrero with:

“To choose hope after kneeling at the feet of this world’s sorrow is one of the most powerful, painfully beautiful choices you can make. Every time choose hope, for what more can bitterness do that hate and greed haven’t done already?’

Ngā mihi for reading this e hoa. These learnings definitely aren’t everything — Hinekohurangi can descend as easily upon a ngahere (forest) as she can a plain and the experiences of one won’t necessarily be those of another. But these whakaaro are what I’ve carried with me; they’re the whenua I hold myself and my understandings of the world on now. I wish you every blessing in your journey forward, thank you for making time to read mine.

Ngā mihi,

Trinity